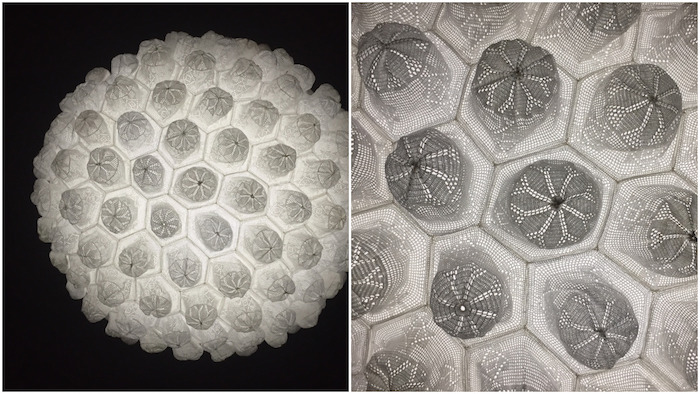

Installation view, Shireen Tawell, musallah (2017) at ACE Open; pierced copper; courtesy the artist. Photo by ArtsHub.

Australia’s population is diverse, and yet, representations of that diversity have been somewhat slow in filtering into art world dialogue and gallery programming. While it has happened – and quite successfully on occasion – the artists that have brought forward that conversation have been celebrated deeply, but there is still room for change.

A new national collective of Muslim Australian artists, curators and writers, eleven, are featured in an exhibition at ACE Open in Adelaide, coinciding with Adelaide Festival and the Biennial to amplify this message and their visibility.

They claim: ‘eleven uniquely straddles contemporary art, academia and grass roots community engagement with the intent to amplify the intellectual, robust and dynamic conversations about Muslim artists in Australia.’

ACE Open Director Liz Nowell continued: ‘This exhibition marks an important moment in the shifting landscape of Australian culture. Offering an essential counterpoint to the often hostile “debate” surrounding transnational migration, multiculturalism and faith, this exhibition amplifies the experience of time through personal, political, cultural and spiritual variations to invite new dialogue about the vital contribution of an alternative frame of reference to societal “norms”.’

Waqt al-tagheer: Time of change has been co-curated by Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Nur Shkembi. It does not subscribe to the ‘one size fits all’ when describing to audiences what the art of a ‘Muslim artist’ or ‘Islamic artist’ might look like in Australia. Rather, it is a nuanced survey that offers what the curators describe as ‘personal understandings of being’.

Beyond labels

Walking into the exhibition, the immediate impact is the choice of black paint for its walls, which is on trend at the moment and works well in this situation to make these artworks jump out in high frequency, as if someone just cranked up the volume.

In particular that black backdrop works perfectly for the work of Abdullah M.I. Syed, Aura 11 (2013), a back-lit mandala-like form constructed from white crocheted prayer caps, or topi. It is the first work viewers see and sets a tone for this exhibition that is both sensitive and deeply layered in meaning and reference.

Abdullah M.I. Syed, Aura II (detail) (2013) hand-stitched white crocheted prayer caps (topi), Perspex and LED light, 127 (diameter) x 54cm. Courtesy the artist; photo ArtsHub.

Syed’s work is paired with that of Abdul Abdullah, a photographic piece titled Journey to the West (2017), a self-portrait where the artist wears an ape mask and refers to himself as the ‘monkey king’, using words such as ‘monstrous’, ‘threatening’, and ‘villainous other’ to describe himself. It could be argued equally as a placard of self-perception as much as one of perceived popular opinion.

The two present a very different message – a kind of see-saw dialogue that works in this instance to survey a moment and a movement. I am not talking “art isms and movements”, rather a zeitgeist that feels unresolved.

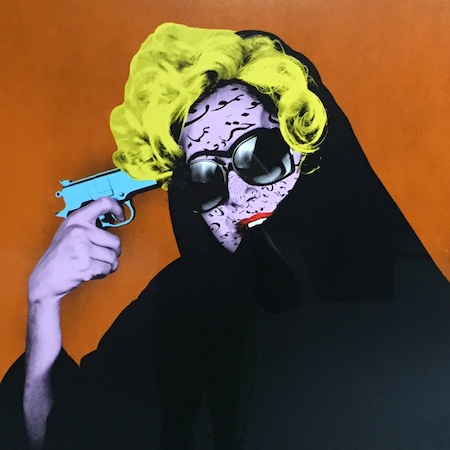

Moving into the main gallery space, again the viewer is faced with dichotomous pairings. To the left is a suite of five photographic works from Hoda Afshar’s Under Western Eyes series (2013) that combine a ‘pop-art style [and] familiar signs of Islamic identity to challenge the dominant representations of Islamic women that circulate in the Western art gallery’, as she explains.

Hoda Afshar’s Westoxicated #3 (2013) from her Under Western Eyes photographic series; courtesy the artist.

Sitting opposite Afshar’s punchy pastiches is Shireeen Taweel’s ethereal installation musallah (2017, pictured top), a perforated sheet-copper hoop that hovers above the ground casting shadows. One can’t help but be transported to the architecture of traditional mosques. But the reference is a little closer to home than those historic monuments many of us have experienced on trips abroad. musallah (2017) responds to the oldest standing mosque located in Broken Hill (NSW), the site of a former camel camp and populated by Australia’s first Afghan settlers.

Symbolically, it speaks about how those beliefs are transposed to a new place; this thing that is always there hovering like a guardian and yet still separate.

You can’t help but be drawn to both works – one incredibly beautiful and the other tugging at the advertising cues often used to ascribe identity.

As one moves deeper into this exhibition you start to feel the texture and nuances of this conversation broaden.

Zeina Iaali’s hand-cut Perspex moulds echoe those used to create traditional Arabic sweets, and speaks about gender roles across time; Abdullah M.I. Syed’s reconfiguring of US currency into objects that reference a timeline of trigger events – almost as you would collect a box of life’s souvenirs – things that personally and culturally define you.

Central to the gallery is Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s 500 Books, hand-carved from wood and reflecting on a childhood memory of his father’s rescue of the last remaining copies of a soon-to-be-pulped Sufi text.

Installation view: Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s 500 Books, with Khadim Ali and Hoda Afshar’s work in the backround; photo ArtsHub.

These are rich works, and the didactic labels across the exhibition help expand their narrative to viewers.

Also working from a Sufi tradition is Khaled Sabsabi, who adds a video installation to this exhibition. At the Speed of Light is a floor-based 11-channel work that takes the idea of ‘kashf’ (a Sufi concept dealing with knowledge of the heart rather than the intellect) and attempts to express that via light.

It presents 218 hours of video footage of the sky above Sabsabi’s home, which the artist then compressed into a single second to essentially visualise the speed of light, or 299,792,458 metres per second.

Sabsabi explains that the work is a meditation on Sufism and the significance of notions of the absolute, Heaven, angels and the unseen, and how these beliefs may complicate a scientific perception of time.

Installation view: Khaled Sabsabi’s At the Speed of Light at ACE Open (2018); photo ArtsHub

Rethinking tradition through contemporary conversations

While the work is disparate in medium, style and energy, the viewer can think across this exhibition and the connections between the works. Overall the exhibition curation is strong, and was an Adelaide Festival highlight.

We can all learn from these conversations, and my feeling is that this is just the start. But with that there is a warning. As long as these conversations are pulled out and packaged up, they are kept siloed – amplified yes, but nevertheless separated. I would have assumed that the greater position is for these artists, and the conversations they present, to be woven into the complexity of contemporary Australian art.

For example, Abdul Abdullah’s repeated inclusion in the Archibald Prize at Art Gallery of NSW, Khadim Ali’s huge mural that greets people as they arrive at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, and Khaled Sabsabi’s work in the current Biennale of Sydney. Inclusion grows understanding more broadly.

Rating 4 out of 5

Waqt al-tagheer: Time of change

Co-curated by Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Nur Shkembi

ACE Open, Adelaide

3 March – 21 April 2018

The exhibition features the work of: Abdul Abdullah (NSW), Abdul-Rahman Abdullah (WA), Hoda Afshar (VIC), Safdar Ahmed (NSW), Khadim Ali (NSW), Eugenia Flynn (VIC), Zeina Iaali (NSW), Khaled Sabsabi (NSW), Abdullah M.I. Syed (NSW) and Shireen Taweel (NSW).