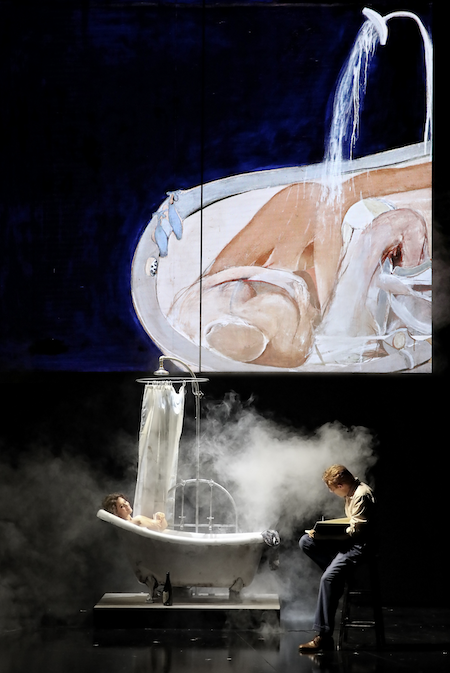

Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia’s 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House. Prudence Upton

One of the advantages of premiering a new production is that there is no meter for comparison. The long awaited, and much talked about, Opera Australia production Whiteley – modelled on the tumultuous life of artist Brett Whiteley – opened earlier this week (15 July) to maddening applause and ovation. There was, however, a moment of doubt whether it would be pulled off.

The first act struggled, and at times felt a disconnect with the vibrant, free passion that we associate with Whiteley’s paintings; the curtain coming down on Leigh Melrose as Whiteley leaving the audience with the lament ‘Bugger’.

While the word was an expression of shattered dreams, as Brett and his family were deported from Fiji for illicit drug use, it captured the flat feeling of that the first act. Bugger indeed.

But the production gained momentum in the second act, and romped home in a blaze of energy and bravado; the liberetto, score and dramatic tone finally coming together.

Created by composer Elena Kats-Chernin and playwright Justin Fleming, Whiteley is Opera Australia’s first newly commissioned work since Bliss in 2010 – and the investment in new homegrown work by our national company was welcomed.

OA Artistic Director Lyndon Terracini said of this commitment: ‘It’s important that we continue to tell Australian stories and create new works; as an art form we have to keep moving forward with the way we present opera and combining this story with our new digital staging, I’m confident it will attract new people to our audience.’

Julie Lea Goodwin as Wendy Whiteley, Kate Amos as Older Arkie Whiteley, Nicholas Jones as Michael Driscoll and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia’s 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House. Photo Prudence Upton

It is Kats-Chernin tenth opera, and her second commissioned by Opera Australia following The Divorce (2015). Often turning to contemporary subjects – drawing out the gender fluidity of Iphis in Ovid’s Metamorphosis for example, or adapting Peter Jackson’s 1995 film Heavenly Creatures for the production Matricide – the composer was a good fit for Whiteley.

She has created a musical landscape that is daring, eclectic, free and bold.

Kats-Chernin has captured the tensions inherent in Whiteley’s story – his fiery creative temperament, the restlessness, and drive for perfection – pairing unpredictable instruments together, such as a play of pizzicato (plucking of strings) with bold saxophone and percussion – sliding between the minimal and drug-induced mania.

The audience starts to feel the rhythmic gestures of Whiteley’s brushstrokes or his boozy outbursts through her music. It is a great score. Kats-Chernin’s vision was completed by conducted Tahu Matheson and the Opera Australia Orchestra, who bought her textural nuances perfectly to life.

The liberetto created by Fleming, however, feels less cohesive – at times too caught in the delivery of fact, and at others pitched too far towards the poetic rather than storytelling.

The first act is particularly thin, moving through a kind of checklist chronology of Whiteley’s early life: roguish child, meeting Wendy, winning a travel scholarship, standing in front of Europe’s great masterpieces, life in London, success, Whiteley’s introduction to drugs, a disenchanted stay in New York, and that drug bust in Fiji.

It is a lot of ground, and in the attempt to authentically capture this biography the emotion gets lost. It almost feels rigid – the antithesis of Whiteley. Fleming said the challenge was not what to write, but what to cut out – that is apparent.

However, in the second act he finds the dramatic tone a little more, and the liberetto sits better in sync with Kats-Chernin’s score.

Largely staged in Whiteley’s Lavender Bay home, this act offers moments in the Whiteley narrative that are less predictable, such as Whiteley’s journey to Bali with friend Joel Elenberg to see out his last days, a fiery ‘blow up’ with writer Patrick White (Gregory Brown), and the humorous blokes tête-à-tête with Michael Driscoll (Nicholas Jones), Wendy’s lover.

Emotion – in full operatic range – finally enters this opera.

The use of OA’s new LED screens work well for this production. Highlights are the full stage immersion of Whiteley’s Untitled Red Painting, which the Tate bought from his 1961 exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery. As the youngest artist purchased by Tate, that record still stands today.

The cast of Opera Australia’s 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House. Photo Prudence Upton

Video designer Sean Nieuwenhuis also did a beautiful job in animating Whiteley’s view of the harbour from his Lavender Bay balcony in the second act, where Melrose as Whiteley stretched and splashed the painting into life on a scrim.

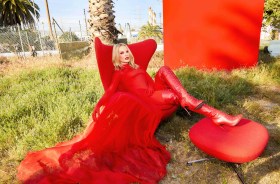

Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia’s 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House. Photo Prudence Upton

Whiteley is the third new production in OA’s digital season, and the investment is proving a solid one for the company, offering a dynamic viewer experience and a more environmentally friendly approach to operatic staging.

From Aida, to Madama Butterfly, Anna Bolena to Whiteley, the malleability in tone that the screens offer is remarkably diverse, a contemporary inflection at home with even the most traditional of operas.

English baritone Melrose is compelling as Brett Whiteley, and holds this production together. His emotional range and vocal strength match what was needed for this role, which moves from a kind of vulnerable ambition, to blazing fame and eventual self destruction – always tinged with anxiety and a heady creative spirit.

Julie Lea Goodwin as his muse and wife, Wendy, captures her poise, radiance and charm, but the character remains in the supporting role. She is a well matched with Melrose’s vocal strength.

Despite these vocal strengths, there are moments of missed opportunities – the scene depicting Whiteley and Wendy iconic bath paintings feels stiff – incomplete – as does their first meeting. This, however, is balanced by a beautiful energy on stage of the couple’s honeymoon. It is the first moment in this opera that the audience starts to feel their connection on stage.

Julie Lea Goodwin as Wendy Whiteley and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia’s 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House. Photo Prudence Upton

In supporting roles, Kate Amos as the Older Arkie Whiteley brings a truth to the production frustrated by her parents and yet caught in the lustre of their lives. While a little stiff on stage, her voice had a strength that was compelling. The other roles largely had a cameo quality.

I find it a curious choice to conclude this opera in Wendy’s garden, to shift the focus away from Whiteley and leapfrog through the tensions that followed his death to arrive at this place of resolution, and utopian memories and living ghosts.

Overall, this opera gains momentum and that was appreciated by the audience on opening night with warm applause.

It is a great Australian story, a great story for opera but more importantly, it is a narrative of our times. This is what opera needs to continue to grow, and together with OA’s fresh approach to high-tech staging, there are great wins in this production that will ensure its success.

3.5 stars ★★★☆

Whiteley

Opera Australia

Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

15 – 30 July 2019

Composer: Elena Kats-Chernin

Librettist: Justin Fleming

Conductor: Tahu Matheson

Director: David Freeman

Production Designer: Dan Potra

Video Content Designer: Sean Nieuwenhuis

Lighting Designer: John Rayment

Assistant Director: John Sheedy

Consultant: Ashleigh Wilson