The Tiwi Islands, which sit over the Clarence Strait, north of Darwin in the Northern Territory, have been of significant artistic and cultural interest to outsiders for centuries. They are also of major historical significance, being the site of the first, unsuccessful, British settlement in the Northern Territory.

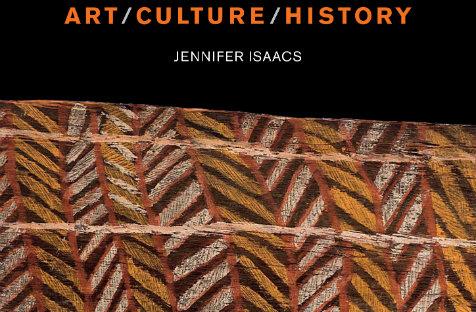

Previously written on by Charles Mountford, the anthropologist and author of a rare comprehensive volume on Tiwi art, the Tiwi have, until now, had no encyclopaedic work documenting their art and culture, particularly their contemporary art movement. Jennifer Isaacs’ TIWI Art / History / Culture is thus the first book to do so.

Mountford began his 1958 study by noting a fact few Australians would know: that Melville Island (which along with Bathurst Island creates the Tiwi Islands) is the second largest island, after Tasmania, in Australia. His attention to recording the detail inherent in each Tiwi painting: where every line is symbolic of geography, totemic animals or spirits, and mythology, is still significant in the undertaking of an appreciation of Tiwi art, whose admirable focus on design (the Tiwi word jilamara, also the name of one of their art centres, means the concept and theory of good design; it is a word the English language lacks) can mask the depth of information depicted in their art.

Most of us are familiar with the striking Tiwi Pukumani poles held on permanent display in the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Collected by the Assistant Director of the gallery, curator and artist Tony Tuckson, they were Australia ‘s first installation of Indigenous art in a fine art context, rather than an ethnographic one (although, as Isaacs notes, they were relegated to the lower level of the gallery until 2009 when they were finally given their due position on the ground floor). They also influenced Tuckson’s painting significantly, through which he created a unique Australian abstract-expressionistic language.

Many would also be familiar with the famous artist Kitty Kantilla, the only Tiwi artist to have been recognised with a retrospective in an Australian public gallery. Her 2007 retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria still counts as one of the most significant exhibitions of Australian Indigenous art to date. Kantilla ‘s sublime prints, the result of a pioneering art project by the Australian Print Workshop ‘s Martin King, are some of the most notable exercises in mark-making through etching created in this country. Kantilla was one of the most collectable artists of her time, with a minimum three year waiting list for her works. Her art was fundamentally Tiwi.

There can therefore be no debate that TIWI Art / History / Culture is a much-needed book on a major art genre, the ‘first complete volume to bring together the strands of Tiwi history and cultural expression and provide the context for contemporary Tiwi art’. It is a monumental feat of impressive long-term dedication to the research and study of one of the world’s most fascinating cultures. Isaacs, a well-known Australian author and curator specialising in Indigenous art and culture, has over 40 years history of visiting and studying the Tiwi, and the book is a product of this, as well as years spent in writing.

It begins with an introduction by the well-known younger generation contemporary Tiwi artist, Pedro Wonaeamirri, who immediately makes clear the significance of the uniqueness of Tiwi culture, and its difference from that of mainland Aboriginal people.

Isaacs then begins with a summarising introduction, discussing the turbulence of the past decade for Australia ‘s Indigenous communities, the Tiwi amongst them. It sets the tone for a text that doesn’t shy away from the complex history of these people. Fiercely independent, the Tiwi have resisted invaders, from the Dutch to the Japanese and British, for centuries. And yet even they are finally becoming overwhelmed by the relentless tide of cultural devastation. Isaacs notes with some sadness that contemporary Tiwi artists, when ‘looking at images of great old works’ will ‘too often say ‘no more’ or, more poetically, ‘we living in future now’.

‘The ceremonies remain,’ she notes, ‘but have subsided.’ But if they are no longer practiced, Isaacs continues, ‘how the young can acquire knowledge of the customs and laws will become a new question for the new schools to consider, just as much as it is for the parents and grandparents.’

The introduction covers the major, yet disparate, subjects of Tiwi culture: the land councils, the artists and collectors, such as Margaret Preston, who have had historical fascination with these islands, and the development of the contemporary Tiwi art industry, which is hugely significant: there are five art centres on these islands, as well as a pottery, and it was Tiwi artist Timothy Cook who won the most esteemed award in Aboriginal art, the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, in 2012. The introduction concludes with the future, then the author begins the book’s main body.

This consists of five major parts: Tiwi Culture, History, Artefacts and Art, then the Bathurst and Melville Island Art Centres respectively. Within these, we find many sub-sections: the early visitors to the islands, the missions, the early collectors and curators, the pioneer carvers and painters, major collectors of the mid to late 20th century, the creation and development of fabric printing, printmaking, ceramics, sculpture and painting. The Tiwi painting movement’s artistic and spiritual strength is expressed by some wonderful quotes from the artists themselves in the biographical section, with which the author concludes. ‘I will take a painting to heaven so my mother will recognise me,’ says Timothy Cook, while Jock Puatjimi simply and eloquently states: ‘Painting is prayer for Tiwi people.’

Many remarkable images illustrate the text, including those by Walter Baldwin Spencer, scholar, anthropologist, Chief Protector of Aborigines and photographer. His images – of the old Tiwi men, painted for ceremony, graphic decorative cicatrices adorning their bodies; the groups of Pukumani poles, such beautiful, sophisticated tribal grave-post art installations, with Tiwi men sitting in front of them; the remarkable bark huts, the later conical examples which are described in a quote here by journalist Colin Simpson as ‘having been designed by someone who had read a what to do in the wilderness manual’ – even today these are striking and powerful.

Further striking photography of Tiwi culture by Axel Poignant, Herbert Basedow, Ted Ryko, Hermann Klaatsch, Tom Nell and Peter Eve, as well as extensive use of archives, are used to great effect. Curiously, no images by the contemporary photographer Heide Smith, who photographed the Tiwi over a 20 year period, appear. The ground-breaking former curator of Indigenous art at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), Margie West, is one of the visitors to the islands whose images feature throughout the book.

Isaacs educates us in fundamental Tiwi knowledge: the creation stories, how death came into being. She follows with an entire chapter on Tiwi Ceremonies, the source of much contemporary art. The book manages to successfully weave together all the complex strands of Tiwi artistic history, and organise it in such a fashion that one cannot help but be impressed and enthralled. What is also notable about this text is the brilliance of its writing: it is written informatively and engagingly, and is full of interesting, wonderful pieces of rare information. Isaacs’ account of the collector of Tiwi art, Sandra Le Brun Holmes, is one example. She writes how Holmes had come to Darwin with her husband, the filmmaker Cecil Holmes, who was appointed editor of the Territorian newspaper, and ended up becoming so intrigued by Tiwi culture she became an anthropological recorder for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS, now AIATSIS), developing deep friendships with Tiwi artists, and transforming her house in Darwin into an informal museum. When Cyclone Tracy hit, the house was destroyed, but, incredibly, eerily, even ‘magically’, as Isaacs writes, the art survived, and now forms a cogent part of the MAGNT Indigenous art collection.

Isaacs’ attention to the stories of the collectors is valid, as it was largely they who led the way with regard to the validation of Tiwi art as fine art. With the exception of Tuckson and the collecting interest of Frank Norton, the director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Isaacs notes, ‘the major Australian art institutions were still reserved in their appreciation of Tiwi art as ‘art’ or in accepting that Indigenous art should be collected by art institutions rather than ethnographic museums.’

Most importantly, this large format hard-cover is a great art book. It is filled with stunning images of the quite extraordinary range of Tiwi art. The images throughout are often captioned with fascinating details, unfortunately in quite small font. It is a shame there is such a flaw in the book’s design, which is otherwise adequate and clear, as much care, research and attention to detail are present in the captions. An image of the hand-painted illustrations of painted Pukumani poles by Herbert Basedow, in the first published study of Tiwi culture, for example, argues a major point: that the ‘vibrant colours and strong designs of Tiwi art were to become important in the drive to create a visual identity for Australian artists and designers.’ Yet I fear many readers will skip over these captions, not bothering or simply unable to read them because of their small type size.

Yet, overall, TIWI Art / History / Culture is a major contribution to art history and a requisite volume for any Australian art library, as well as being a beautiful book. Anyone interested in Indigenous art, Australian art, or the history of Australia will benefit thoroughly from it. Above all it is a testament to the vibrant art and culture of such a wonderful people, and will become a cherished document for them and their future generations.

Rating: 4 ½ stars out of 5

TIWI Art / History / Culture

By Jennifer Isaacs

Hardback, 327pp, RRP $119.99

ISBN: 9780522858556

Miegunyah Press