In 1992, the legendary American writer Kathy Acker said:

‘The students who come to my class are very closely related to all the evil girls who are very interested in their bodies and sex and pleasure.

‘I learn a lot from them,’ she revealed, ‘about how to have pleasure and how cool the female body is.’

Undoubtedly, the students who attended Acker’s classes at the San Francisco Art Institute were learning from her. They were learning from her radical openness to creating stories about sex, pornography, desire, pleasure, pain and violence – from a woman’s perspective.

When I visit The Body Electric at the National Gallery of Australia, I can feel Acker shadowing me. Her influence is ever present in a brilliantly curated exhibition by Shaune Lakin and Anne O’Hehir.

Two decades have passed since Acker’s death, but the eroticism she brought to art remains central to women artists.

Untitled (red Emily) (2017), by Claire Lambe. Image via the artist and Sarah Scouts Presents.

Women’s experiences of the erotic

The Body Electric features ground-breaking photography and video from the 1960s, 70s and 80s alongside more recent work from Australian and international artists.

Read More: Why we need to rehang our Australian art collections

It is an intelligent and daring visual exploration of women’s erotic experiences from the domestic to the pornographic.

Jo Ann Callis’ Untitled (nude with towel) (1976) portrays an anonymous woman seated on the long arm of a living room sofa, presumably using it to masturbate.

Nan Goldin’s photo series, The ballad of sexual dependency (1986), renders the traces of love’s violence. Its most powerful image, Nan one month after being battered (1984), is an honest self-portrait showing the wounds of physical assault by her then-lover.

Annie Sprinkle’s comically pornographic Pleasure Activist Playing Cards (1995) features porn stars posing as characters with wildly inventive names: ‘Horny Biker Shutterbug’, ‘The Mother Theresa of Female Ejaculation’.

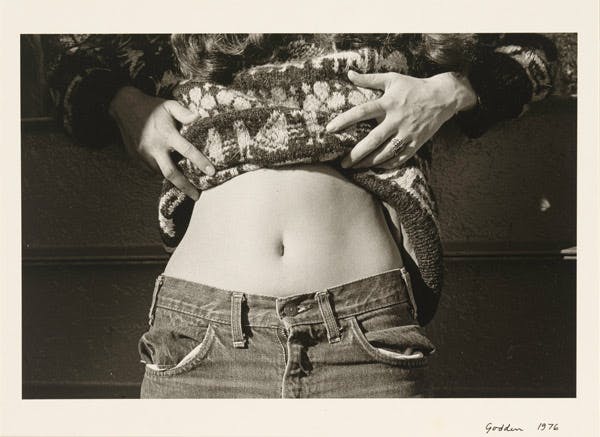

Self. Sunny day in winter (1974), by Christine Godden. Image via the NGA.

Christine Godden mischievously reveals her belly button in a humble black and white self-portrait titled Self. Sunny Day in Winter (1974). Collier Schorr’s Ass and leaf (2015), a simple but subversive image, reveals a backside with stretch marks.

Such bodily traces rarely appear on the airbrushed bodies dominating visual culture.

The more powerful works question the ways women and sexuality have historically been – and continue to be – represented from the perspective of white hetereosexual men.

Head (1993), by Cheryl Donegan, mimics a woman performing oral sex in heterosexual pornography. Donegan simulates the “money shot” (the pornographic trope of ejaculation, usually into the woman’s mouth) with a green plastic bottle spewing milk.

Directly alongside Head is Female sensibility (1973), a recording of the artist Lynda Benglis kissing her friend and colleague, Marilyn Lenkowsky. The camera captures the thrill of their touch. In close detail we see Benglis use her tongue to searchingly caress the inside of her friend’s mouth.

But the work is more complicated than a kissing performance between two women: their eyes are not focused on each other, but instead follow a moving camera.

The camera – and therefore the viewer – becomes proxy for the ‘male gaze’: the positioning of women in visual media as sexual objects for the visual pleasure of heterosexual men.

By being in control of the camera, in charge of her representation, and in charge of her pleasure, Benglis actively resists this male gaze.

Viewing Benglis and Donegan’s videos simultaneously side-by-side is mesmerising, their collective power amplifying the critique of the male gaze at the heart of the exhibition.

Some words are just between us from Experimental relationship (2010), by Pixie Liao. Image courtesy of the artist.

Evil girls

When Acker talked of the ‘evil girls’ who came to her class, she (like the artists in this exhibition) was rejoicing in them – while mocking outdated patriarchal standards that repress female representations of sexual pleasure.

The Body Electric visualises Acker’s legacy of the ‘female gaze’ in art: a female perspective of sex, desire and pleasure beyond patriarchal limits of passivity and reproduction. The artists in this exhibition position women as powerful creators, acutely conscious of their sexual agency as women and as artists.

People can find the body disturbing, especially when it is a woman’s body performing in ways that challenges social expectations of the private and the public.

But what of fake bodies? In the far corner of the exhibition is an iconic Cindy Sherman work Untitled #255 (1992), featuring a mannequin doll equipped with anatomically detailed sexual parts.

The doll is crouched on her knees with a ready and waiting plastic orifice. Her pose reminded me of an instructional video I once watched on how to give birth.

All our stories begin at the site of the female body.

Cherine Fahd, Director Photography, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.