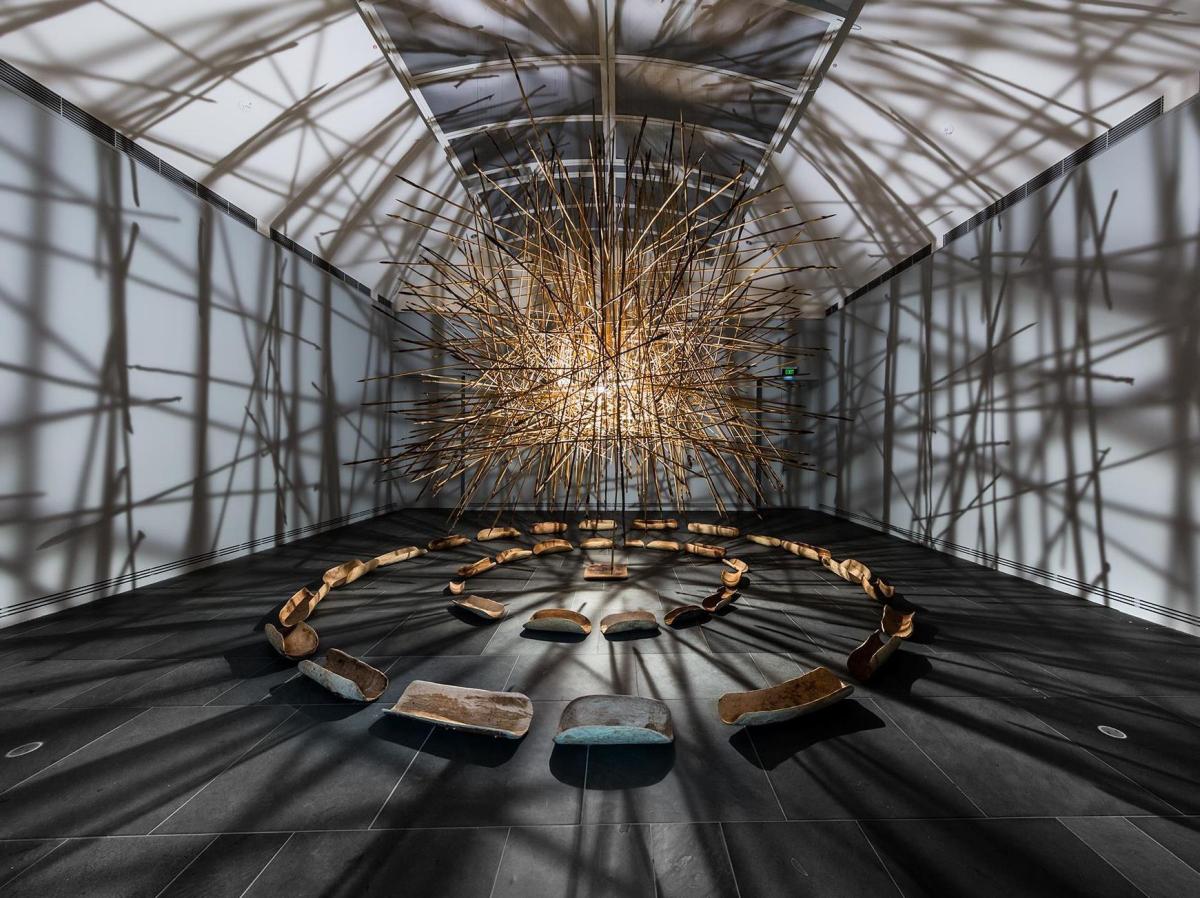

Installation view, 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, featuring Kulata Tjuta, Art Gallery of South Australia; Photo credit: Saul Steed.

How do you review a festival? It can be an impossible task given the scale of activities and their overarching ambitions – offset against the subtle nuances of individual projects within that fray.

TARNANTHI is no exception, with 24 projects and over 300 associated events over a 10-day period, attracting more than 75,000 people. The numbers were 50% up on the inaugural event in 2015, which is testament to the festival’s success. But how did it feel on the ground?

The core exhibition

While the big splash festival has wrapped up, several of the exhibitions continue through to January next year. Core to TARNANTHI is the Art Gallery of South Australia’s (AGSA) – shall we call it “the keynote exhibition”? – the one making the big statement and laying the legacy pathway.

It presented over 40 new commissions, and yet managed to avoid that art-overload feeling, being a well paced and spaced exhibition. Behind the exhibition’s huge team is curator Nici Cumpston, whose name has become synonymous with this event and its success.

The highlight at AGSA was the much photographed, much celebrated Kulata Tjuta (Many Spears) installation (pictured top), featuring over 550 spears made by men across the APY Lands, and coordinated by that region’s tight network of art centres. It beautifully bridges the passing on of traditional knowledge and contemporary art vernacular and presentation.

Kulata Tjuta (Many Spears) continues a project inaugurated with the first edition of TARNANTHI, but has taken it to a new level. The spears seemingly levitate in a softly lit space forming an explosive cloud, and therein speaking of atomic bomb testing upon Anangu Lands – a story still very real to many of the men who made these spears.

Below it are hand-carved piti (wooden bowls) made by 24 Anangu women. The pairing is very special; it is really the ”stuff of goose bumps”.

This is exactly the kind of work we expect of biennales and festivals – big impact, big story, big engagement works that have that much-desired “stickability” – that is, at the end of one’s festival feast it is this story that lingers and is remembered.

The installation was presented in an upstairs gallery at AGSA, with adjacent galleries showing a collection of paintings from APY Land artists working out of the centres Tjala Arts, Mimili Maku Arts, Iwantja Arts and Kaltjitit Arts; photographs of contemporary rock drawings in the project Tjungu Palya: Painting on Country, and usurped Australia Post mail bags that tell a story of land rights by Mumu Mike Williams.

Keith Stevens describes those rock drawings, which in many ways captures the ethos of TARNANTHI: ‘Whitefellas are seeing all our work on canvas but we want people to see the places that really are this Dreaming. Then you will see how much we love our Country and why we always want to stay here.’

While displayed in a somewhat awkward space, the photographs of Stevens and fellow artists really sing to the kinds of bridges that TARNANTHI offers to viewing audiences, and the capacity that commissioning new projects has in sustaining tradition.

Another room pulls together woven works by Shirley Macnamara, sculptures by Jimmy Pompey and Eric Kunmanara Barney, and the naïve style “cowboy” paintings of Nyaparus William Gardiner. I am not entirely sure whether the line up of those first rooms was seamless; their conversations felt a little discombobulated. But then that is the nature of a survey exhibition.

Installation view 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art; Photo Saud Steed

Downstairs however, the galleries came together beautifully. Descending the stairs the visitor encounters three works: the distinctive black and white Mokuy (spirit sculptures) (2017) by Nawurapu Wunugmurra from Arnhem Land, featuring the Yirritja moiety triangular design for clouds (wangupinin); a video installation with bone containers/burial poles by Nonggirrnga Marawilin of the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre paired with the two-channel projection Lightning; and a stunning suite of Yolngu barks by Nonggirrnga Marawilli.

Installation view 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, featuring Pepai Jangala Carroll, Vincent Namatjira, Derek Jungarrayi Thompson and Shane Pickett, Art Gallery of South Australia; Photo Saul Steed

One then moves into a room with Vincent Namatija’s paintings Gina, Donald, Malcolm Obama and Me – contemporary decision makers over Country – with Pepai Jengala Carroll’s stunning pairing of paintings and ceramics from Ernabella Arts, telling the story of revisiting Country from his childhood; ceramics by Derek Jungarrayi Thompson, paintings by Shane Pickett, and of particular note, Andy Snelgar’s contemporary carved spears, boomerangs and clubs.

This room just sings; it’s beautifully curated and weaves stories of Country past and present.

Photography has been used across this exhibition, taking an ethnographic documentary genre but empowering it by owning those images – rather than being the subject of them as “other”.

We are introduced to Rickey Maynard’s 2015 series of Tasmanian Aboriginal men in a side gallery, which causes us to consider their societal role today, and later in the exhibition are Robert Fielding’s Mayatja Pulka: The Elders, accompanying major collaborative APY Land paintings.

Installation view 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, featuring Robert Punnagka Fielding and Taylor Wanyima Cooper, Art Gallery of South Australia; Photo Saul Steed

The exhibition moves between painting and object making with the kind of synergy and energy that we find at play in these art centres – they are perhaps less specialised than we imagine.

Among one of the great clusters in the exhibition is a stunning suite of paintings from the Jirrawun Collection from the Kimberley Region, by artists such as Freddie Timms, Rammey Ramsey, Goody Lilwayi Barrett and Phyllis Thomas. The scale and subtly of these paintings is impressive.

Installation view 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, featuring Jirrawun Collection, Art Gallery of South Australia; photo Saud Steed

The central gallery also does a great job in making sense of the disparate works of Reko Rennie – a three-channel video where he literally does circle work on Country in a custom painted Rolls Royce – and the Hermannsburg school project, What if this photograph is by Albert Namatjira? Here, photographs from the South Australian Museum’s Rex Battarbee Collection, which document Namatijira and his Country, are recreated as paintings by artists who continue Namatjira’s legacy today.

As these works were unveiled at the festival’s opening weekend, news broke that the long battle over the copyright to Namatijira’s works had been won.

Read: The $1 Namatjira Copyright deal – how it happened

Another highlight at TARNANTHI were the two enormous collaborative paintings by APY Elders – one a women’s painting of the Seven Sisters story, and another by the men, which was painted in the memory of Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, who passed in the early days of painting this work. They are magnetic.

Installation view 2017 TARNANTHI: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, featuring APY Women’s Collaborative and APY Men’s Collaborative, Art Gallery of South Australia; Photo Saul Steed

And for this writer, Dean Cross’ series PolyAustralis was another win in the exhibition, again turning to photographs as source material via a found book of eminent Australians – none of whom were Indigenous. Almost like redacted documents, he works back over the images with black ink, then prints them so that the two versions of history become fused as one.

‘Cross’s investigations into the possibilities of abstract mark making is intended to obscure the printed text and expose or reveal elements of identity in the portraits’, writes Janelle Evans in the catalogue.

Overall, the exhibition’s scale is digestable; you can walk away feeling that you have a strong grasp of an artists’ work and there is a resounding casualness that is bought about from a deep seated respect – gone are the box ticks and tokenistic agendas.

The wider festival and the economics of support

Pivotal to the festival is the presentation of the TARNANTHI Art Fair by Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute on the opening weekend. It generated over $600,000 in sales this year, $150,000 up on the 2015 event. This is important as it is money that goes direct to the artists and art centres, and gives visibility to an economy that sits as a foundation to the artworks we see in galleries and museums. Both have to exist.

This year that sense of support ran across TARNANTHI. In another project – exhibited at the South Australian Museum and a painting auction at Tandanya – raised almost $170,000 through The Purple House to secure a renal Dialysis Centre in Pukatja (Ernabella), South Australia, which will open in July 2018.

And an auction of boomerangs and woomeras, made by cultural leaders Mervyn Rubuntja and Kevin McCormack and reimagined by leading Australian contemporary artists, raised $22,000 for the Iltja Ntjarra/Many Hands Art Centre and the Namatjira Legacy Trust via an auction at AGSA.

The message was strong; this is a legacy that has to be sustained and – as costly as it might be due to their remote locations – the Aboriginal art centres across Australia are a vital part of the contemporary art ecosystem and need our funding support. Recent lessons have taught us that we can not exclusively rely on government anymore.

With regard to partner venues and exhibitions, returning was JamFactory with an exhibition of contemporary furniture and design by Nicole Monks and Yolngu weavers of Elcho Island titled Confluence, and an exhibition of “fluro fashion bags” by Malaa Thaldin artists from MIArts Centre Mornington Island.

At Adelaide’s newest venue ACE One was the exhibition Next Matriarch (until 9 December), featuring First Nations women who represent the next wave of sovereign female voices in contemporary art. And in one of the city’s oldest venues, Santos Museum of Economic Botany presented Entwined (until 28 January 2018) – a pairing of contemporary prints from Yirrkala made in response to string figures collected and documented during the 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, with artists from Bul’bula Arts making string to celebrate this ongoing tradition. It was a very sensitive and considered exhibition.

Read: Next Matriarch review

Worth mentioning also is South Australian Museum’s NGURRA: Home of Ngaanyatjarra Lands (until 28 January 2018), which takes a different curatorial tone but throws up a great contemporary story of Country and engagement. It is super accessible, and unveils some great engagement with tradition, from soap sculptures to haircuts that lift traditional designs.

This year the festival also stretched to Port Adelaide, up to Handorf, Seppeltsfield and across venues city wide. There is no shortage of engagement across different audiences and publics, and therein lies the real value of TARNANTHI – its geographic footprint.

This festival is about building legacies for the future. While we might review it for its merits as an exhibition or a festival, what is really on show is the way past and present, Indigenous and non-Indigenous come together and start to break down silos. The very platform of commissioning work, funding practice and embedding this legacy city wide – nation wide – is without doubt its greatest success.

TARNANTHI at the Art Gallery of South Australia is showing until Sunday 28 January 2018. For further information visit tarnanthi.com.au.

Gina Fairley travelled to Adelaide courtesy the AGSA.