Exhibition installation view ‘Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium’ at the ANSW. All artworks © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Photo: AGNSW, Christopher Snee

Sexuality, identity, provocative acts, flowers, friends and celebrity sitters – these are the timeless portraits by the late photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989), which were made largely in the 1970s and 80s in New York City.

A new exhibition of his work at the Art Gallery of NSW captures that glorious period – a hedonistic time of creativity and experimentation, and one that Mapplethorpe was centred within.

Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium was developed by the J Paul Getty Museum and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation and the AGNSW. Co-curator of the exhibition Britt Salvesen, of LACMA, was in Sydney for the opening, and suggested the main themes of the show were Mapplethorpe’s iconic figure studies and male nudes; his portraiture more generally and floral still lifes.

Exhibition installation view ‘Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium’ at the ANSW. All artworks © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Photo Suellen Symons

The exhibition has been drawn from Mapplethorpe’s archive, which was acquired in 2011 by LACMA and the J Paul Getty Museum, and includes some 120,000 negatives, 3,500 Polaroids and correspondence.

Timothy Potts, director of the J Paul Getty Museum, said the exhibition provides the most comprehensive and intimate survey of Mapplethorpe’s work ever, and described the exhibition as ‘a must-see for anyone with an interest in late 20th-century photography and the cultural scene of New York in the 1970s and 1980s.’

‘Dr. Michael Brand, in his former role as director of the Getty Museum, was instrumental in securing the Mapplethorpe acquisition, so we are particularly delighted to have the Art Gallery of NSW present this exhibition in Australia,’ Potts added.

So what of the archive has come to Sydney?

Mapplethorpe studied and loved art history. He worked mainly in a studio with assistants helping him with lighting, photographing friends, lovers and for commissioned portraits. He wanted to be taken seriously as an artist. This works were documentation and a celebration of the cultural era as much as it was a play of pure form.

Formally the photographic work consists of square format, mainly silver gelatin prints, however there are also a smattering of platinum prints, which Mapplethorpe turned to for the portraits and some flower arrangements.

It was his spectacular flower studies, however, that colour was saved for. They take on a subtle sexuality, brilliant in their formal compositions and perfect technique.

Poppy 1988; Jointly acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The J Paul Getty Trust. Partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by The J Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

Interested in S&M images, Robert Mapplethorpe experimented with collage from gay magazines, before realising this fell short of the aesthetics he was after. He then moved on to experiment with the photographic medium (initially through polaroid portraits) and later filtered the influence of the imagery affiliated with S&M into his work.

Mapplethorpe was “sexing up” the language of photography by routing sex through the classic of idealism of the human form, much like the ancient Greeks did. His idea was to compose images of S&M men & women (but usually men) and nudes with the same traditional aesthetics given to still life or portraiture, but using confrontational sex (the “X” files).

By doing so, it became a political stance about homosexuality, and by proxy promiscuity, to be more acceptable. The political edge comes in because he’s being honest in his “documentation” (which is staged) and by daring to push boundaries showing sadomasochistic rough sex and making it more acceptable by the art establishment.

Photography made in New York before and during the AIDs epidemic was about the gay lifestyle, even down to his final image where he confronts his own mortality from the disease, he remains defiant. Viewing this show, you might argue that definite energy is still palpable in death.

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman 1984; Jointly acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The J Paul Getty Trust. Partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by The J Paul Getty Trust and The David Geffen Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

What drove Mapplethorpe?

In another life he said he would have been a sculptor. Is this quote emblazoned on the wall of the AGNSW to give us a hint that Mapplethorpe was on par with Ancient Greeks’ love of the classical form rather than Michelangelo or Rodin?

His nudes do exude sexuality and his work does appear sculptural. The formal qualities of the image were as important to him as the content itself, according to Isobel Parker Philip, curator of photography at the AGNSW.

His portraits of 80s superstars still offer us an allure after all. Deborah Harry (1978 printed 2011), gorgeous as always, scrutinises the camera; Paloma Picasso‘s delicious profile (1980); Isabella Rossellini exudes her Blue Velvet magic; Yoko Ono (1988, printed 1989) engages the viewer; Cindy Sherman (1983, printed 2010) does not disguise herself, while Andy Warhol (1986) is also just himself and David Hockney is relaxed.

There are older models, whose portraits are just as moving as the younger ones, such as Louise Nevelson (1986, printed 1990) and Louise Bourgeois (1982, printed 2010) for example, and Sam Wagstaff, Mapplethorpe’s older patrician lover who gave him his Hasselblad camera.

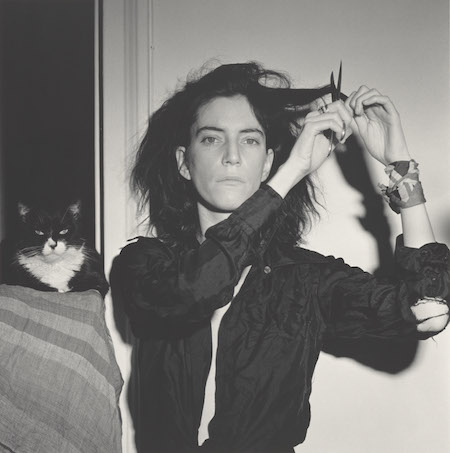

It’s a natural segway to the section in the exhibition, “The Sculptural Body”, that not only includes images of classic bodies of beautiful – yes, sculptural black men – but also Lisa Lyon (his muse after Patti Smith moved away to Detroit with her musician husband).

In the beginning it is all lightness of being with Patti Smith posing with horses, until we put the headphones on and hear her phenomenal voice, which sounds hoarse in this 70s performance film – honest, guttural, grating, experimental film making about performance.

Patti Smith 1978; Jointly acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The J Paul Getty Trust. Partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by The J Paul Getty Trust and The David Geffen Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

Having read Patti Smith’s 2010 tome Just kids on her life with, and without, Robert Mapplethorpe – and having lived in New York City myself in the late 80s – I know that it was an exciting time where artists collaborated and encouraged each other’s dreams. It was a time before the internet and mobile phones when images had more impact, and nightclubs were where everyone went to meet up.

It was during that time when I saw Robert Mapplethorpe’s work at the Uptown Whitney Museum in 1988. He was still alive at the beginning of the show, but passed away the next year. Like many artists, Mapplethorpe’s work had a strong impact on my own career as a photographer, and that exhibition captured a zeitgeist. The works were printed much larger in scale than they are shown here at the AGNSW, but only some of the content was the same. How did it stand the testament of time?

Joe, NYC 1978; Jointly acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The J Paul Getty Trust. Partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by The J Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

It was shocking, not just because it was 30 years ago, but because the S&M lifestyle had some chilling fall-out at that time, including a memorable murder of a young homeless man shot dead in bondage by an upper West side gallerist. It was hard to separate the acts, and they were very confronting images.

How often does art confront us with such brutally? The answer is not that often.

At the AGNSW by contrast, the alluded to ‘X’ portfolio images are printed very small so that they are hardly there, in keeping with a family gallery viewing public.

The Gallery explained the scale: ‘It is worth noting that the Gallery is exhibiting Mapplethorpe’s X, Y, Z portfolio prints as they appeared in the portfolio themselves. The scale is intrinsic to – and specified by – the portfolio format. While he did print some works that appear in the suite of portfolios at a larger size (to be displayed as singular images) the smaller scale prints appear as Mapplethorpe produced them for the portfolio context.’

There is a notice that warns sexually explicit images are in the exhibition, but it is possible to not really be confronted, as they are so minimal in comparison to the work I saw in New York in 1988.

It is a much tamer show here, but none-the-less worth seeing for the aesthetics of a photographer artist who championed the gay life style and S&M, but also who captured the culture of his era.

Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium

Art Gallery of NSW, Domain Road Sydney

27 October 2017 – 4 March 2018

This is a ticketed exhibition.

There is a complementary Lost in New York film series on at the AGNSW Domain Theatre from 28 October – 4 March 2018; see the Art Gallery of NSW website for program details.