Image: Installation view, Unfinished Business: Perspectives on art and feminism 2017, ACCA. Photo Andrew curtis.

In 1891 a handful of dedicated women petitioned door to door to gather almost 30,000 signatures from women all over Victoria, demanding the right to vote on equal terms with men. This document is now in Victoria’s archives and is known as the ‘Monster Petition’ because of its size; 260 metres long it takes three people three hours to unroll it. This petition was an important stepping stone in our new nation’s history.

In 1902, a year after federation, Australia became the first country in the world to give white women the right to vote in a federal election. Sadly it took another 60 years, until 1962, for Indigenous women and men to be formally granted that right.

Now, 116 years later the feminist quest has broadened and evolved: the gaze is not only focused on issues such as domestic violence, sexual harassment and the right for equal pay; it highlights the hypocrisies and discrimination in our society for other marginalised groups such as indigenous and transgender rights.

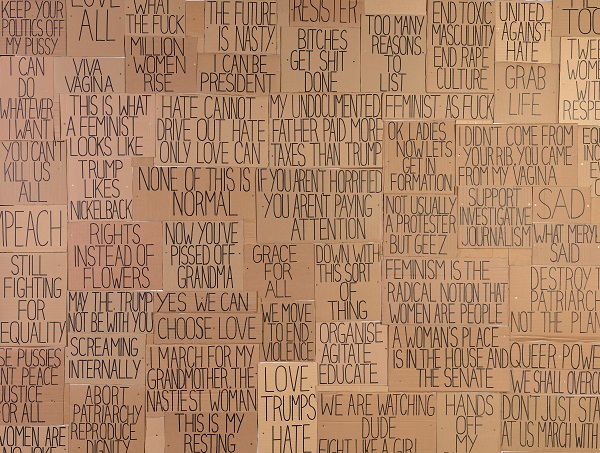

Image: Sarah Goffman, I am with you 2017. Cardbord, permanent marker, dimensions variable. Photo Andrew Curtis. Supplied.

‘Feminism now intersects with a whole lot of other contexts – gender, age, race and ethnicity…[it] is a form of activism in that it seeks social change and transformation,’ said Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) Artist Director Max Delany.

Part of ACCA’s ongoing series of big picture exhibitions Unfinished Business, developed by Max Delany along with ACCA curator Annika Kristensen and a team of leading Australian artists and curators including Julie Ewington, Paola Balla, Vikki McInnes and Elvis Richardson, incorporates a diverse range of ‘voices, practices and debates.’

Through a wide range of media such as paint, print and performance to photography, video/film along with archival material, the exhibition questions, explores and creates an ongoing dialogue about what it means to be a feminist. Showcasing over 40 works with newly commissioned and recent work along side historical projects from the 1970s to the present. The exhibition runs until late March in conjunction with a series of workshops, discussion forums and performances.

ACCA is a wonderful venue for this kind of diverse and exploratory exhibition. Cavernous rooms segue into more intimate spaces taking the viewer on a journey of the feminist voice in Australia.

The large spaces make navigating the exhibition comfortable while the multimedia presentation makes it an accessible exhibition for people with hearing and sight impairments. At the centre of the exhibition space is a new commission by the legendary furniture designer Mary Featherston and artist Emily Floyd. The piece was inspired by a Featherston’s illustration from the community childcare newsletter Ripple,1977.

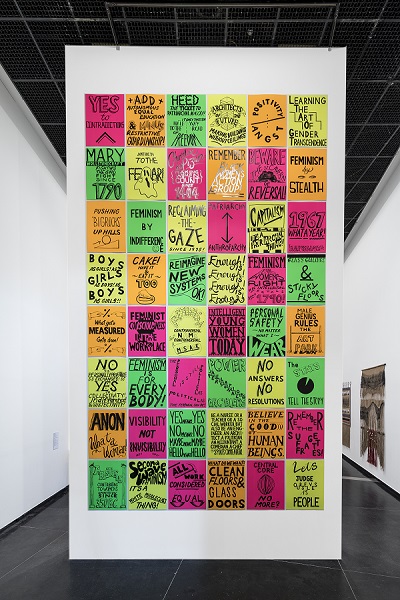

Image: Kelly Doley, Things learnt about feminism #1-95 2014. Ink on card, 95 sheets, each 60.0 x 52.0 cm. Photo Andrew Curtis. Supplied.

Round Table (2017) is a sculptural piece acting as an inter-generational dialogue between the two artists, as well as a meeting place to gather and discuss ideas throughout the exhibition period. ‘It’s acknowledging the role of the domestic kitchen table as a site for gatherings and consciousness-raising conversations,’ said Kristensen.

Man Cleaning Up, (2017) by Natalie Thomas, is a gently humorous new performance work has left its mark – a fluorescent work vest – at the entrance of the show and involves a man on his hands and knees cleaning up at the opening and various events throughout the duration of the exhibition.

Racist Texts (2014/17), on the other hand, is a confronting monument, looming eight metres high of books stacked one on top of the other, by Ali Gumillya Baker. The work is composed of racist books – from picture books and history to current texts – reinforcing just how many racist texts are out there and the way they infiltrate our views of indigenous people.

Black Velvet by Fiona Foley, (1996) consists of 12 dilly bags sewn with red vulvas and is a reference to a euphemism used by white men for black women in Australia, another sobering work of black oppression. Frances (Budden) Phoenix’s works also deal with female oppression. Pieces such as Relic, (Mary’s blood never failed me) (1976-77), a collage with embroidery, crochet, lace and paint, and Get your abortion laws off our bodies, (1980), a crochet milk-jug cover with pink beads and carpet fragment mounted on board – are powerful statements using traditionally female mediums that speak about the inherent nature of womanhood, the mail gaze and the way women are often deifyed, but also see as objects to possess and control.

The problem with this exhibition is that there are so many powerful and arresting works that cannot easily be captured in this review. It is an intelligent and carefully curated exploration and commentary on the feminist evolution in Australia, which is supported by contextual material and catalogue.

Finishing on the 25 March for anyone in or visiting Melbourne this is an important exhibition to see. In the social media age of #METOO this exhibition reinforces the notion of why we must all be feminists.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Unfinished Business

111 Sturt Street

Southbank, Melbourne

Free entry