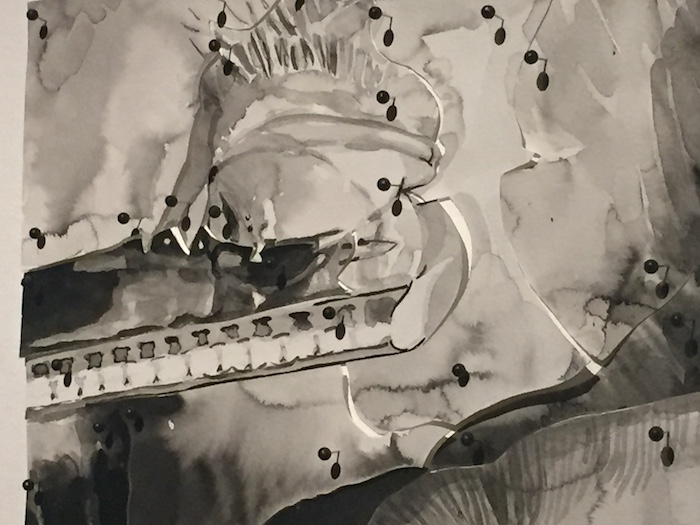

Locust Jones The end of the beginning, New Year’s Eve to April fools 2018 (detail); installation view AGNSW; photo ArtsHub

Drawing has had a huge revival in recent years with a total rethink of the medium, and how it informs other practices.

This year’s Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) is a case in point. With the title Playback, the gallery has pitted this exhibition as a reimaging of history, in particular, exploring the crossovers between drawing and the moving image – between the digital and the analogue.

This is the third edition of the biennial presented at the gallery, established when the institution decided to axe the long held prize of the same name in 2012.

This year, that prize has been revived, and will be presented by the National Art School in the alternate years to the biennial, which will allow the discourse around the medium to remain in the spotlight.

The AGNSW exhibition presents the work of just eight artists: Vernon Ah Kee, Sharon Goodwin, Laura Hindmarsh, Locust Jones, Dorota Mytych, Jason Phu, Lucienne Rickard and Nick Strike. Each has been selected for the way they respond to images found in art history, archives, newspapers, cinema and online.

Art Gallery of NSW curator Matt Cox said: ‘There are drawings in Playback that also invoke the moving image as they unfold and reform in a process of recycling, and in so doing, the image, rather than being recovered or restored, becomes something other.’

But how does this play out for the viewer?

The exhibition is divided across two galleries, of which the tone feels quiet different. The first gallery varied greatly in scale, energy and presentation. While in the second gallery – the works are presented against black walls – the drawings stick largely to a black and white palette, yet punch out of their drawing’s traditional frame.

What immediately strikes you most is the presentation of these works: Sharon Goodwin works directly onto the wall and embeds a 3D element; Jason Phu’s work is a video performative drawing, while Nick Strike uses collage, push pins, film and video to speak of the medium.

We only see a fragment of Jones’ scroll l (pictured above), which unfolds like ‘a visual ticker tape of the 24-hour news cycle’. It captures that quality of constant noise – of streaming – with no sense of a beginning, a solution, or an end. It is cinematic in scale and gesture.

For Jones, there is no overall vision of what the completed image will look like, unrolling just a segment each day to work on, responding to news of the moment. As Cox describes, it is daily drawing without a filter.

There is a lovely connection between the work of Locust and Hindmarsh which sit adjacent in the first gallery. Hindmarsh also plays with the idea of streaming information. While these works couldn’t be any different aesthetically (one expansive; the other intimate and presented in traditional museum stock frames pointing) neither subscribe to a hierarchy of draftsmanship or subject.

Rather it’s the idea of time that these drawings capture. Hindmarsh replicates screenshots from computer searches of old films, complete with mouse cursor, progress bars, and toolbars. Her work is an online experience of the past.

In the second gallery, Strike and Mytych also pay a nod to the mechanics of analogue film. Strike manages to present a work that is exciting to look at, very layered and engaged for the viewer, but one that is also so conceptually tight and erudite. It combines a video with a mock film spool of drawn frames.

Installation view Nick Strike’s work, Box of Clouds (2017); photo ArtsHub

Taking his cue from film’s construct of 24 frames per second, Strike has created 24 collage drawings that are pinned together. He obsessively replicates the moment when film blisters under heat and an image is lost.

Using a found 16mm film to recreate this experience with a magnifying glass – and inspired by Dali’s iconic dada film, Un Chien Andalou (1929) – the central moving image starts to make sense.

I couldn’t help but take a photo (and Instagram) a detail of one of Strike’s pinned collages, only later to learn that he was interested in the role that viewers would play by reanimating these frames on their smartphones. The collection of which becomes like a ‘flip-book’ of that pre-digital film fame. Cox points to Dada artist Hannah Hoch’s use of cut photographs, and re-joining of the segments as collage, to build his thesis of cyclical historical context in this exhibition. Similarly, he points out that the cubist painter Georges Braque was inspired by cinematic montage to rethink spatial and pictorial representation.

Detail of Nick Strike’s work, Box of Clouds (2017); photo ArtsHub

‘These developments saw the blurring of lines between sculpture, photography, painting, film and drawing,’ said Cox.

We see the links across this exhibition with Dorota Mytych, who examines drawing across four video monitors, and also pays a nod to the Dada movement with what she calls her ‘moving drawing’ – drawing objects created in sand. They carry that rough, gritty, soft lens, low-res quality. As she explained: ‘The images appear and disappear, recalling the chemical process of photography that produces images according to exposure times.’

She added that she wanted this to be a ‘slow work’ – a slow engagement by the viewer.

Sitting kind of separate to these ideas, is the work of Ah Kee. Showing a recent work from his ongoing Unwritten series, which has been made in response to the violence of the 2004 Palm Island riots, the work pits the rhetoric of race and identity through its stifled visualisation.

Vernon Ah Kee, installation view Art Gallery NSW, Unwashed (2017-19), from the series Unwritten; photo ArtsHub

A central portrait is presented with text on either side – black-on-black that fades into the black gallery walls and punching the portrait on a white field which in turn confronts the viewer.

Cox describes the face as ‘not fully formed but pulsating in a way that suggests struggle and aspiration; as though pressing against the skin of the canvas, wanting to emerge, to be born from a suffocating mask.’

The two styles have become signature to Ah Kee, and increasingly he has been presenting them together, expanding the drawing context.

While entirely different in medium and tone, there is an odd connection with Jason Phu’s installation with it’s learned bodily reference.

In his statement, Phu recalls – and relates – to a conversation with a Chinese calligraphy student who speaks of process being drilled into him: ‘I get it, I can’t unlearn the Concept, the Media and the Drawing from my art school days,’ said Phu.

Jason Phu, I drew this, and then I did it (2018), installation view Art Gallery NSW, Photo ArtsHub

In contrast, the gestural narrative of Sharon Goodwin’s work feels a little thin, and unresolved in comparison, and a 3D element central to the work reads a clumsy as an after-thought. Positioned between the works of Locust and Phu only magnifies this, especially from a gestural or calligraphic position.

Equally, Lucienne Rickard’s two drawings presented on bulldog clips, struggle a little against the works in the second gallery. They do however make a connection from a curatorial perspective, executed on drafting film and also embracing an obsessive and laborious process.

This 2018 Dobell Biennial is a modest show, but it tackles a big topic – and does so with great consideration and elegance. It is easy to fall into criticism when so few artists are selected to unpack such a broad context of contemporary drawing, but Cox has done a great job at stitching together the foundations and nuances behind these disparate works.

I have to share the view that this drawing biennial is one of the better presented since the exhibition’s inception. It is not overtly caught up in trying to push the newest and the edgiest, but rather is a solid contemplation of the medium now.

Rating: 4 ½ stars ★★★★☆Playback: 2018 Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

7 July until 21 October 2018

The exhibition will tour regionally to the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre (16 March – 5 May 2019) and Orange Regional Gallery (12 October – 8 December 2019).