Installation view Brook Andrew solo exhibition at NGV Australia; Photo ArtsHub

The Right to Offend is Sacred – it’s a great title, but what does it mean for artist Brook Andrew? And furthermore, ‘sacred’ for whom? These are the challenges Andrew throws out like a hook-on-a-line in his solo exhibition at NGV Australia.

Over his 25-year practice the art world has become familiar with Andrew’s particular brand of making that combines the archives with a blur of contemporary materials – from photography to video, neon, text and collage, to assemblage and installation. He takes up the role of interrogator, where racial stereotypes, colonial histories and modernists frames sit firmly within his gaze for dissection.

There is no mistaking his visual language. It has a graphic flair that is not afraid of scale and is spatially curious. It invites the viewer to dip deep, but then pops that conversation into high volume – almost hi viz.

That tale is delivered by over 100 works in this exhibition which Andrew is adamant is not a survey, but rather ‘a museum intervention’.

What does that look like – feel like – for the visitor?

Political tension versus physical tension

Two new large-scale sculptures sit outside the exhibition space that has been turned over to Andrew’s show, feeling somewhat disconnected from the other works. They are impeccably crafted bespoke wooden cabinets, dense with material and reference. It is a clue for what lies ahead, but that full understanding is only apparent on exiting the show.

What catches one’s eye rather is a neon work emblazoning the doorway with the text, Kill Primitivism in shocking pink. It heralds the viewer’s entry into what I would describe as an archival intervention – a darkened room containing years of collected materials that the artist re-presents in a deliberate shoulder-rubbing conversation in vitrines.

It is dark. One reads the work by the glow of a neon line that runs above head-height around the room. Framed images are hung top aligned to the neon – one ponders whether this is a symbolic “toeing of the line” of histories rhetoric?

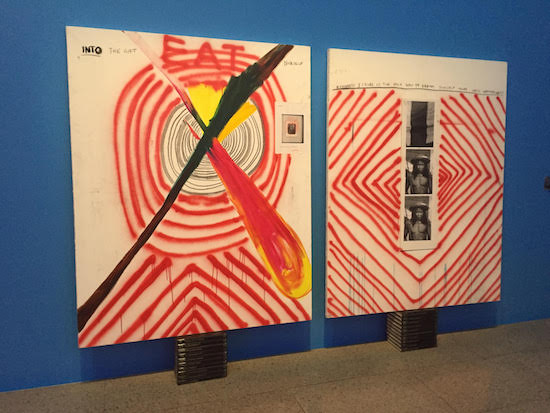

Installation view Brook Andrew solo exhibition at NGV Australia; Photo ArtsHub

Among them is the title work the right to offend is sacred, which was lifted from a headline in The New York Times from around 2008. Andrew explained of his manipulation of the headline: ‘It’s pasted over a full-on Baroque interior, so there’s a lot of humor but for me it’s about the velocity of dominant cultures, the velocity of opinion, and hence reflects the outside voices of “You shouldn’t’ do this and you should do that”.’

As a Wiradjuri man, it has particular resonance with the many conversations around how we discuss Aboriginality.

First impressions are layered. There is so much to digest. One wants to dwell and read but is also conscious of time and moving forward. It is an interesting curatorial decision to put this volume of material first. Most basically, it underscores the role of the archive across Andrew’s career as his foremost preoccupation.

Installation view Brook Andrew solo exhibition at NGV Australia; Photo ArtsHub

Walking into the second gallery the visitor is almost assaulted with visual overload. A tri-channel video work hovers (and encroaches) over one’s shoulder; deliberately darkened archival ethnographic portraits sit on easels lined up in a regimented formation with his Gun-metal Grey series (2007), and the sculptural work Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013) beckons interest, like a giant megaphone shouting out a message of ethnographic genocide.

It’s wunderkammer configuration plays off a European fascination with the ‘primitive’; the skull in this work referencing an ‘unexplained’ specimen simply labeled ‘New South Wales’ in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, UK.

Andrew says in the exhibition’s catalogue: ‘It’s not even political, it’s historical isn’t it?’

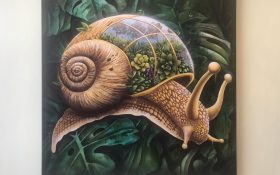

Moving deeper into the exhibition, the next gallery is dominated by a new inflatable globe sporting Andrew’s iconic black and white striped motif. A pair of canvases The Gift (2016) and Remnants (2016), sit on tomes of history, and echoing the same stripe motif. It is art that has a global feel to it – cognisant of contemporary art vernacular – and yet this is a very personal, and local narrative.

Installation view Brook Andrew The Gift and Remnants at NGV Australia; Photo ArtsHub

And at the end of the gallery a glass coffin lays (In the Mind of Others, 2015) before a suite of portraits of First Nations Peoples. The walls ricochet the motif, not like dazzle camouflage popular in World War I – its intention was not to conceal but to make it difficult to estimate a target’s range, speed and heading.

They sit almost as constellations within a sea of history, clusters dense with reference and visually dense as objects.

At this point as a viewer you are staring to question the logic at play in this hang. The role navigation is clearly key – your are funneled and pummeled, spaces open up and contract; it feels congested and then quietly contemplative, you are forced to crane your neck and look up and then to drill down in a cabinet. The micro / macro pull is intense.

On top of all this stimuli, Andrew pumps up the intensity further by painting the galleries walls as one might a geometric painting. Again, it works against convention in organising the space – the hang seemingly breaks all curatorial rules (whatever they may be).

Part of that adds a spatial excitement to the exhibition, and yet it is very demanding on the viewer to take that physical journey and open themselves to its responses.

Andrew has been described as ‘willfully provocative’ and both a ‘social critic and a storyteller’. I would have to agree.

Installation view Brook Andrew solo exhibition at NGV Australia; Photo ArtsHub

This exhibition is about alternative ways of displaying history and encouraging the viewer to rethink their own structures of understanding, ‘to retrain their gaze’, as curator of the exhibition Judith Ryan described.

Andrew added in the catalogue: ‘I have come to the point where I prefer to work on subjects that are more condensed and intense.’

It is almost like he is auditing history, with the same level to miniscule detail and critic consideration of that profession.

Andrew describes is as a kind of meditation for him, constantly mining different material to force an interrogation rather than merely unearth another copy of history told.

There is herocism across this exhibition. There is also darkness in the shadows of its neon glare. It is seductive by its very energy in the space, and yet it leaves the viewers on an unresolved high. You have been pushed to think different, but you have not quite found the answers.

For that very reason this exhibition in my definition is kick. It answers the demands of today’s gallery going audiences hungry for engagement, and yet, it is an incredibly erudite dance that extends that viewer into new understanding.

And on top of that, Andrew is a superb technician. The work is beautifully fabricated and resolved as individual objects.

This is undoubtedly important work, and needs to be experienced in the flesh.

Rating: 5 out of 5

Brook Andrew: The Right to Offend is Sacred

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

Federation Square, Melbourne VIC

3 March – 4 June 2017

Programs associated with the exhibition:

Panel Discussion: The Importance of Remembering, Thursday, 20 April, 6.30pm

How do artists respond to history and archives to create new memories? Guest panellists discuss the different ways artists around the world interpret remembering to commemorate histories.

Floor Talk: Curator’s Perspective, Saturday 21 May, 11am