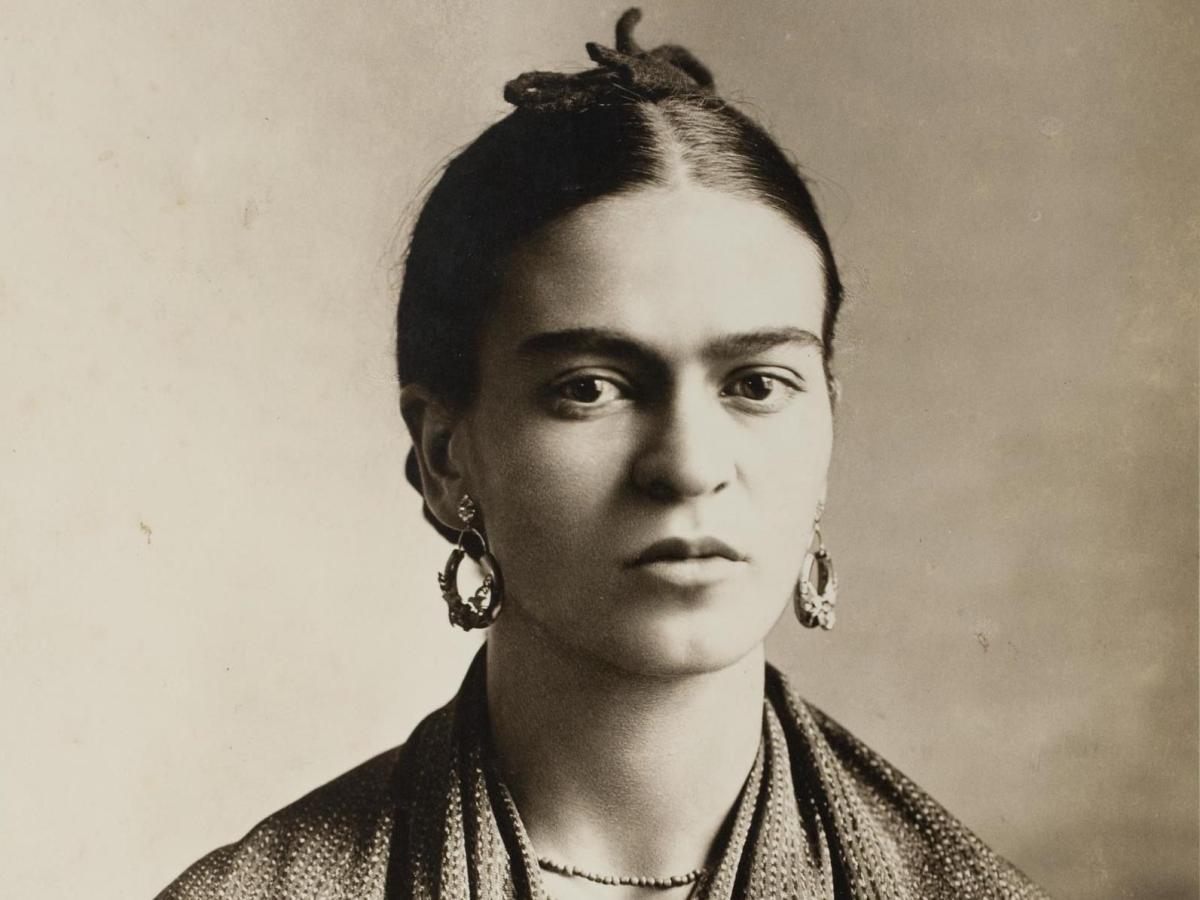

Image: Frida Kahlo by Guillermo Kahlo (detail), 1932 © Frida Kahlo Museum

At first glance, three current and upcoming exhibitions at Bendigo Art Gallery appear to have little that unites them.

Gothic Beauty: Victorian notions of love, loss and spirituality explores the Victorian era’s fascination with dark psychological narratives in life and fiction. It documents the influence of Queen Victoria’s adoption of perpetual mourning-wear on contemporaneous culture, and looks at the enduring impact of the Gothic today.

Daughters of the Sun celebrates the life and work of Australian Art Deco printmaker Christian Waller, examining her interests in Spiritualism and Egyptology, and her influence on the ceramic practice of her niece, Klytie Pate, who went on to become one of Australia’s foremost studio potters of the 20th century.

And Frida Kahlo, her photos provides a fresh perspective on the famous Mexican artist by turning her gaze outwards, away from her self-portraits towards her friends, family and the artistic circles she moved through.

But looking closer, we can see a common thread: all three exhibitions explore the considerable influence of these significant women, whether directly or indirectly, on the world around them.

In doing so, these exhibitions also speak to contemporary concerns, as well as the passions of Bendigo Art Gallery’s executive and curators.

‘The curatorial team here is all women; we are very interested in looking at and addressing the lack of representation of women in art. But it also just happens that this has coalesced in the moment where we’ve got this incredible suite of exhibitions looking at women from different periods, and the influence they’ve had on our society more generally,’ explained Curatorial Manager Tansy Curtin.

GOTHIC THEN AND NOW

Drawing inspiration from Horace Walpole’s landmark gothic novel The Castle of Otranto (published in 1764 and hugely popular among middle and upper-class women, who were drawn to the book’s potent blend of supernatural and romantic themes), Gothic Beauty traces the influence of the Gothic in art, literature and everyday life.

‘This idea of the Gothic often comes out at times of great fear and change, and there was a real fear of the modern when this popularity in the Gothic occurred [in the Victorian era]. People were afraid of industrialisation; they were afraid of this changing world. Because of course, at the time that Gothic novels started to emerge, that’s the period we also start to see the rise of the middle classes and a move away from the social systems that were well and truly established in Britain at that time,’ Curtin said.

She identifies similar disruptions today. ‘Just think about all the different shows on television, Gothic stories that have been remade, such as the new Sabrina on Netflix, which I watched recently. They’re quite dark, they’re looking at otherness, looking at that fear and trying to escape that fear. I think that’s quite interesting when you look at the world that we’re living in now, where there is quite a lot of fear – there’s fear of otherness, there’s fear of governments controlling what we read in the media … and I think all that helps creates that heightened sense of fear that we then put out through our arts and culture.’

Contemporary artists are certainly well represented in the exhibition, including Jane Burton, Michael Vale and Janet Beckhouse, whose works are shown alongside Pre Raphaelite paintings, a horse-drawn hearse from the 19th century, and mourning broaches featuring human hair – intimate mementoes of the deceased.

Installation view, Gothic Beauty: Victorian notions of love, loss and spirituality. Image supplied.

While the trend in mourning wear wasn’t started by Queen Victoria, it was certainly popularised by her in the decades after the death of her consort, Prince Albert. Rather than the customary two to four years, Queen Victoria wore mourning clothes permanently following Albert’s death, cementing the importance of such attire in society.

Given the rise of industrialisation and pollution, and the high mortality rates of the day – especially infant mortality – death was an everyday part of life for the Victorians, and Curtin believes we can still learn from their attitudes towards death today.

‘These people were continually surrounded by death. And so you have these rituals of mourning, which developed earlier but were really kind of cemented into society by the Victorians. They created rules and regulations around the idea of mourning – adopting a particular clothing style, this wonderful dedication to mourning jewellery, and all of those sorts of accoutrements,’ she said.

‘And really what that does is it tells the people around you that you’re in mourning – that you’re sorrowful, you’ve lost someone. You don’t have to have that difficult, awkward conversation with people – and we all know how terrible we are at those conversations – because you’ve got that immediate, outward sign that you are in mourning.

‘And obviously our lives have changed for the better – we have all these wonderful health systems, we have protection from terrible diseases through immunisation, the infant mortality rates are nothing like they were, but at the same time, death still impacts every one of us and we do need to talk about it; we do need to be having those conversations,’ Curtin told ArtsHub.

AN ARTISTIC INFLUENCE FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE

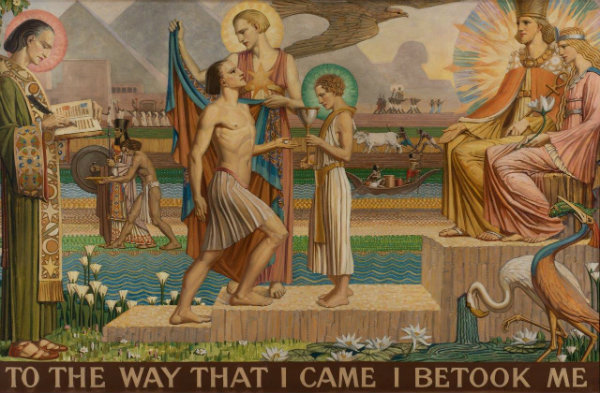

Born in Castlemaine and schooled in Bendigo, printmaker Christian Waller’s work – and her influence on the ceramics practice of her niece, Klytie Pate – which continued even after Waller’s death in 1954 – is celebrated in the exhibition Daughters of the Sun.

‘Christian Waller was interested in the ideas of Spiritualism and interested in Egyptology as well, and you can see those motifs throughout her work. And her work was absolutely influential upon her niece,’ said Curtin.

‘The early works that Klytie made, you can see that they were very much influenced by the Art Deco aesthetic of Christian Waller – those wonderful straight lines and patterning. But then you really see her come into her own when you see her beautiful glazed [ceramics] – “Klytie Blue” we like to call it – which is very typical of the later work that she made.

‘And you see her really claim this unique space in Australian studio pottery, which was so different from what the male artists were doing at the time. When you look at that period of “big brown pots”, as we like to call them … Klytie Pate’s work is very different from them, so it’s nice to see an Australian female studio potter working in a completely different vein.’

As well as exploring the pair’s intertwining lives and practices, the exhibition also questions Waller’s influence over her husband, stained glass artist Napier Waller.

‘There’s been some discussion over recent years about how much of the work Christian herself did and how much Napier did of their stained glass collaborations. So it’s kind of interesting to think of that side of her practice as well.’

Christian Waller, The robe of glory, 1937. Oil on canvas, 172.0 x 267.0 cm. Collection of the Greater Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust

CHANGING THE GAZE

This idea of re-examining established perspectives and traditional points of view is carried over into the exhibition Frida Kahlo, her photos, exclusive to Bendigo Art Gallery from 8 December.

Many will be familiar with Kahlo’s renowned self-portraits, a practice she began in her teenage years and continued throughout the rest of her life. Fewer people know that the Mexican Modernist was also fascinated by photography.

‘With someone like Frida Kahlo there’s almost a saturation of her look and her work within both the arts world but also more generally – she obviously has a huge appeal to young people, with those incredible self-portraits that she completed. But this adds a bit more to her personality, to our understanding of her,’ Curtin explained.

In turning the camera lens away from herself and onto the world around her, Kahlo’s photographs – and those she collected – also tell us more about Kahlo’s own world.

‘I think a lot of people don’t perhaps understand a great deal of what Mexico was like in that modern period, what Frida Kahlo was doing in terms of adopting Tijuanense and traditional Mexican costumes; the intellectual and the artistic elite that she surrounded herself with, and I guess the lifestyle more generally that she was living. So I think it’s quite interesting to reveal that through these – in many ways – very unassuming photographs.

‘They’re quite small, some of them she’s cut up and manipulated, and some of them are just really simple little contact prints – so none of these grand paintings that you expect from Frida Kahlo but still in lots of ways a very revealing portrait of her,’ Curtin said.

For Kahlo devotees, the exhibition will shed new light on the artist’s preoccupations and concerns.

‘Photography was such an important part of own practice – something that she used but she also collected. She amassed a huge archive of photographs. There’s some 260 works in this exhibition but that’s only a selection of the huge archive that is at the Casa Azul in Coyoacán.’

Frida Kahlo, her photos also tells us more about Kahlo as a person, Curtin concluded.

‘I think she was pretty hard on herself quite often in her own self-portraits. And obviously a lot of them are quite surreal and very much incorporating the key things in her life. But when we actually get to see her amongst her friends at the Casa Azul in Mexico City, you get a sense of her as a person, I think, a three-dimensionality, which is one of those great things about being able to see another side of an artist.’

Daughters of the Sun, Frida Kahlo, her photos and Gothic Beauty are showing at Bendigo Art Gallery until 10 February 2019. Visit www.bendigoartgallery.com.au for details.