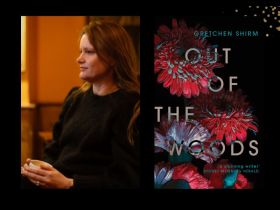

The best learning of Indigenous languages happens on Country. Image supplied.

Of the 120 Indigenous languages surviving today, nine in every ten is endangered. Fortunately this year provides a great opportunity to raise awareness, take actions to preserve and to celebrate our original languages with the UN General Assembly naming 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IY2019). And it’s not just about words.

The co-chair of the Steering Committee for IY2019, Craig Ritchie, sees the year as a step towards closing the gap. ‘We know in Australia that connecting with traditional languages has a positive impact on the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. So strengthening Indigenous languages will support happier and healthier communities,’ said Ritchie.

For other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, IY2019 means Indigenous languages can take centre stage.

Karina Lester, who works with the Mobile Language Team at Adelaide University, said: ‘It’s a huge celebration for the Indigenous languages of Australia that can bring awareness of the languages we have in our own backyard. The main thing is to really create awareness with our fellow Australians and to reach out internationally as well’.

The biggest challenge to the survival of languages is to ensure they passed down between generations. As Lester sees it, ‘The urgent stuff is really the languages that may have only a handful of speakers because they may never be heard again’.

Finding new ways for young people to get involved with Indigenous languages keeps them vital, such as through music and dance. Image supplied.

Passing languages between generations

In many communities elders are the keepers of language and lore. At the Noongar Language Centre in Western Australia, Denise Smith-Ali is working to revitalise the Nonngar Boodjar language. Initially this means gathering language from Elders from more than 14 clans, each with their own dialects.

‘Working with the Elders is about having a lot of patience and listening. We listen to their interpretation so the old people still have a voice and their voice is being listened,’ Smith-Ali said.

Because Australian Indigenous languages have close connection to the land, learning on Country is important.

‘You can’t separate language and Country,’ said Smith-Ali. ‘People are born with the knowledge of that tree, the name of that spear and where it comes from. They know their whole world in language.’

Indigenous language experiences are personal. As a man of the Dhunghutti and Biripi nations, Craig Ritchie didn’t engage with his Indigenous languages until he was in his fifties, but when he did, he experienced words meeting culture.

‘The effect it has had on my identity and sense of self is immense. It’s a joy to be able to speak to my grandkids in Dunghutti and know that they will not have to wait until they are 51 to connect with that part of our heritage and our culture,’ said Ritchie.

If you are involved even in a small way in preserving or promoting Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages, you can share your stories and be part of the celebrations.

You can also add your events to IY2019 calendar of activities by contacting us at IY2019@arts.gov.au.