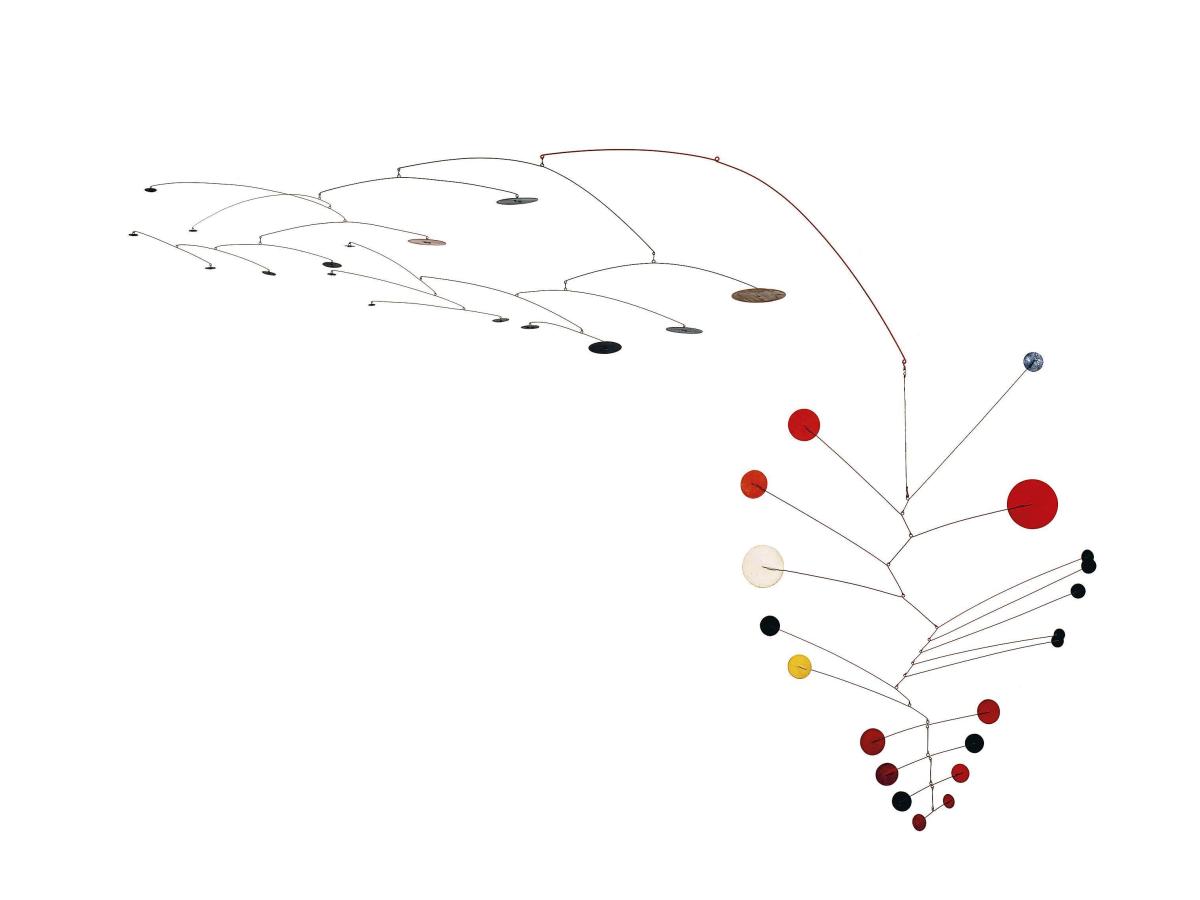

Alexander Calder, Gamma (1947). Painted sheet metal and steel wire. 147.3 x 213.3 x 91.4 cm. Collection of Jon Shirley © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Copyright Agency, Australia.

On entering the Alexander Calder exhibition, one is drawn into a world that celebrates the notion of play: that precious experience once relegated to childhood is now understood to be just as vital for adults’ emotional wellbeing and intellectual development. Born into an artistic family – his mother a painter and father and grandfather sculptors – Calder was encouraged to create, tinker and explore from an early age. This formative time in the artist’s early life set him on a trajectory of creative experimentation that was to become a lifelong obsession.

Developed by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in collaboration with the Calder Foundation and NGV, the exhibition showcases around 100 works of this influential 20th-century American modernist. Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor is currently showing at the NGV International in Melbourne and includes sculpture, drawing, painting, book illustrations, fabric design and jewellery from both private and public collections.

Well-designed exhibition spaces successfully showcase the artist’s work as the viewer zigzags between brightly lit, white-walled rooms to follow the journey of Calder’s artistic development from childhood creations through to his famed mobiles and later large-scale public works. Plinths, cantilevered platforms, window spaces in walls and discreet display cases both showcase and echo the diversity of an artist who democratised art by working across many mediums, often with non-precious materials.

Early works in brass sheet such as Dog (1909) and Duck (1909) are small sculptural pieces that an 11-year-old Calder made as presents for his parents; they foreshadow the skill in spatial thinking and design ability that was to become a trademark of his art making. Carefully positioned spot lighting creates shadows that form an important extension to these sculptural works. In the case of his kinaesthetic sculptures, the shadows capture something of the changing nature of these sculptural pieces as they move.

Works such as Toilet Paper Holder (1940) and Scissor Guard (c. 1940), made from brass wire and sheet metal, join a sense of fun with utility while jewellery pieces such as Fish Brooch (1940) and Goat Brooch (1943), made from silver and steel wire, also echo this humour.

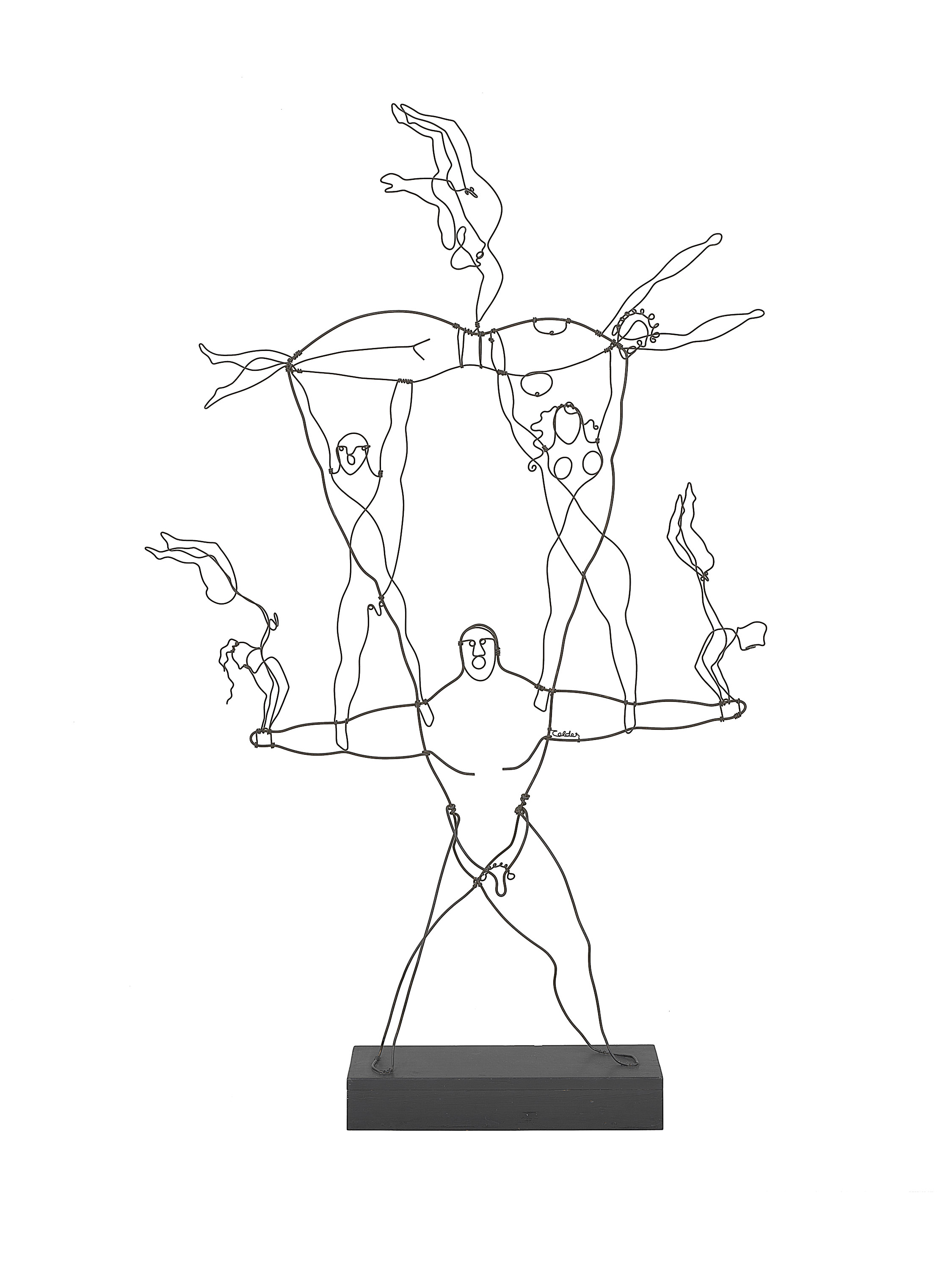

Alexander Calder, The Brass Family (1929). Brass wire and painted wood. 170.2 × 104.5 × 22.5 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of the artist. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Copyright Agency, Australia.

It was Calder’s fascination with the circus, however, that caught the attention of Paris’ artistic community during his first stint in France in the late 1920s. Forming friendships with avant-garde artists such as Fernand Leger, Jean Arp and Marcel Duchamp was to have a lasting legacy on the young Calder and his work. Le Grand Cirque Calder (1927), an example of early performance art shown largely to family and friends has been captured by filmmakers like Jean Painlevé and is included in the exhibition, transferred from 16mm film to a digital file. This miniature circus fashioned from wire, string, cork, cloth and other found objects became the basis for Calder’s wire sculptures in which he used single pieces of wire to ‘draw in space’; these line forms gained a three dimensionality as can be seen in works such as The Brass Family (1929) featuring acrobats as well as his portrait works.

Showcased throughout the exhibition are examples of Calder’s famed ‘mobile’, the term a French pun coined by Marcel Duchamp meaning ‘motion’ and ‘motive’. A visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio changed the course of Calder’s practice and triggered an interest in kinaesthetic abstraction. Loosely influenced by the cosmos and elements of nature, Calder combined his background in both mechanical engineering and art to design kinetic works; some using motors, such as Half-circle, Quarter-circle and Sphere (1932), made from metal, wood, motor and paint. Calder’s later mobiles like Jacaranda (1949), made from heavy gauge wire and steel, rely purely on air currents, balance and tension to move – a striking example of his mastery between balance and form.

In contrast, Calder’s static sculptures like Little Spider (1940), which were named ‘stabile’ by Jean Arp to differentiate them from the mobile, reflect the artist’s experimentation with self-supporting, static art. Black Beast (1940) is an example of a large stabile and a forerunner to Calder’s ‘agrandissements,’ or large scale public sculptures of the 1950s and 1960s which were installed in public spaces.

This is an extensive exhibition that doesn’t feel too large. The adjacent children’s gallery features hands-on and multimedia activities for children to create their own Calderesque pieces while support material such as didactic panels, text labels for kids, and film along with catalogues placed in the gallery spaces reflect a mindfully developed exhibition that provides a good overview of the artist’s work and development. People with mobility difficulty however may find navigating some of the gallery spaces, when crowded, a little challenging.

An important exhibition that artfully captures Calder’s humour and joy of creating.

4 stars ★★★★

Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor 5 April – 4 August 2019 NGV International Tickets $10-22