Installation view Peter Cooley’s work in RocoColonial (2019), Hazelhurst Arts Centre; photo ArtsHub

When you think of the two milestone political and aesthetic periods – early 18th century Rococo and Colonialism – it is not an intuitive, ‘glove-fit’ connection that one draws.But for artist, academic and curator Gary Carsley it was a no-brainer to bring these two periods together in an exhibition that ‘materialises an imagined overlap’.

Carsley hinges his exhibition RocoColonial on three key dates linking the wider political rupture these two periods presented. Then as now, issues of globalisation, accelerating inequality and the systematic abuse of power by a ruling elite were threatening the established order of things, he explained.

It is a time space landscape that is alert and curious, but as a viewer walking through this exhibition, we are left asking whether it is too much of a stretch?

The back story helps. Carsley explained: In 1770 while Captain Cook was charting Australia, Marie Antoinette was marrying the future Louis XVI of France, a moment that marked the end of the Rococo and the beginning of the Colonial periods.

In early 1793, as the first free settlers were landing at Port Botany (close to the Hazelhurst Gallery), King Louis XVI was being executed by guillotine at the height of the French revolution.

And in 1815, when Louis’s brothers were being restored to power and seeking to reverse the Revolution’s reforms, Governor Macquarie was proclaiming the future town of Bathurst (where the exhibition will travel to next), on Wiradjuri land.

Looking at the artworks by the 15 artists, there is not that palpable grasp one feels connecting individual pieces, apart from a loose thread of cartouches and cameos, glitz and sparkle.

Installation view RocoColonial Hazelhurst Art Gallery 2019; photo ArtsHub

It lacks that stereotypical horro-vacui of excess that we expect with the Rococo period – a period known for its theatrical decoration combining scrolling curves, gilding, Chinoiserie, elaborate ceramics, sculpted moldings, wallpapers and trompe l’oeil frescoes. While some works in this show do embrace bling and the cartouche, it is that notion of excess that is missing, except perhaps in the fantasy fashion by Romance was Born.

The most obvious inclusion that points to the period are the murals by architect Renjie Teoh that frame pieces of Romance was Born and Marc Newson’s take on a chaise lounge, Orgone Lounge 1989. These, along with a shell work by Bidjigal artist Esme Timbery, are the two critical reference points for Carsley in RocoColonial.

Chimera and Galah by designers Romance Was Born with cartoushe by Renjie Teoh; installation view RocoColonial; photo Artshub

The word Rococo is a derivative of the French term rocaille, which means ‘rock and shell garden ornamentation’, and that slippery mash point of periods in exemplified in Timbery’s installation Shellworked Slippers that speaks of the Indigenous craft practices of La Perouse, close to Botany Bay where Cook landed, but also of the impact of colonialism on Aboriginal people.

Originally commissioned in 2008 by Campbelltown Arts Centre, its rectangular format has been manipulated to echo Cook’s hand-drawn map of Australia – a cartouche in itself believes Carsley – with the removal of slippers form its heart, a metaphorical homage to the Stolen Generation.

Esme Timbery Shellworked slippers 2008, reconfigured for RocoColonial 2019; photo ArtsHub

Peter Cooley’s menagerie of ceramic birds (pictured top) similarly reach for connection with the Rococo practice of collecting animals for lifestyle decoration, glitzy ceramic, and the popular practice of sugar birds on dining tables, as revealed by Carsley’s research.

Was this Cooley’s intention in their making, or have they been hijacked for curatorial play? Just as this exhibition raises heady questions of history’s cycled flaws, for this writer it also leaves one pondering the curatorial role of forcing existing disparate works together under a heady reflexive theme.

Where it does get it right is in the new works created for this exhibition. Among the highlights are Deborah Kelly’s Venus Envy (redux), and Jennifer Leahy’s photographic series The Deep Surface.

Kelly reuses and reinterprets the image of Marie-Louise O’Murphy, the 14-year-old model for Francois Boucher’s 1752 work Jeune Fille allongée (Reclining Girl). A table with gilt mirror, floral arrangement (which subtly censors the work), create a tableaux that superbly leaps the chasm of periods, while still pointing to contemporary body politic and gender conversations.

Deborah Kelly, Venus Envy (redux), 2019, mixed media, installation view RocoColonial; courtesy the artist, photo Artshub

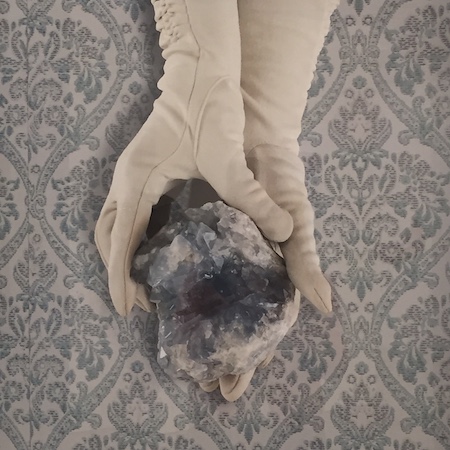

For Leahy, she wanted to understand the connection more, so organised research residencies with the Sutherland Shire Historical Society, drawing upon its collection of women’s gloves, and the wallpapers from colonial Abercrombie House and the Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, both in Bathurst.

Learhy’s use of these objects speaks to the dispossession of resources by colonisers, and the overlay of European fashion, but also echoes Carsley’s finding that one of King Louis’ mistresses started the fashion of collecting gem stones and minerals.

Detail from Jennifer Leahy’s photographic series The Deep Surface (2019); courtesy the artist, installation photo ArtsHub

Similarly, Tècha Noble’s new work Whispering Heads is a direct play with the phrase ‘off with their heads’, and the Rococo extravagance of wigs worn in the period – again caught between perceptions of power and beauty. And of course, and exhibition that speaks of colonialism in Australia is not complete without the work of Joan Ross – again a perfect fit for RocoColonial.

Tècha Noble Whispering Heads (2019), installation view RocoColonial; photo ArtsHub

It goes without saying this is a complex exhibition. The curatorial thesis of this synergy of time, place and politics for RocoColonial pops the lid on fresh thought and undoubtedly pushes us to think beyond written conventional histories.

However, the exhibition doesn’t flow per se, but rather feels like a collection of individual works with their own erudite considerations. I am curious how the exhibition will present in its second iteration in Bathurst, where compressing the work into a smaller space might arrive at that visual excess, and start to bounce and push, jar and excite a little more.

Regardless, this exhibition is a brave curatorial leap, and in our times of growing conservatism and neat acceptances, one has to champion the frontier it boldly embraces.

Rating: ★★★

RocoColonial

Curator: Gary Carsley

Artists: Brook Andrew | Tony Clark | Peter Cooley | Deborah Kelly | Belem Lett | Jennifer Leahy | Danie Mellor | Marc Newson | Técha Noble & Romance Was Born | Joan Ross | Justin Shoulder | Esme Timbery | Jenny Watson | Louise Zhang Cartouches: Renjie Teoh

Hazelhurst Arts Centre

4 May – 30 June 2019

782 Kingsway, Gymea (NSW).

Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

2 August – 22 September 2019