Installation view Tony Albert: Visible, Queensland Art Gallery (2018); photo ArtsHub.

When one considers an exhibition, they might take in its sightlines – how the eye moves from one artwork to the next – the transition between gallery spaces, and what catches the eye at the edges of the show.

The sightlines for Tony Albert’s survey exhibition Visible, presented by the Queensland Art Gallery, work on both a micro and a macro level.

The exhibition sits like a kernel in a sea of consideration. You can view important historical Aboriginal artwork in the gallery’s Australian Collection and Amata women’s paintings in the Gallery’s Watermall Atrium. In a humble way, Tony Albert finds his place in the narrative of Indigenous Art in Australia.

Conceptually, it extends Albert’s premise for this exhibition, which questions how we have visualised Aboriginal Australia as mere self-serving décor and thuggish lads, and while the aesthetic may have changed, he asks, has the intention also changed?

Central to Visible is the collaborative video installation, Moving Targets (2015), first shown in 24 Frames at Sydney’s Carriageworks. It was made with Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Artistic Director Stephen Page, in the wake of the 2012 police shooting of two Aboriginal teenagers joyriding in Sydney’s King’s Cross.

A burnt-out car sits in a darkened gallery with a kind of locked-in intensity; its internal panels and bonnet housing video screens. That intensity is amplified by a wallpaper of digital portraits drawn from Albert’s award-winning photographic series, Brothers (2013), seemingly baring witness.

Collaboration is a key part of Albert’s practice. Brothers was made with young men from the Kirinari Hostel in King’s Cross. It sits adjacent to – and in sight of – a newer body of photographic portraits, The Force is with us (2017), where Albert, similarly, has turned back on visual stereotypes, handing over the ‘artistic direction’ to the kids from the remote Western Australian, Warakurna Arts Community to reclaim their visual identity.

The tone shifts from being a target to self-appointed super heroes and warriors.

The exhibition is bookended by Albert’s signature series – Aboriginalia and his text wall works. Individually these objects point to an ignorant past, but en masse they point to a pervasive present.

Having collected over 400 of these kitschy, largely household objects, since childhood, Albert is a kind of self-appointed guardian of this chapter of Australia’s visual history – the only evidence of an existence.

Born in 1981, it is a shockingly recent and confronting flaw, that Aboriginal people were not seen in the media, in books etc., but relegated to a 1950s-70s souvenir market as their own visibility. He calls into court our collective subconscious to confront our racist past, and lack of resolve with our racist present.

Albert presents these objects in museum cases, working some kind of alchemic magic converting the language of kitsch and racism to museological authority. We again feel the echo of the exhibition’s title.

A new work, Moving the Line (2018), adds to this growing collection with hundreds of playing cards that have been folded and painted. It shows Albert’s care and dexterity. There is a strong relationship with to the placard boards Boy (2018) and Girl (2018) drawing on a desk of vintage playing cards.

Installation detail Mid Century Modern (2016), digital print; photo ArtsHub.

Completing the suite of Aboriginalia is the digital installation, Mid Century Modern (2016) – a grid of photographs of ashtrays with faux-Aboriginal designs sitting atop vintage tea towels. With cigarette butts stubbed in to, or objects dried upon the faces of Aboriginals, it calls us to check our “gauge for respect”. It seemingly carries added weight with the recent fight against the fake Aboriginal souvenir art trade.

Read: Government invests $150,000 into digital labeling to combat fake Aboriginal art

It also presents an interesting conversation between the actual object (sitting opposite in the flesh) and its “presented” digital tiled rendition as “contemporary art”. The prints somehow free the object from its tangibility allowing it to be read at a different level.

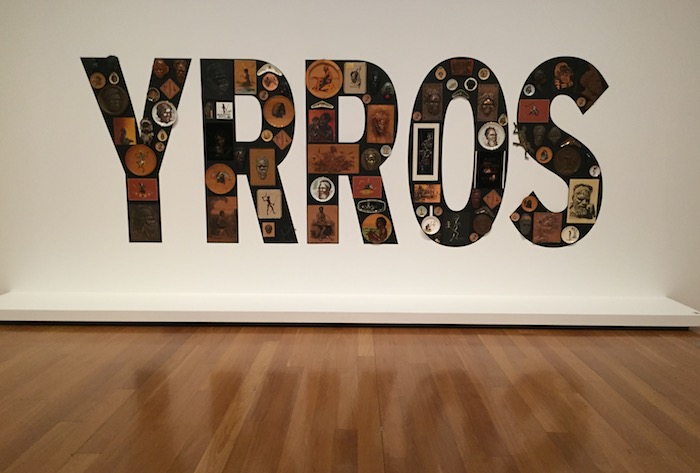

Completing this exhibition is a selection of Albert’s important text works – Headhunter (2007), Sorry (2008), Pay Attention (2009–10), exotic OTHER (2009/2018), and whiteWASH (2018), which has been created for the exhibition.

Their play of reflections on the gallery floor seem to make these works, echo or ring in our white ears.

When Albert made Sorry it was in the wake of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations, unveiled at the QAG’s 2008 exhibition, Contemporary Australia: Optimism. Ten years on for this show, Albert requested the letters be reversed to demonstrate a lack of sincerity in the origins of the word. Visibility fades to invisibility.

Sorry (2008), installation view QAG Tony Albert: Visible; photo ArtsHub

Albert holds a mirror up to our own collective memory and places it in scrutiny, but with such great eloquence and elegance; with humour and the sharp honed one-liners that meet their target.

And so we return to the beginning, on the exhibition’s sightlines – it’s the capacity to look beyond yourself, to look forward and to look back, to reach out and to return what you have been given. Tony Albert’s Visible is a lesson to us all.

Rating ★★★★★

Tony Albert: Visible

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane

Curated by Bruce Johnson McLean, Curator of Indigenous Australian Art at QAGOMA

until 7 October 2018