Tarek Atoui was born in Beirut – a city with a bustling harbour life, and one that made global headlines in 2020. The year prior to that catastrophic explosion, Atoui, with collaborator field recorder Éric La Casa, captured the activity of its docks, hangars and silos. It was part of the ongoing project Waters’ Witness capturing the distinctive sounds of port cities, including Athens, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, Porto and Istanbul.

Sydney has joined that list. Waters’ Witness is currently showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), and is Atoui’s first exhibition in Australia. It presents three newly commissioned sculptures inspired by Sydney Harbour and Port Botany, where Atoui recorded sounds in March this year.

Atoui started his creative journey as a musician; however, he says the visual arts offered ‘more freedom than music’.

‘There was more space to explore another way of making music that felt more interesting and connected to what making music means to me.’

Speaking with ArtsHub, Atoui explains that, for him, ‘Sound can be made out of any material. And, therefore, when sculpting sound, it can manifest inside materials, inside matter, and not just in air.’

Curator of the exhibition, Anna Davis says she was especially fascinated by the way Atoui records through materials. ‘It’s not just putting the microphone out, like we usually do. It’s often using contact mics or underwater mics, and recording through solid objects or through the water.’

Davis says Atoui’s exhibition offers, ‘an interesting multilayered experience’. She explains: ‘The first thing that people might encounter is this sense of an archaeological scene in the space – chunky pieces of marble from Athens, big metal beams from Abu Dhabi laid out, and suspended platforms carrying sandstone from Sydney. So, in a visual sense, there’s this layering of objects, and then you encounter the sound in an atmospheric way.’

What does a city sound like?

Atoui believes that each city has its own sound DNA. ‘Sometimes it’s harder to recognise than in other places.’ He adds that you learn a lot about the place from listening to its harbours. ‘They act as a kind of resonator, not only of the sites, but the human flows and trade – about its concerns about its present.’

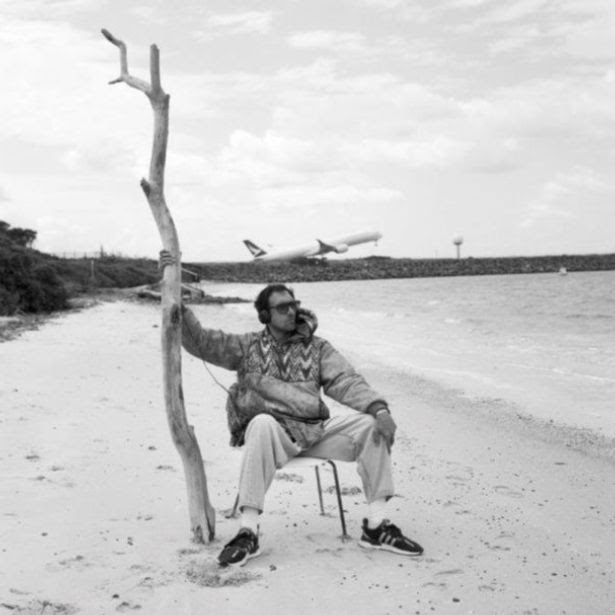

Coming to Sydney, Atoui was instantly drawn to how Sydney Harbour is in dialogue with the city, adding that he was especially drawn to that zone where natural reserves butt up against the industrial harbour and airport.

‘Sydney has this narrow geography, and coexistence of layers, which makes it quite complex.’ He adds that he ‘became sensitive to the history of this area where the Museum is. I think there’s more a connection between this work and the past of this place, than its present.’

Davis observes that while recording Sydney, Atoui became ‘obsessed with these perforated mesh pathways on the swampy edges of the coastline, which allow you to walk the shoreline, and are often cut around the rocks’.

‘It was a material that spoke to the ideas he was interested in, spanning these different realities between nature, society and industry,’ she says.

Atoui has utilised that material for the MCA’s installation, creating suspended terraces where the sandstone elements hover overhead.

While Atoui works with sound, the installation is more than an aural experience. The artist tells ArtsHub: ‘Listening does not happen exclusively with the ears. I would say at least three senses are active: aural, sight and touch. There is correlation between the elements you see, dripping, moving and the sound they generate. But there are other things where sight and hearing are not needed. You can sit on the elements and they act like speakers and you can feel the sound in the body – there’s a vibrational aspect of sound.’

He continues by describing a fourth sense engaged, ‘which is our sense of imagination, because sound is also evocative of feelings, of sensations, and is a trigger to thoughts and impressions that are very personal’.

Moving through the space visitors get that sense of layering, with sound coming up beneath them, overhead of them and reverberating through them. Davis adds: ‘In a way, you compose your own version of the piece by moving through it, in what you touch, what you listen to, and depending on the way that you experience the world.’

An instrument to be played

The final element to this dynamic installation is its performative aspect. Atoui performed over the opening weekend, and has invited local artists and composers to activate the installation across its duration. The next will be sound artist Gail Priest, on 24 November.

‘The idea of musicians from here working, not only with these sounds, but with all the other sounds within this composition, becomes interesting for me because it invites musicians to play in a way that maybe they haven’t done before, like playing the sandstone.’

He concludes: ‘It’s super important, like giving back the sounds to the city. This installation becomes at the service of the musicians who are plugging into it and performing with it.’

Even when Atoui is not performing there is a kinetic aspect to the work. Davis concludes: ‘Sound is emotional; it’s physical. It has all these different ways of affecting us. But I think it allows you to escape some of those more rigid ways of experiencing the world through vision. Coming into this space, there are sounds that you will hear that will be familiar, but they might be coming through unfamiliar objects. Then there are sounds that you will have no idea what they are, but they may affect you in a familiar emotional way. So just allowing that to wash over you will be quite an experience.’

Tarek Atoui: Waters’ Witness is showing in the Macgregor Gallery, Level 1, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA Australia) from 15 September 2023 through to 4 February 2024. It is accompanied by a program of events.

Entry is free.