Exonemo, Kiss, or Dual Monitors, 2017, HD video, cables, dimensions variable. Installation view Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (2018); Courtesy the artists.

Are you among the many who are increasingly concerned about just how much of your personal data has been hijacked by Big Tech?

A new exhibition curated by Michael Do, with the assistance of Isabel Rouch, taps into the zeitgeist of innovation versus concern. Do we face it or embrace it? The truth is, most of us take an apathetic path and choose to do nothing, continuing to absorb our daily diet of Big Tech’s feed.

Aptly titled The Invisible Hand, this exhibition at 4A Gallery pulls together both commissioned and recent work by a group of artists who are collectively considering how digital platform technologies are exploiting technological convenience to co-opt personal data.

Do explained: ‘Household internet penetration and use is at its global highest in the East Asia region and The Invisible Hand will explore how in this region, platform technology companies have the power to alter the course of history.’

Do refers to recent tech-led scandals, such as the way Cambridge Analytica have manipulated contemporary politics in America, Thailand and India, and the coordinated cyber-attacks on public health records in Singapore.

Working with artists Simon Denny (New Zealand), Exonemo (Japan), Sunwoo Hoon and Mijoon Pak (Korea), and Baden Pailthorpe (Australia), The Invisible Hand is all about this lived frontier – and it is both incredibly humorous and incredibly dark.

Walking into the lower gallery, visitors encounter the work of exonemo (Sembo Kensuke and Akaiwa Yae) hanging centrally: Kiss, or Dual Monitors (2017) – two screens sandwiched together in a full-on “pash”. They float above a mosh pit of antiquated computer cables, which have a vascular quality as a life source.

Exonemo formed in 1996, and their practice has run parallel to the development of the Internet. As Do says, ‘it’s both a demonstration and criticism of it’. This work pushes against the slick branded interface we are led to believe will change our lives for the better, but fails to talk about technology’s waste, or this minefield of connectivity to “the other”, over which we have no control.

It sits in the space with the dual monitor piece, In Live Streams (2018), where the viewer confronts screens with a live feed video that not only questions the very act of looking, but the role of narcissism within the Internet with its perpetual validation feedback loop.

Moving into the upper galleries the exhibition continues to have an interactive quality.

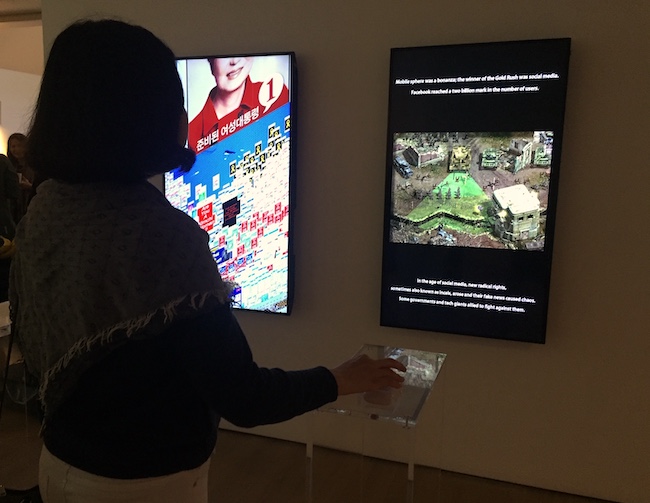

Sunwoo Hoon’s The Flat is Political (2018) highlights the contribution technologies have had in South Korea’s political sphere. Through a webtoon format, the work begins with a single pixel that aggregates to illustrate moments in the nation’s political history, from the 1980 Gwangju Uprising to the #metoo movement.

It is paired with a collaborative work by Pak Mijoon, Flat Earth (2019), which uses the same webtoon style, but tracks the development of the Internet parallel to social media.

Both pieces are interactive, allowing the viewer to appropriately scroll and skim through history, playing the very game of social editing that these works critique.

Sunwoo Hoon, Flat is the new deep, 2018; Commissioned by Gwangju Biennale, 2018 with support from Christina H. Kang. Courtesy the artist; and Sunwoo Hoon and Mijoon Pak, Flat Earth, 2019, Commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the artists.

Do makes the point that since the creation of the first website in 1991, over one billion websites have proliferated across the globe, with 2.5 trillion Internet searches made every year – not to mention the 700 billion friendships formed via Facebook alone.

‘The technological devices upon which we rely daily are increasingly prefixed by the word “smart”. From phones to cars to homes, digital devices respond to our desires with an exacting discernment that tailors our experience of the world,’ said Doh.

It is fitting then that at polar ends of the gallery, in a kind of tech face off, are the works of Baden Pailthorpe and Simon Denny.

Pailthorpe’s installation One and Three PCs (2019) comprises an elaborate computer system whose sole purpose is to self-generate an image of itself. There is a nice correlation to Exonemo’s self-feed loop downstairs.

Much has been said about AI in recent years – from the fear-mongering, “the bots are coming to get us”, to a glowing utopian future of self-driven cars. Using an image-generating AI program Palithorpe takes “the mickey” out of AI for its inability to creatively think beyond its given intelligence.

Baden Pailthorpe, One and Three PCs (2019) (detail), installation view 4A Gallery 2019; photo ArtsHub

On one monitor we see a Richter-esque image that is a heavily pixelated aggregated image of itself; a second monitor exposes the limitation of understanding itself; between them is this slick skeletal, slightly arousing, sculpture that houses the computer.

Do explained: ‘It’s a computer trained to understand itself, but can’t actually do that. You can’t cut a stick of butter with a butterknife made of butter – it is that same idea.’

Completing the exhibition are two works by Simon Denny which look at the way the ‘tech industry subsumes individuals and cities in its operations’. We are talking about the economics of technology and its capacity to impact our lives.

Following a residency in Shenzhen – a former fishing village on the Pearl River Delta that has now become China’s Silicon Valley and home to 12 million people – Denny mimics the kind of showcases associated with tech street vendors in his work Shenzhen innovation paradigm – Mass Entrepreneurship – 2.

Simon Denny, Front: Shenzhen Mass Entrepreneurial Huaqiangbei Market Counter in OCT Theme Park Style – Battery, 2017; Courtesy the artist and Fine Arts, Sydney and Rear: Real Mass Entrepreneurship, 2017, video; Courtesy the artist and Fine Arts, Sydney

Not too dissimilar to the traditional museum pedestal, it sets up all sorts of strange conversations about authority and permissions. The case is emblazoned with technical advertisements and slogans.

Shenzen is home to companies Foxconn and Huawei, with Foxconn manufacturing a lot of goods used in our iPhones, explained Do. He added: ‘We don’t realise how intimately – we in Australia – are connected to this city and how much they know about us.’

The work is accompanied by the video projection Real Mass Entrepreneurship (2017) which collects and collates screen grabs that speak about economic policy implicated by technology.

This is a clean and elegant show; it’s not cluttered spatially or bogged down in demanding technology. Do described it as ‘a warm exhibition but cold in many ways.’ We would have to agree.

There is a lightness and humour present that offers an interesting landing point for these conversations. In doing so, it is more successful in broaching these contemporary conversations.

4 ½ stars: ★★★★☆

The Invisible Hand

Curator: Micheal Do

Curatorial Assistant: Isabel Rouch

Artists: Simon Denny (New Zealand), Exonemo (Japan), Sunwoo Hoon and Mijoon Pak (Korea), Baden Pailthorpe (Australia).

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney

27 June – 4 August 2019

www.4a.com.au