Installation view, Julie Gough’s Some Tasmanian Aboriginal children living with non-Aboriginal people before 1840 (2008). Found chair with burnt tea tree sticks, 288 x 60 x 50 cm. Collection: National Gallery of Australia. Image supplied.

A bundle of unfinished spears made from tea-trees are tightly constrained by an old wooden chair. Its wicker seat has been removed; the bare wooden circle of the seat holds the spears tight – a constrictive domestic embrace.

Looking closely we see that each spear carries a name burnt into the wood; the names of lost children – Tasmanian Aboriginal children who were living with non-Aboriginal people up until to 1840.

In the same room, an old trunk is propped open by a gun cleaning rod, allowing us to survey its contents. Within lies a blanket, on which shining steel pins spell out an old story from the Sydney Gazette about ‘A native male infant … rescued from a fate of barbarous indifference.’

Viewed together, these two artworks by Trawlwoolway woman Julie Gough speak volumes about the experiences of Aboriginal Tasmanian children long before the phrase ‘stolen generations’ was ever coined.

Julie Gough: Tense Past is a major new exhibition by the Tasmanian Aboriginal artist, writer and curator at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery (TMAG). Presented in partnership with Dark Mofo and curated by Dr Mary Knights, TMAG’S Senior Curator of Art, it is the first major solo exhibition in a state or national institution for Gough, who is represented by Hobart’s Bett Gallery.

Julie Gough, HUNTING GROUND (Pastoral) Van Diemen’s Land, 2016-17 HDMI video projection, colour, silent, 12:26 min, 3:4 ratio edited by Angus Ashton.

Across four gallery spaces at TMAG, Tense Past interrogates colonial history and the impact of colonisation on Tasmania’s First Peoples – then and now. The exhibition draws on Gough’s 25 years of practice, and incorporates artworks and artefacts from TMAG and other major collections to create new interpretations and layers of meaning out of a series of striking and creative juxtapositions.

This conversation between Gough and the past, between historic injustice and contemporary concern, is perhaps best illustrated by the presentation in one section of the exhibition of Governor George Arthur’s Proclamation to the Aborigines (a four-strip pictogram attempting to explain the concept of equality under the law, copies of which were nailed to Tasmanian trees where the plaques might be seen by Aboriginals and settlers alike) and a video work which precedes it.

The proclamation’s shape echoes a series of pages seen in an earlier gallery: extracts from letters, journals and other historic texts relating tales of frontier violence. Like the Governor’s proclamation, these documents – as depicted in the powerful video work Hunting Ground (haunted) – have also been nailed to trees, except instead of explaining equality they recount tales of horror and barbarity.

The video showcases these stories almost dispassionately, first showing us an almost casual, snapshot-like view of the landscape before moving closer to reveal the shocking texts, reminding us that throughout Tasmania we see a landscape which settlers claimed as their own only through the attempted extermination of the island’s First Peoples.

Questions about the perpetrators of such violence – who was complicit in the killings? Who benefited either directly or indirectly from the attempted genocide? – are also raised in the exhibition, again through focused and deliberate juxtaposition.

Knut Bull’s portraits of James Barter Wiggins (circa 1851), a Hobart builder, contractor and publican, and his wife, Mrs Mary Anne Wiggins (nee Bishop) (circa 1853) depict the prosperous couple some two decades after the Black War was fought in Tasmania. The pair are soberly dressed, double-chinned, their eyes cool and confident – but what did they see earlier in their lives? What did they know?

Beside the oil on canvas portraits of Mr and Mrs Wiggins hangs another painting: Thomas Napier’s Woureddy & Trucanini (1832). Less finessed than Bull’s work, its placement in the exhibition, and the cruder execution of its subjects, perhaps implies that the artist considered his subjects of less importance than a doughty Hobart burgher and his wife. Today, it is a work of far greater significance.

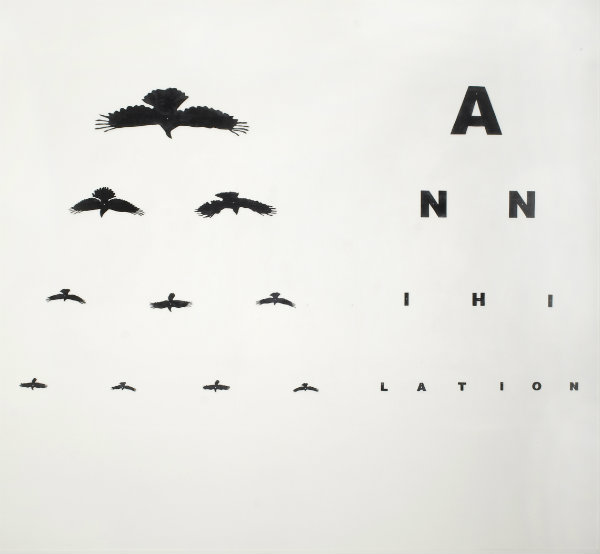

Nor are questions of complicity always rooted in the past, with works like Human Nature and Material Culture (1994) critiquing the cosy and comfortable domesticity of more contemporary Tasmanians, while Murder of Crows (2011) draws on the visual language of ophthalmology to reflect on distance, insight, memory and the passage of time.

Julie Gough, Murder of Crows, 2011, courtesy of the artist.

From postcards which quietly highlight, in a faux domestic setting, the endurance of Tasmania’s First Peoples despite settlers’ active attempts to displace them and forget them, to a chilling reminder (via the title of the artwork We ran/I am. Journal of George Augustus Robinson 3 November 1830, Swan Island, North East Tasmania – “I issued slops to all of the fresh natives, gave them baubles and played the flute, and rendered them as satisfied as I could. The people all seemed satisfied with their clothes. Trousers is excellent things and confines their legs so they cannot run” (2007)) that a settler’s gift was rarely without ulterior motive, this survey exhibition of Gough’s work is compelling, moving and long overdue.

Knights’ insightful curation gives Gough’s potent, powerful and intelligent artworks even greater weight, ensuring that the artist’s authoritative voice speaks clearly throughout this expansive and provocative exhibition.

Four stars: ★★★★

Julie Gough – Tense Past

Presented by Dark Mofo and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart

7 June – 3 November 2019

The author’s visit to Hobart was supported by Tourism Tasmania and Dark Mofo.