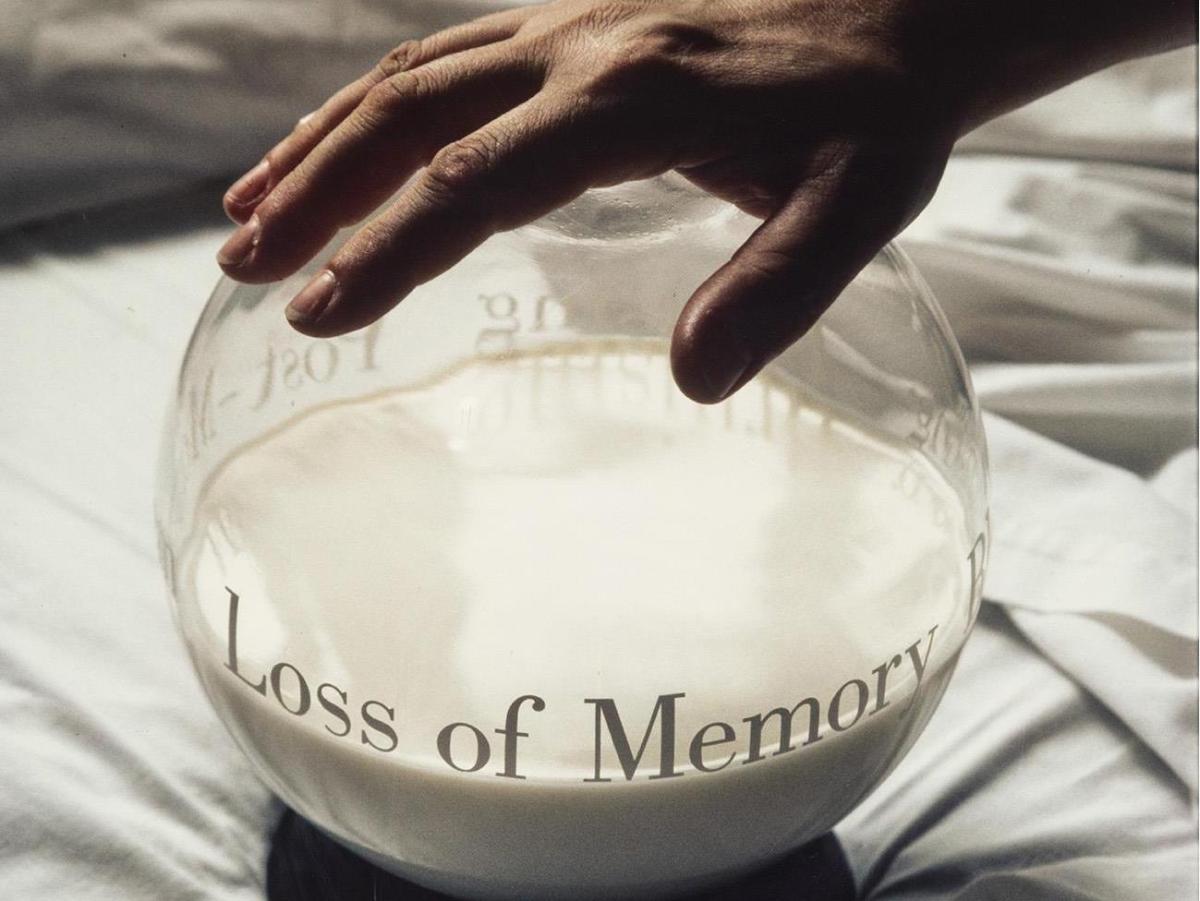

Detail of Maree Cunnington’s Loss of Memory From ‘Secretions’ 1997, Griffith University Art Collection; Photo Carl Warner

There is a feeling you sometimes get when you are witness to an important moment – a moment in history, a moment for change, an act of empowered voices. This exhibition captures one such moment.

Dark Rooms: Women Directing the Lens 1978 – 98 has been curated by Naomi Evans for the Griffith University Art Museum, in Brisbane, and surveys a moment in the history of photography and photo media in Australia when women took control of their own voice.

Evans explained: ‘Against the backdrop of the feminist movement and activism in arts and politics, many women artists during this period made work that refused the male gaze. Acutely aware of the ways in which the lens could empower or reduce the subject, they put themselves, friends, and family in the picture, and in doing so, changed the cultural landscape of Australia.’

Many of these images we know – creating a kind of joint-the-dots picture of Australian feminism – but there is also a palpable energy to this exhibition that forces us to remember, to rethink, and to ask questions of our own times.

The weight of that movement has incredible currency today in the wake of the #metoo moment.

Director Griffith University Art Museum, Angela Goddard said at the exhibition’s opening: ‘We feel in this moment of time, of the recent #metoo movement, slut shaming in politics, continuing sexual violence and casual brutality towards women; this exhibition is one that we need to see.’

Goddard added that the Museum’s commitment to the work of artists who challenge and confront remains part of the University’s acquisition priorities.

Have we moved forward? Do we still have lessons to learn? Looking back at this fertile photographic period, Evans gives us a dense exhibition consisting of over 60 works, largely drawn from the University’s collection and supplement by loans from the artists and other collections.

The story is told through works of pioneering artists such as Tracey Moffatt, Lindy Lee, Robyn Stacey, Jill Orr, Bonita Ely, Julie Rrap, Eugenia Raskopoulos – it is a roll call of recent Australian art history.

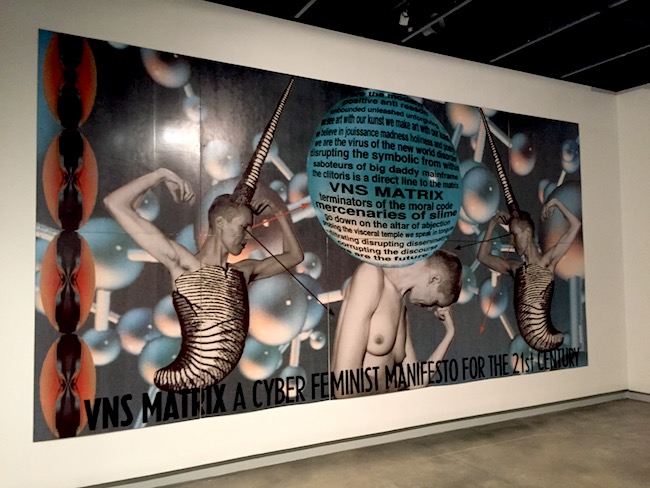

In all, there are 28 artists / collectives in this exhibition, which reaches a crescendo with the work of VNX Matrix (Virginia Barratt, Francesca Da Rimini, Julianne Pierce, Josephine Starrs) in the end gallery, with their 4-meter billboard, A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, made from a lithographic print.

Owned by Griffith University, this billboard first used the term ‘cyberfeminism’ and was installed outside the Tin Sheds Gallery, Sydney in 1992. The Adelaide-based collective came together to make work that engaged ‘with the sexualised and socially provocative relationship between women and technology,’ explains Evans.

Installation view Griffith University Art Museum, VNX Matrix A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century (1992); photo Artshub

With the affordability of snapshot cameras and new processing, photography had a boom in the 1970s and 80s. It was a period characterised by radical experimentation, from the immediacy of point and shoot to very staged compositions.

‘Artists referenced narratives of history and power, and appropriated elements from advertising, cinema, and television, but by the 1990s, computer-generated imagery and increased access to the internet offered artists new visual languages,’ said Evans. ‘Photomedia became an important way for artists to confront racism and the objectification of peoples; disrupt and subvert sexually violent imagery; and forge a renewed interest in psychoanalytic theory.’

Technology allowed a change in how artists made images; women photographers disrupted the narrative and changed what such images said.

Walking into the gallery, the first work encountered is Lindy Lee’s triptych Untitled (1987), which features three photocopies of a single page from an art history reference book, that the artist has taken to with ink to deface the male gaze.

I like this technology touchpoint across the exhibition, from Lee to VNX Matrix.

Lee’s triptych sits with other works of a more intimate scale – a velvet gloved first impression – a work from Eugenia Raskopoulos’ Goddess mother daughter series (1991), which takes a more autobiographical approach to speak of feminist art practice. She overlays the complexities of being a Greek-Australian woman at the time, and looks at the complexities of negotiating ethnicity, sexuality and the translation of power – not unlike Lee during that period.

Their work is paired with a piece from Lesley Goldacre’s Rites of Passage series 2 (1993), and a grid of four works from Ruth Maddison’s Women over sixty series (1991) – all black and white, conservatively framed, and intimate in scale, and yet these four women artists working in photo media ushered in an important chapter of social commentary.

The exhibition then starts to open up in scale, punch and technique. The next gallery space presents works from Brisbane artist Maree Cunnington’s Secretions series (1997), works that also play on bodily fluids; the fantastic punchy work Reproduction: Blondes (1986) by Janina Green alongside Jay Younger’s I dream of you at night from her Tragic Romance series (1986), to the more expansive Pet Thang (1991) by Tracey Moffatt, which juxtaposes a lamb with the artist’s body – ‘the female domesticated, traded, exploited, murdered’.

Goddard said that the title of the exhibition, Dark Rooms, is a translation of the term Camera Obscura, and reveals artworks that are acutely aware of the way the lens can empower or reduce the subject – the camera as a weapon. ‘Photographs made by many women artists during this period differed in a significant aspect. They took authorial agency into their own hand,’ she said.

Moffatt’s Pet Thang series was produced two years after one of her most renowned works – the self-portrait Something More (1989), also featured in this exhibition. It sits with a group of artists who dive a little deeper through the self-portrait genre, including Julie Rrap, Anne Zahaika, Fiona Foley and Destiny Deacon.

Installation view Dark Rooms: Women Directing the Lens 1978 – 98, Griffith University Art Museum; Left Tracey Moffatt, right Julie Rrap; photo Artshub.

Deacon wrote at the time (1994): ‘Photography is white people’s invention. Lots of things seem really technical … Plus it’s expensive. Plus I think it’s not fair that only white people should be the only ones who can do “photography”. I’ve started taking the sort of pictures I do because I can’t paint … and then I discovered it was a good way of expressing some feelings that lurk inside.’

It captures a feeling that I am sure many of these women felt working between 1978 – 1998. It is impossible to speak about all the works in this exhibition with the kind of palpable impact they had – both at their making, and as they stand in the gallery today.

In short, this is an exhibition worthy of the serious curatorial lens it has been given. Its place within a university gallery not only supports the importance of these collections as a learning tool, but also salutes the role that experimentation and boundary pushing must play – and continue to play.

Rating: 4 ½ stars ★★★★☆

Dark Rooms: Women Directing the Lens 1978 – 98

Griffith University Art Museum, 226 Grey Street, South Bank, Brisbane

12 July — 25 August 2018

Artists: Maree Cunnington, Destiny Deacon, Linda Dement, Marian Drew, Bonita Ely, Fiona Foley, Elizabeth Gertsakis, Lesley Goldacre, Janina Green, Fiona Hall, Leah King-Smith, Lindy Lee, Anne MacDonald, Ruth Maddison, Wendy Mills, Tracey Moffatt, Jill Orr, Nat Paton, Eugenia Raskopoulos, Julie Rrap, Robyn Stacey, VNS Matrix (Virginia Barratt, Francesca Da Rimini, Julianne Pierce, Josephine Starrs), Heather Winter, Jay Younger, Anne Zahalka.