This Melbourne Shakespeare Company production of Hamlet, Shakespeare’s famous tragedy – and longest play – at Melbourne’s fortyfivedownstairs has been distilled to a (still sizable, but eminently watchable) two hours and 50 minutes (including interval). The cuts include a sensible removal of the arrival of Fortinbras (King of Norway) at the end, so the play ends at the (much more dramatic) death of all the characters. Despite the many strengths of the production, its ending is disappointing.

Set in the round with four seating banks facing each other, the stage is intimate, contained between four structural steel beams of the theatre – a smart use of the architecture that evokes columns: an appropriate juxtaposition of the classic and contemporary.

In this confined theatrical space, we see the actors’ spit flying, we feel the threads of tension push and pull as each body moves across the space, eddying the air, as others shift to recalibrate. Characters emerge from the audience, allowing them to energetically contribute to the scene as a sort of court chorus, and connecting the audience to the play as the extension of the court.

The production is unselfconsciously and sensibly modern, helping to keep the focus on the drama, action and universally juicy existential and psychological themes of the play. Hand-held mobile phone torches are used in the opening (and subsequent) night-time scenes to light up characters, to search for the source of the unholy sounds rattling and clanking in the night. Drawing long shadows and creating a sense of terror and tension, Hamlet, Horatio and the guards jump at ghosts – whether real or imagined.

As an audience we don’t see the ghost of Hamlet’s father at first – and it’s only when Horatio tells Hamlet that the ghost has been spotted at night by the guards that Hamlet (and the audience) begins to see him. From the beginning, therefore, it seems that Hamlet’s father’s ghost is all in his head: that the guards’ imagination is enough to give fuel to the fire of Hamlet’s budding grief-stricken madness, which then consumes him throughout the play.

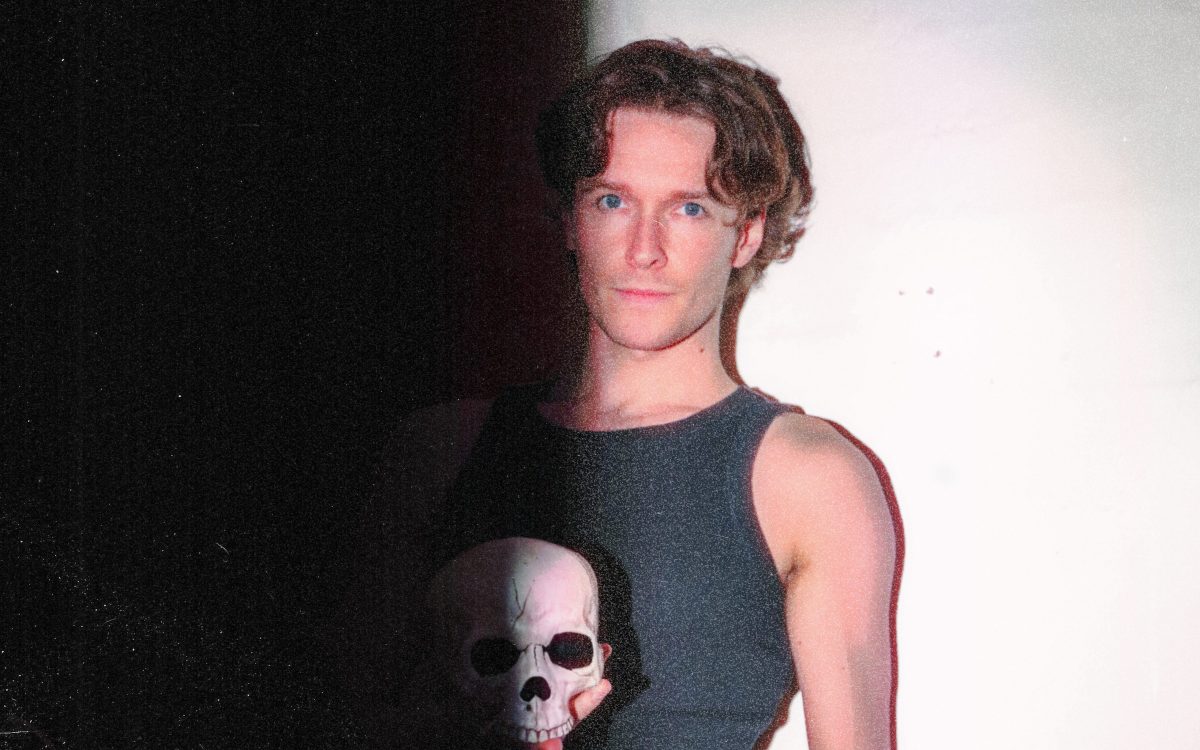

Costumes reflect the status of the characters: Laertes in cream cable knit jumper, Queen Gertrude in a luxe royal blue satin shirt, King Claudius and his adviser Polonius (Laertes and Ophelia’s father) in suits. Floppy-haired Prince Hamlet is in black jeans, black tee, black Docs and long black overcoat – channelling a first-year philosophy student who has just discovered Nietzsche and The Smiths. But this performance by Jacob Colins-Levy is no one-note wonder. The grief is there, the rage, the bouts of melancholy and the desire to avenge his father’s murder – as is the see-sawing between the crippling indecision, that is the source of his tragedy, and fits of light-tongued merriment.

An experienced cast has been assembled by director Iain Sinclair – all making the language feel fresh and alive, in natural accents. Natasha Herbert (who played Mark Antony in Melbourne Shakespeare’s production of Julius Caesar earlier in the year) plays Gertrude – a pragmatic survivor, who has remarried brother-in-law Claudius on the death of her husband, King Hamlet. But despite young Prince Hamlet’s rage at his mother (‘frailty, thy name is woman’), Gertrude’s motherly protection for Hamlet is conveyed in tiny moments – the gently quelling lift of a hand when Claudius refers to Hamlet’s continued mourning of his father as ‘unmanly grief’, which helps us see Hamlet’s tragedy as partly a problem of masculinity. Bereft of his hero-figure father, and suspicious of his usurping uncle, for Hamlet, supportive male role models are in short supply.

A few questionable directorial choices let the play down – in particular the final scene in which Hamlet’s death is followed by the recently deceased Ophelia returning to stage, before the pair reunite with a joyous kiss and leave the stage hand-in-hand to join other spectral characters gathered around a candlelit table. The choice feels deeply at odds with Hamlet’s inherent tragedy, serving to effectively change the end of the play and provide a happily-ever-afterlife for the characters.

Hamlet is not a romance and certainly not a necromance, so this directorial decision jars. Aisha Aidara’s Ophelia is the essence of youthful vulnerability and her descent into suicidal madness is appropriately horrifying – do we really need to see her pash her abuser postmortem?

Another choice of staging the fencing battle between Hamlet and Laertes offstage – perhaps necessitated by the small stage area – sadly pulls all the stuffing from the climax of the play.

Read: Theatre Review: Iphigenia in Splott, Red Stitch Actors’ Theatre

Despite these (hard to ignore) problems, the production overall is a lively and modern interpretation of Hamlet, featuring excellent performances throughout. If they’d only just stick a bodkin in that ending.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

fortyfivedownstairs

Melbourne Shakespeare Company

Director: Iain Sinclair

Producer: Jennifer Sarah Dean

Stage Manager: Jessica Smart

Marketing Coordinator: Bridie Pamment

Sound Designer: Grace Ferguson

Lighting Designer: Natalia Velasco Moreno

Set and Costume Designer: Tait Adams

Fight Coordinator: Joshua Bell

Assistant Director: Marni Mount

Assistant Stage Manager: Frankie Lupton

Cast: Aisha Aidara, Ben Walter, Christopher Stollery, Darcy Kent, Darren Gilshenan, Dulcie Smart, Emmanuelle Mattana, Gareth Reeves, Gispa Walstab, Jacob Collins-Levy, Laurence Boxhall, Natasha Herbert, Orion Carey-Clark, Peter Houghton, Simon Maiden, Terry Yeboah

Hamlet will be performed until 22 September 2024.