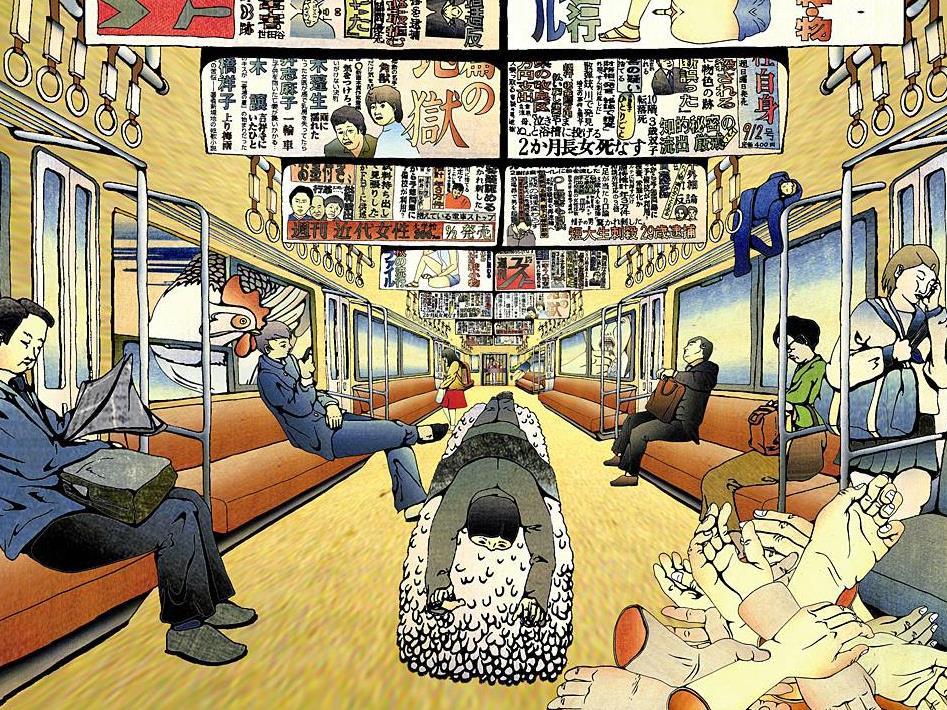

Tabaimo, Japanese commuter train (2001)

The visit of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to Australia last week served to underline the tensions between Japan’s past and present. To an extent this is also the subject of Japanese contemporary artist Tabaimo’s immersive video installations at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA).

Born Ayako Tabata in 1975, Tabaimo ‘came of age during Japan’s traumatic transition from prosperity to austerity’ during the ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s. As curator Rachel Kent articulates, Tabaimo perceives ‘a sense of “discontinuity” between old and new Japan’; ‘a concurrent shift away from communal to more individualistic values’ that have accompanied social and economic liberalisation.

Tabaimo’s installations are a fusion of past and present creative practices. Her animations are informed by the discrete linear detail and vibrant colouration of 19th-century ukiyo-e woodblock prints, particularly those of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Tabaimo’s combination of ukiyo-e compositional techniques with penetrating social commentary recalls the prints of Japanese-American artist Masami Taraoka, whose AIDS series of the 1980s featured uncanny imagery of geishas enveloped in giant flaccid condoms.

The MCA has clearly invested a great deal in this exhibition, which represents Tabaimo’s most significant solo show to date. It consists of six video installations in custom-built gallery spaces, two of which – mekuru meku ru and TOZEN – were commissioned by the MCA. Also included is a collection of intricately rendered pen and ink drawings that are testament to Tabaimo’s acuity as a graphic artist. The drawings, which juxtapose vigorous botanical forms with decaying human flesh and bone, bring to mind American modernist Georgia O’Keeffe’s celebrated Horse’s Skull paintings of the 1930s, only with a little more thrust. The illumination of these works on paper from behind using embedded light fixtures is a curatorial masterstroke. The individual drawings also serve to remind the viewer that animation can be a gruelling process. All of Tabaimo’s frames are drawn by hand, with each video taking six to twelve months from start to finish.

The most interesting work in this exhibition is Japanese Commuter Train (2001), a large hexagonal installation that simulates a suburban train ride. Passengers board and alight the train, with the surrounding sprawl of the city clearly visible through the ‘windows’ and a soundtrack of locomotive screeches and bumps. Tabaimo uses this mundane urban experience to highlight social discord. The ride is punctuated by cryptic pieces of text on a white screen that prefigure bizarre happenings on board. ‘A lizard’s casting off its tail’, for instance, foretells one passenger’s deliberate severing of his forearms, which litter the carriage floor. The act of amputation is an abrogation of moral and social responsibilities; the lizard sheds its tail by way of diverting predators and eluding capture. Although the amputee is eventually incarcerated by the conductor, there is little reaction from fellow passengers. Tabaimo’s commuters seem to engage in a kind of practised obliviousness by way of adapting to the vagaries of urban existence. Tabaimo invites the viewer to draw their own conclusions as to the work’s overarching significance – while an incisive social commentator, Tabaimo is no polemicist. At the end of the ‘journey’ this illusory ‘world-within-a-world’ is dramatically dispensed with by the omnipotent artist – the train is swept up by a cleaner.

The twelve months that Tabaimo spent in London from March 2003 seem to have had a definitive impact on her iconography. Her later works, exhibited in the northern gallery, feature organic imagery that is frequently isolated from any broader context – feet and hands, waves, bubbles, flowers, moths and hair. They deal with more abstract themes – of continuity in the face of change, vitality and decay, weightlessness and gravity, womanhood. The MCA-commissioned mekuru meku ru (2014) is a monumental work, spanning the ground and first floor walls and ceiling of the gallery. Its central motifs – the moth wings, the long flowing hair, the fluids that trickle down the picture plane – allude to femininity. At the outset of the video loop, the viewer is seemingly enclosed in a box, a possible reference to the difficulties faced by Japanese women in a deeply patriarchal society. The most striking feature of this work, however, is Tabaimo’s focus on pattern and surface which culminates in an expanse of fluttering moth wings. The effect is truly mesmerising.

Rating: 4 out of 5 starsTabaimo: Mekurumeku

Museum of Contemporary Art, 140 George Street, The Rocks

www.mca.com.au

3 July – 7 September