‘If the future is to be worth anything’ rings true as a question for many in Australia’s art world today. It is an apt title for this ambitious survey exhibition measuring the pulse of contemporary art in South Australia.

Partway through the gestation process for the artists making work for this survey, COVID-19 hit and artists retreated to their studios. But this has given a sharper focus to Patrice Sharkey and Rayleen Forester’s curatorial probe.

This is the fourth survey exhibition of contemporary South Australian artists over the last two decades, following much larger survey exhibitions at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 2000 and 2013, and the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia (one of the two precursors to ACE Open) in 2010.

ACE Open’s gallery space is more confined, and gives an overview based on just ten artists and collectives. The resulting show feels more selective than its predecessors, but this exhibition displays an exciting and vibrant look at South Australia’s artists.

Diversity in themes and techniques

In 22 photo portraits, Carly Tarkari Dodd, a young Kaurna/Narungga and Ngarrindjeri artist, addresses head-on the offensive practice of categorising Aboriginality by skin colour.

Placed between the compelling photos are mirrored panels speaking back to the viewers with cruel racist text. The subjects of the portraits are overlaid with a signature Aboriginal iconography of dots, their faces showing a mix of emotions: from pride and optimism at a better future, to strength marred by weary endurance.

Carly Tarkari Dodd’s photographs address racism and pride, while Sandra Saunders looks at colonisation the museumification of Aboriginal culture.

Senior Ngarrindjeri artist Sandra Saunders considers the destruction of wildlife from the recent bushfires in her meticulous oil painting, the Museum of Sorrow.

The impact of colonisation, climate change and environmental destruction have been her subjects in recent years in paintings produced in a naive, untutored style.

Here, Saunders has appropriated a European quasi-Vermeer style to speak back to colonialism’s litany of damage. Her painting of an entrance to a museum of natural history, populated by a small number of endangered animals, suggests the pressing issue of mammalian extinction and the museumification of Aboriginal culture.

A more spare aesthetic underpins Sundari Carmody’s and Kate Bohunnis’s sculptural installations. For Carmody, it is the creation of a precise architectural space for contemplation; for Bohunnis, the oppositional forces on her body from metal and latex are resolved in the rhythmic movement of a pendulum.

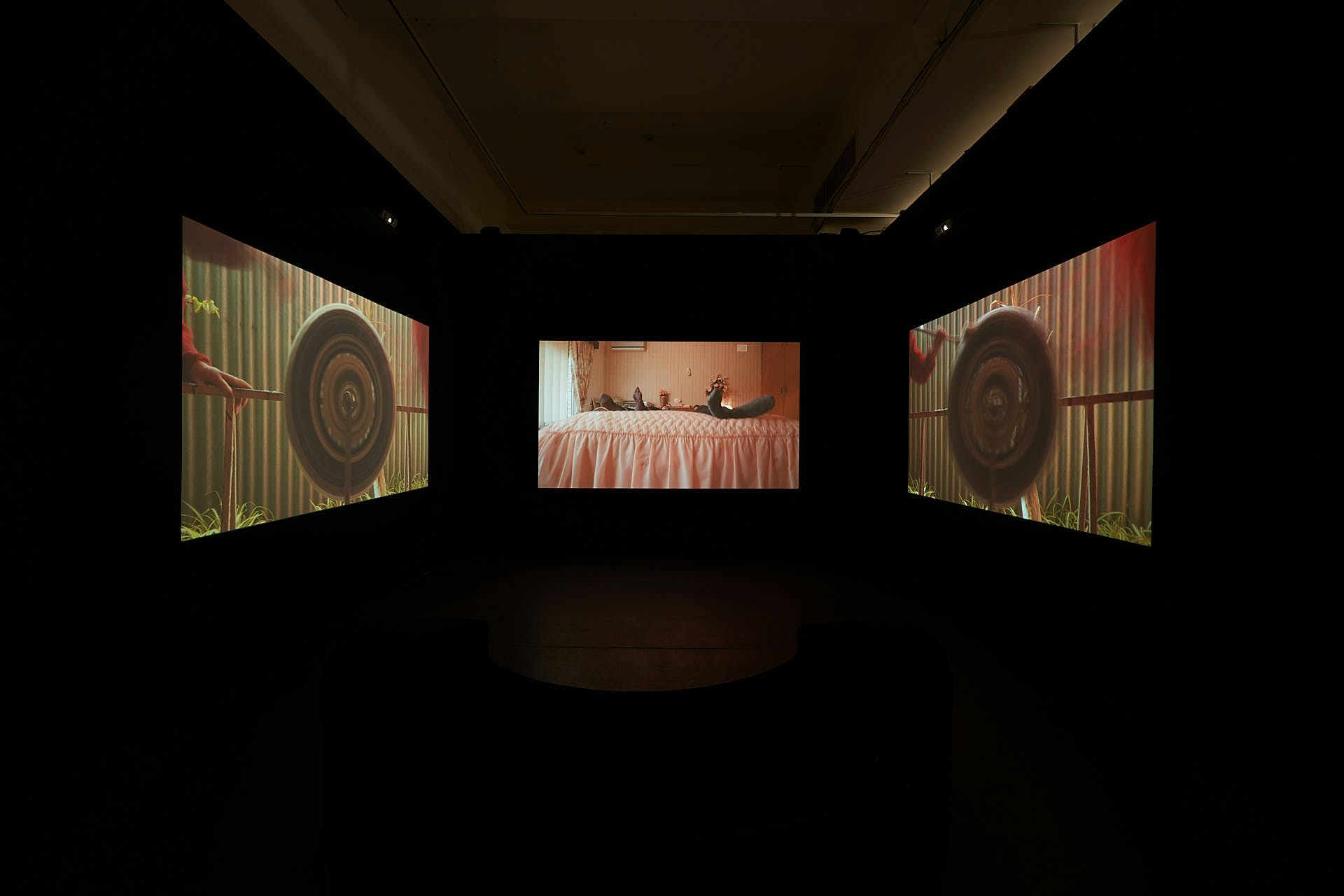

Emmaline Zanelli’s video explores her Nonna’s life in domestic and industrial workplaces.

Emmaline Zanelli’s video work looks at her Nonna’s life in domestic and industrial workplaces. Sam Roberts/ACE Open

The intergenerational legacy of memory is a conduit for shape-shifting images oscillating between realism and abstraction, drawing on the embrace of movement as the basis for a visual language from Italian futurisism.

The candy colours of Matt Huppatz’s trio of prints continue his investigation into the transgressive and liminal world of queer masculinity.

Matt Huppatz’s prints investigate queer masculinity, while Kate Bohunnis used her own body to create her sculpture work. Sam Roberts/ACE Open

Overlaid on each image of a nightclub scene is text: Lights and Music (Communicate), Lights and Music (Release), Lights and Music (Express). These allude to the affectionate language of a club scene oozing with sensory overload.

Experimentation runs through the exhibition, and writing from fine print magazine under editors Forester and Joanne Kitto adheres to this, their performative style of criticism and text becoming an exhibit itself.

Yusuf Ali Hayat invites the viewer to step through his perspex doors. Sam Roberts/ACE Open

Another work steeped in experimentation is Yusuf Ali Hayat’s interactive, interlocking perspex doors in Baab Al-Salaam, the name referencing a gate at Mecca. Each door is anchored in an Islamic geometry of five diamonds, and covered in a dichroic filter, altering visibility.

Hayat approaches his work from a migrant’s outsider perspective. In inviting audience members to pass through the doors, he explores the universality in his personal experience.

Tutti artists show an eclectic range of work, some drawing on found materials as in James Kurtze’s The Kooky Time Machine, while Aida Azin’s arresting street culture painting Toodles Galore is an in-your-face confrontation with racism, sexism and cultural imperialism.

The conundrum of the human condition

It is surprising, given the shift to globalism, there have been four narrowly focused survey exhibitions of contemporary South Australian artists over the last two decades. It seems there are more artists per capita in this state than elsewhere in the nation.

This may explain the intense scrutiny of contemporary practice in these shows, or it may reflect a geographical anxiety, but it differs from the accepted practice in Australia where survey exhibitions tend to be national rather than state-based.

Sundari Carmody’s In the Air sits in the front gallery of ACE Open. Sam Roberts/ACE Open

A few more mid-career and senior artists would have added depth, balance and a sense of comprehensive coverage to the exhibition. Nevertheless there is vibrancy, experimentation and risk, supported by a philosophy of decolonisation and transcultural ethics.

The exhibition reflects the lively breadth of practice and exploration of ideas in contemporary practice in South Australia. As the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor reminded us, artists ‘try to find ways in which their ideas and art can explore the eternal conundrum of the human condition.’

In this moment of COVID, this reflection has been heightened by artists working more within their own radius of daily life.

If The Future Is To Be Worth Anything is at ACE Open, Adelaide, until 12 December. ![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article by Catherine Speck, Professor, Art History.