Installation view of the exhibition, Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow at Queensland’s Gallery of Modern Art. Photo: ArtsHub.

At 88, Yayoi Kusama remains compelled to make art everyday. It is for this reason that the iconic Japanese artist did not personally make it to Brisbane for the opening of a survey exhibition of her work spanning some 70 years of her career.

But she will be everywhere. From urban posters to tote bags to social media, we will be flooded with the infectious appeal of Kusama’s branded dot installations and paintings, as well as her flaming red-fringed hairdo.

It is no surprise then, that even in her late 80s, Kusama continues to be ranked as one of the most recognisable contemporary artists of our times. Since opening in Brisbane, 37,923 people have visited the exhibition in last 10 days – testament to that appeal.

Read: GOMA trumps The Broad when it comes to experiencing Kusama

Here we take a look at GOMA’s exhibition and ask: has that brand been massaged globally too far in one direction? And what exactly lies behind this dot-obsessed granny?

The icon

Curated by Queensland’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) and the National Gallery Singapore, Life is the heart of a rainbow digs deep into Kusama’s early career to answer that question.

Walking into the first gallery, and surrounded by works from the early 1950s, co-curator of the exhibition Reuben Keehan told ArtsHub that the survey takes a look at how her work has been viewed in Japan, and doesn’t exclusively pull on the narratives constructed by Western art institutions and markets.

Keehan continues in the catalogue: ‘But why Kusama, why now? Certainly the centrality of installation in recent museum practice has played a role – audiences have shifted from viewers to physical participants in the work of art and variants of the problematic buzzword ‘immersion’ have become a fixture of the marketing lexicon.

‘But these factors do not fully account for the vastly complicated process by which non-Western, non-male artists achieve widespread acceptance, one compounded in Kusama’s case by her long-held status as a heretic.’

What is phenomenal about seeing these early pieces is the way they demonstrate the consistency of Kusama’s vision and iconic motifs. She owned and embraced the dot right from the outset.

An extensive timeline within the exhibition reveals that her obsession started as early as 1939 (when she was just ten), reproducing the net and dot motifs that she saw in her dreams and hallucinations.

Needless to say she had an unsettled childhood, and when Kusama returned to Japan in 1977 after living some years in New York, she voluntarily admitted herself permanently to a Tokyo psychiatric hospital.

Yayoi Kusama in front of Life is the Heart of a Rainbow (2017) ©YAYOI KUSAMA, Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore, Victoria Miro, London, David Zwirner, New York

Life and art blur

With time, the Infinity Nets grew in size to ever more complicated and expansive webs, and visitors are witness to this in the first room of paintings at GOMA. There are some killer works here that stopped me in my tracks, such as Infinity Nets (1952), a gouache with a tightly choreographed black line on a red field and Flower (1952), which has an uncanny connection with works made this past year and shown in the final gallery of the exhibition.

These works are incredibly rare, and given that Kusama destroyed thousands of her works before heading to New York in 1957, it is a great moment to have a number of them in Brisbane.

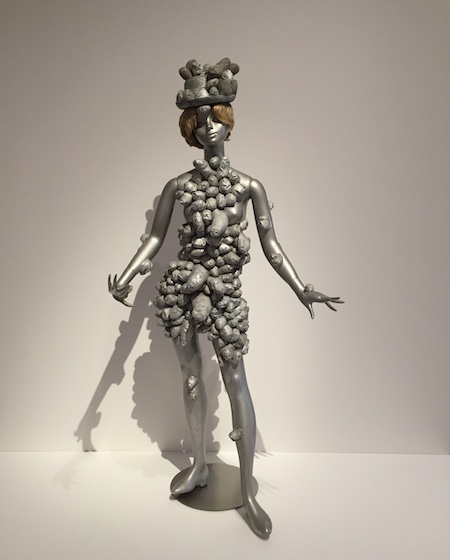

They are presented with the silver soft sculpture, Desire for Death (1975-76), placed centrally in the room with a Claus Oldenberg-meets-Andy Warhol feel, and the mannequin Phallic Girl (1967), which points to Kusama’s seamless crossover between painting and performance.

Kusama said of Phallic Girl: ‘I was trying to fight against males – it was like my own art therapy.’ She continued to make phallic sculptures until the early 1990s.

Installation view, Phallic Girl at GOMA.

This foundation to Kusama’s practice is explored in more detail in a side gallery with photographs of her Happenings (performances) in the 1960s and 70s in New York – a time of anti-Vietnam protests, freedom of expression, feminism and politics.

What a start! Another point of difference with these less circulated earlier works is that they are of different scale and slightly tighter energy than the more globally promoted works, two of which greet visitors: a pop-styled flower in steroid proportions in the gallery’s foyer, and five suspended acrylic yellow orbs with black dots in GOMA’s long gallery – the latter being a new work created this year.

From the outset we get a sense that there is a lot more to Kusama than that brand rolled out on social media. It was great to see an exhibition that was comfortable in being playful and popularist while also providing audiences with a little more depth.

Yayoi Kusama, The Spirits of the Pumpkins Descended Into the Heavens (2015) installation view at Queensland Gallery of Modern Art. Photograph: Natasha Harth. Collection of the Artist, © Yayoi Kusama

Signature yellow and black

It is not far into the exhibition that viewers are delivered those more recognisable hits that have made Kusama so famous – one of her immersive environments, and a suite of her pumpkin-inspired works pull the viewer into the next room. Works such as Sex Obsession (1992), Statue of Venus Obliterated by Infinity Nets No 2. (1998), and a later version of Kusama’s pivotal work, Mirror Room (Pumpkin) (1991) (the later version titled ‘The Spirits of the Pumpkins Descended Into the Heavens’, 2015), which was presented at the 1993 Venice Biennial.

After waiting in a short queue, you enter a yellow room totally covered in black dots; central is a glass box. Peering inside it, the viewer engages with an infinity field of small pumpkin sculptures reflected by mirrors.

Keehan writes that Kusama’s room installations are ‘about reaching out, about the intense involvement of the viewer inside her artworks’.

A fact I didn’t know – Kusama’s family owned a nursery growing up, so pumpkins were not only familiar but a major part of her diet. No wonder the obsession is ingrained.

A didactic panel in the exhibition reads: ‘For Kusama, the pumpkin represents comfort and security … [she] has said that their “generous unpretentiousness” and “solid spiritual balance” appeal to her. Its bulbous form suggests fertility, and each of Kusama’s pumpkins has a highly individual physical presence.’

Kusama made her first mirrored space in 1965, and they have a kind of hallucinatory repetition and expansion which has, in many ways, has become a trademark of her practice.

Also in this gallery was the soft sculpture installation, Death of a Nerve (1976), which I was delighted to see for the first time.

Installation view, Death of a Nerve (1976); Photo ArtsHub.

The exhibition takes a loose chronological path, but allows for plenty of space to find your own moments as a viewer.

Time adds a depth that is welcomed

What makes this exhibition different is that it is not just some buy-in blockbuster. Kusama’s work made its Australian debut at the Queensland Art Gallery with the 1989 exhibition, Japanese Ways, Western Means.

Then in 2002, Kusama’s practice was the subject of an in-depth focus within The 4th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT4), and in 2011-12 a solo exhibition of her new and recent work, Look Now, See Forever was presented at GOMA.

It is fair to also mention that three of the four large sculptural works in the exhibition have been acquired by QAGOMA over the years: the infinity mirror room Soul under the moon 2002, the large sculpture Flowers that bloom at midnight 2011, Narcissus Garden, and The Obliteration Room (2002-present), an interactive domestic space that viewers get to cover with colour polka dots.

I was lucky enough to view it with Keehan in its “all white” state. The sheer joy that people have in this space is impossible to criticise, a space largely filled with mums with babies and toddlers. The pram-parking bay outside the installation is a curious site, sculptural in form.

Narcissus Garden is also on display in QAG’s Watermall, and it’s great to see some early documentation of this piece in the exhibition. It first presented at the Venice Biennale in 1966, and is described by Keehan as her ‘best-known-art-word protest work’. Kusama wore a kimono and offered the 1,500 silver balls for sale for $US2 at Venice, a gesture in critique of the commercialization of the art world. She was expelled from the Biennale for her efforts.

Narcissus Garden (1966) Collection of the Artist ©YAYOI KUSAMA

The other big drawcard – Soul under the moon 2002 – is positioned with a separate entrance accessed from the long gallery, so that it doesn’t clutter or complicate the flow of audiences through the exhibition.

It is a smart move by GOMA and perhaps a more reasonable option than the concurrent American survey of Kusama’s work which is now touring, where visitors have been limited by a 30 second selfie rule and timed-entry to the exhibition.

Everlasting Beauty for the Never Ending, Universe (2016); Collection of the Artist ©YAYOI KUSAMA, Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore, Victoria Miro, London, David Zwirner, New York

Stronger than ever

I started this review mentioning that Kusama paints every day. She doesn’t employ assistants (other than to stretch her canvases), and she is prolific.

The last gallery in this exhibition is testament to that passion and cohesive vision across her seven decade career.

‘When Kusama began her epic painting series My Eternal Soul in 2009, she initially intended it to comprise 100 canvases. Still ongoing, the series of works in a riot of bright colours now includes more than 500 paintings, 24 of the very newest of which are featured in the exhibition,’ explained QAGOMA Director Chris Saines.

Arranged in a grid-like formation around the gallery walls, Kusama’s emphasis on repetition explodes with vibrant colour. They are presented with a group of works placed in the middle of the room that repeat the organic shapes and forms on the canvases (pictured top).

The word ‘eternal’ is key here – it is a remarkable reminder that, even at 88, Kusama is so incredibly strong in her making.

Keehan concludes in the catalogue: ‘As illustrated in the My Eternal Soul series, the richness of Kusama’s vision, and her unwavering commitment to articulating it, signal an underlying robustness to her creative output and offers rewards beyond the undeniable thrills of her larger-scale productions.’

And with Richter’s survey just meters away in an adjacent gallery, this is a moment of incredible contemporary art history that – for a visual artist or arts professional – it would be criminal to miss visiting.

Rating: 5 out of 5

Yayoi Kusama: Life is the heart of a Rainbow

Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Brisbane

4 November 2017 until 11 February 2018

Free

Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow has been co-curated by Reuben Keehan, Curator of Contemporary Asian Art, QAGOMA, with Russell Storer, Deputy Director (Curatorial and Collections) National Gallery Singapore and Adele Tan, Curator, National Gallery Singapore.