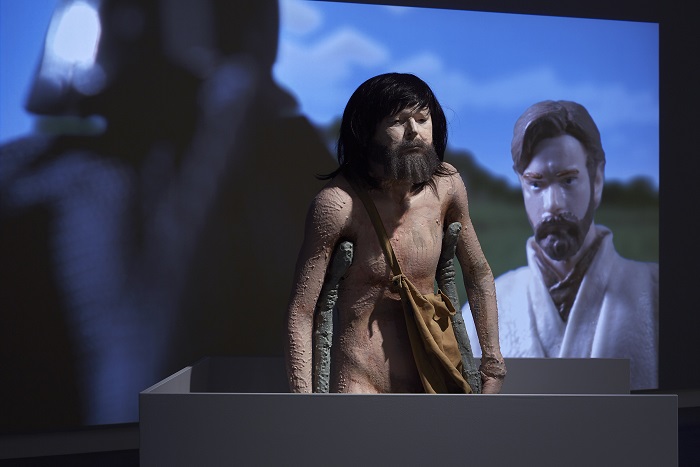

Installation view, No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne, 12 July – 21 October 2018, photograph by Christian Capurro.

In an era where the idea of surveillance can lead to notions of paranoia, discomfort and invasion of personal space and liberties, the title of the current exhibition showing at Buxton Contemporary, No One is Watching You, by New Zealand/Australian artist Ronnie Van Hout, has particular resonance.

Situated in Melbourne University’s College of the Arts precinct in South Bank, Buxton Contemporary, named after Michael Buxton who donated his significant private collection, is the latest edition to the group of University galleries. A mindfully designed building by Fender Katsalidis, it takes in the historical and vernacular of the area; its five interior galleries over two floors along with a teaching space also reflecting this considered approach to design. Large, rectangular rooms flow comfortably one to the other, allowing for easy visitor access and movement with lift and stair options; disabled toilets are also provided. In contrast however to this carefully considered environment the current exhibition by Ronnie van Hout works actively at confronting and provoking discomfort in the viewer.

Marking Buxton Contemporary’s first solo show this survey exhibition of van Hout’s work brings together almost 80 artworks drawing from both public and private collections in Australia and New Zealand and includes a major new body of work for this exhibition. It is the first of an ongoing series of solo exhibitions in which an artist’s oeuvre and practice is explored in depth. This exhibition plays with the idea of ‘watching and the watched’ through video, sculpture, painting, photography, text and embroidery.

Installation view, No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne, 12 July – 21 October 2018, photograph by Christian Capurro.

With a background in film studies, much of van Hout’s work reflects his ongoing fascination with the medium. Curator Melissa Keys has captured the sense of the cinematic well through careful lighting that builds on the drama and the shock value of the works. Like a film set the exhibition is composed of carefully choreographed dramas or vignettes from van Hout’s life, film, art history, science fiction and popular culture.

These are not works of beauty but they are pieces that will touch you, make you feel uncomfortable and perhaps cause you to reflect on that discomfort. On entering the larger exhibition spaces one is confronted with multiple works of hybrid, mini van Houts, roughly made and painted, that populate the space. These man-child sculptures starring blankly, sulkily at the viewer, clad in child’s pyjamas at once repel and elicit empathy. They perhaps uncomfortably capture that part in all of us that has never quite grown up. As Keys suggests, the characters are activated by the lives of those who encounter them.

Doom and Gloom, (2009), painted plastic, fibreglass on polystyrene, modelling clay and synthetic hair is a particularly uncomfortable exploration of the double. According to the catalogue, the work captures the zeitgeist of the time; van Hout explores the atmosphere created by the global financial crisis through a pair of grumpy, over tired twins. Using plastic moulds of his own face and ears stuck onto a hairdressers’ mannequin head, its roughly painted features and wooden paddle-like arms and hands make this pair particularly unloveable.

Installation view, No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne, 12 July – 21 October 2018, photograph by Christian Capurro.

But maybe what also repels us in van Houts work is the clear power play in the relationship. One twin is subservient to the other and this sense of the dominant and male ego is played out throughout the exhibition. Take for example the video of Brett and Michael, (2014) where van Hout plays both parts. Taken from a menacing 1998 thriller The Boys, it explores the psychology of uneven power relationships. But just when we think we’ve got it van Hout creates a twist; who is victim and perpetrator?

A body of smaller works on odd, distorted plinths reflects van Houts humorous take on aspects of the human condition. I should’ve done that ages ago, (2012), painted polyurethane and fibreglass, depicts a sausage with human legs and upside down head, suggesting something about natural bodily functions, generally done in private. The banana is another of van Houts reoccurring symbols of humour; used in 19th century vaudeville it has a long history in comedy. Van Hout draws from this historical lineage in Bad traveller, (2010), painted polyurethane and fibreglass, by creating a large banana with human limbs and face, reflecting something of his feelings of potency or perhaps impotency in the world?

Installation view, No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne, 12 July – 21 October 2018, photograph by Christian Capurro.

Made especially for the exhibition King Vader (2018), video installation and Bad fathers, (2018) painted polyurethane and fibreglass, comprises a caste of many male figures, some Ronnie hybrids and other adult Ronnies. Figures featured are from popular culture such as a rock musician or Christianity, Jesus in loin cloth and arms outstretched, or art history with a soldier slumped in a bath tub like the revolutionary in the painting Death of Marat by Neoclassical artist Jacque-Louis David. And then there’s Michael Angelo’s David, also wearing a helmet, but with rifle in one hand and iPhone in the other: a contemporary humorous take on notions of masculinity or a critic of the prevailing male dominance in the canon of western art? A good place to leave the work of Ronnie van Hout: provocateur and absurdist; a mirror to our inner selves or a display of masculine power or innocent fun. The exhibition may be any or none of these, its up to you the viewer.

A well curated exhibition that would have benefited from more interpretive material. Despite didactic panels, catalogue and floor talks something like a video in the foyer of van Hout in his studio or the interview with Melissa Keys, like that found in the catalogue, would have made this powerful yet demanding show a little more accessible to the uninitiated person off the street.

4 stars ★★★★No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout

Curator: Melissa Keys

Presented in association with Melbourne International Arts Festival

12 July – 21 October 2018

Buxton Contempoary, Melbourne