Tindo Utpurndee at Adelaide Fringe; photo by Claude Raschella.

On the forecourt of the South Australian Museum, as the sun sets behind buildings of glass and sandstone and aeroplanes etch brilliant vapour trails across the darkening sky, the Kaurna people gather. In language, the young people honour their grandmothers, mothers and aunties; their uncles, fathers and grandfathers. They acknowledge their millennia-old connection to Tarntanya (red kangaroo place), as the Adelaide plains were known before colonisation; they celebrate resilience and survival.

Tindo Utpurndee, the sunset ceremony, marked the opening of this year’s Adelaide Fringe. There is a potency to such events that goes beyond art; like the recent Siren Song at Perth Festival, which saw Noongar voices echoing down St Georges Terrace at dusk on the Festival’s opening night, hearing such words celebrated in the city that displaced their culture and denied their agency powerfully evokes an awareness of deep time; of 60,000 years of lived experience, of thousands of generations of shared wisdom. Being witness to such gatherings is a privilege, and deeply moving.

Vast crowds flocked to the Adelaide Fringe’s opening night street party, and while the traditional Fringe Parade was not held this year due to interruptions caused by street works and the laying of new tram tracks on North Terrace and King William Road, the attendant throng seemed more than entertained by the alternative provided, the Parade of Light.

Among the many striking projections – star-scapes projected on the façade of the Art Gallery of South Australia, sandstone pillars appearing to spin like brightly coloured barber poles – the highlight is undoubtedly Borealis, created by artist Dan Acher. Utilising lasers and haze machines, the work recreates the Northern Lights above the Museum lawn; swirls of purple and green dancing and swirling overhead. Coupled with a moody soundscape by OXSA, the overall effect is genuinely enchanting.

Now in its 57th year, Adelaide Fringe draws huge crowds to events across the city and suburbs for its 31 days of arts and entertainment. Attempting to provide a snapshot of this juggernaut of cultural activity, to convey a sense of the energy which crackles through streets, parklands, and Spiegeltents during this time, is almost impossible. Nonetheless, I’ll try.

THURSDAY 15 FEBRUARY

After an early start and three hours of radio, I race to Tullamarine Airport, fly to Adelaide, check into my hotel and grab a half-hour nap before catching the tram out towards Hindmarsh, and Holden Street Theatres.

Large numbers of people all seem to be walking in the same direction. I’m disappointed to discover they’re heading to Coopers Stadium, the football ground adjacent to Holden Street, instead of congregating for art.

Luckily the three UK productions I’m about to see – all hits of the Edinburgh Fringe – are well-attended, though the audience shrinks a little with each passing hour; a shame, as the night’s 9pm performance, Love Letters to the Public Transport System, is my pick of the bunch.

Borders

Photo: Steve Ullathorne

Written by Henry Naylor and directed by Michael Cabot (with Louise Skaaning), Borders is a classic Adelaide Fringe two-hander: the only props are a pair of stools which are occasionally upturned and rocked upon to represent passage on a boat, or laid flat and crouched behind as the actors emote.

Two slowly converging narratives unfold over an hour. The first is the story of Nameless (Avital Lvova), a young Syrian artist who fights the Asaad regime with graffiti after its secret police murder her father. She refuses to give us her name; her silence is the only power she has left.

We also encounter Sebastian (Graham O’Mara), a privileged, promising English photo-journalist whose early encounter with fame reroutes his career towards facile celebrity portraits and a blunting of ambition and purpose. He is a disappointment to his mentor, and to himself.

Borders humanises the Syrian crisis, which to date has seen more than 11 million people seeking asylum in neighbouring countries, though it is less focused on the process of seeking asylum and more upon detailing the conditions which force people to flee their homes.

Performances are focused, truthful and intense; dialogue less so. After a character throws themselves to the ground we don’t need the script to tell us they throw themselves to the ground. The text is sometimes overwrought and, in the case of Sebastian’s narrative especially, reliant on cliché. Conversely, some lines thrum with power, like an arrow hitting the bullseye, such as when Nameless, in a brief and complex moment of passion with a persistent oud player, cries out, ‘This isn’t sex. It’s defiance!’

It’s clear that Naylor writes with insight and intelligence, though his decision to compare the life of a man all at sea with the experiences of someone drowning at sea feels glib, even insulting. Excising the character of Sebastian and focusing more specifically on Nameless and her peers would render this a deeper, more compelling drama.

3 stars

Flesh & Bone

If Shakespeare was a writer for the TV series Shameless he’d probably come up with something not dissimilar to this bawdy, fast-paced, physical, and engaging slice of East End life, which plays with language and our perceptions in equal measure.

‘What a piece of work is a man,’ begins our knockabout Everyman, Tel (Elliot Warren, the play’s writer and co-director) before sliding into a poetic, colourful, expletive-laden vernacular.

Tel shares a rat-infested flat in a London housing estate with his girlfriend Kel (co-director Olivia Brady) and her grandfather (Nick T. Frost). Tel’s brother Reiss (Michael Jinks) and local drug dealer Jamal (Alessandro Babaloa) are also on the scene. They’re ‘the dregs that stay snared and never get out,’ trapped on the estate by poverty and society’s contempt for them, their lives brutal and passionate in equal measure.

The contrast between Shakespearean phrases and rhymes and contemporary language parallels the divisions between public façade and private pain experienced by the characters: Jamal’s performative masculinity and secret anxieties, Reiss’ fear of rejection if he reveals the truth about himself: ‘Why can’t a fella be a geezer and fabulous at the same time?’ he asks plaintively.

Warren’s writing doesn’t give as much nuance to all the characters – Kel in particularly feels less than fully formed – and a final monologue for Tel feels laboured. The play’s ending feels somewhat abrupt, as if the author had been forced to quickly conclude what could easily – and deservedly – be a longer piece.

Warren and Brady’s direction is assured, balancing tonal shifts and successfully generating both comedy and compassion. They also bring a compelling physicality to proceedings, such as a dynamically choreographed pub fight and an in-your-face birthing sequence involving audience members and a soccer ball. Performances are excellent throughout.

Though not for the easily offended, Flesh & Bone is bursting with heart and cocky charm. Definitely recommended.

3 ½ stars

Love Letters to the Public Transport System

Love, fate, heartbreak, buses, trains and the Tube; this elegant, minimal, moving and disarming one-woman show celebrates the often-overlooked intersection of the public and the personal.

Written and performed by Molly Taylor, Love Letters to the Public Transport System focuses on everyday events which nonetheless have the power to change lives: a bus driver who genuinely cares for his passengers; the chance encounter in a London pub that sets your feet on a new path.

Tam dreams of writing the perfect one-man play. Carrying a confiscated stereo system, its wires dangling, Margaret is inconsolable. Molly is obsessed with finding and thanking the bus and train drivers whose incidental presence helped change her life.

Shifting her tone and body language to indicate shifts in narrative, Taylor has no trouble holding our attention for the duration of this one-hour performance. The result is a genuinely transporting work about the joys of public transport, and a true story about being brought back to life.

Touching without being earnest, truthful and perfectly pitched, Love Letters to the Public Transport System is an unassuming gem of a show. Unmissable.

4 stars

FRIDAY 16 FEBRUARY

The official opening of Fringe was held this year at Government House; a surreal setting for an event ripe with irreverence, but indicative of the Fringe’s cultural significance. The opening saw protocol thrown to the winds as Le Gateau Chocolat and Jonny Woo entertained the crowd in their own inimitable style, before formal proceedings got underway. After speeches from dignitaries, including His Excellency the Honourable Hieu Van Le AC, Premier and Minister for the Arts Jay Weatherill, and Fringe Director and CEO Heather Croall, the assembled crowd of arts workers, VIPs and the odd arts journalist, strolled across the manicured lawns and out into the street for the sunset ceremony, Tindo Utpurndee (see above). Thereafter, the feast of Fringe performances continued.

Glittery Clittery: A ConSENSUAL Party

The Fringe Wives Club’s Glittery Clittery is a seriously playful celebration of consent, wit, and comedy. It begins with three mysterious, hooded figures welcoming us to ‘the inner sanctum of the Clitterati’ before launching into a feminist hoedown and hootenanny performed with vim and vigour by Tessa Waters, Rowena Hutson and Victoria Falconer.

We learn about the sexist history of women not having pockets (although endearingly we’re also requested not to fact-check the story’s history), hear about ‘Annoying Michael,’ who ‘only hurts you ‘cause he likes you’ (a powerful showcase of the Fringe Wives’ ability to utilise music to present a potent political message) and play Lagoon of Mystery, a game show that generates much of its laughs from audience members’ inability to correctly name parts of the female anatomy – as well as generating a few new names along the way.

Not every element of the show hits its mark – the ‘Lady Boner’ song doesn’t quite land, while a speech delivered late in the piece is a trifle laboured – but the trio’s combination of politics, physical comedy and song is endearing and often hilarious. As the Fringe Wives Club demonstrate, consent is really hot – so too is sex-positive feminist cabaret. More please.

4 stars

SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY

When you’re a visiting arts writer, it’s not unusual to start the day by breakfasting with a local theatre critic or lunching with the festival team – being serenaded over lunch by local cabaret legend Hans, however, is less expected but absolutely recommended. Then it’s on with the show.

The Displaced

Photo credit: Rudi Deco Photography

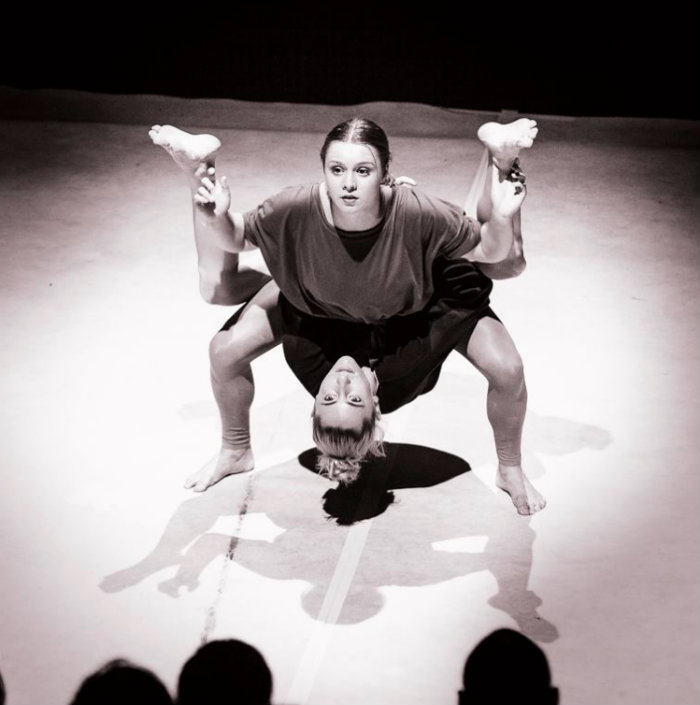

For me, the highlight of Adelaide Fringe this year was a new, experimental circus work by local company Time in Space Circus. Predominantly comprised of Adelaide artists trained at local circus school Cirkidz, together with one member from Canberra, these seven acrobats are intent on bringing a fresh aesthetic to the circus arts while also deconstructing the familiar flow of tricks and routines.

An acrobat who struggles to get up from the floor; a would-be juggler whose hand jerks compulsively away from the ball he tries to catch; a performer who rewards himself for each backflip he performs by donning bulky layers of clothing and other items before launching himself into the air again, each time challenging himself by setting the bar higher. Quiet attention to costume and presentation – performers are only half dressed, or dressed in rags, while their expressions remain neutral throughout – further subvert the art form’s traditions.

Just as the children in the crowd grow restless the troupe explode into dynamic group routines – tumbling, leaping, a single handstand atop a colleague’s head.

Throughout the performance there’s a conscious sense of avoiding easy crowd-pleasing tricks and a refreshing focus on the ensemble – members remain quietly on stage during one another’s routines.

The company’s aesthetic is striking and it’s clear there’s a fierce intelligence at play here, as well as skill and ambition aplenty. An excellent production from talented artists whose attention to detail is reflected in every aspect of the show, including original songs and music. I can’t wait to see what they do next.

4 stars

Courtney Act – Under the Covers

Drag queen Courtney Act (Shane Jenek) was recently crowned the winner of Celebrity Big Brother in the UK, and made sure we know it, with constant references to her time on the program peppered throughout this production.

Spending a month locked in the Big Brother house meant she had little time to rehearse this show, and it showed: Act regularly referred to a script placed at stage left, even while singing ‘Vegan’ (a parody song set to the tune of Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’). Had this been billed as a preview, such poor preparation would not warrant comment, but as punters were being charged full price for the privilege of seeing Ms Act stumble over her words and forget her show structure (as well as the ending of her own songs) her ill-preparedness came across as unprofessional and inappropriate.

Not that her fans seemed to mind, at least when they stopped talking among themselves and paid attention to the performer they’d paid to see.

Great cover versions bring new light to old favourites and uncover fresh depths to familiar songs. Great drag performers subvert our preconceived notions of gender and speak uncomfortable truths freely. Under the Covers did neither. An underwhelming production from one of this year’s Fringe Ambassadors – hopefully her ability to promote the festival internationally is stronger than this show.

2 stars

Cirque Alfonse – Tabarnak

Among French-Canadians, the best swear words refer to religion, according to the helpful French-Canadian couple sitting next to me on Saturday night. The latest production from Québécois Cirque Alfonse embodies this sensibility, opening with and satirising a modern religion – sport – before throwing in a drunken priest and a levitating stained-glass window.

Roller skating routines, tap dancing in bowling shoes, whip-cracking, censer-swinging, pew-inverting and gleefully acrobatic bell-ringing – there’s much here to please the eye. Beneath the surface-level entertainment, a deeper theme emerges: performers scramble upwards as if reaching for heaven, bodies shoot through splayed legs as if referencing the virgin birth before being dunked in a giant baptismal font. No sacred cows are spared, and yet there’s not enough bite in proceedings to fully satisfy the discerning circus palate.

Going up an hour late (due to a previous show in the same venue disrupting proceedings) clearly put the performers off their mark – one acrobat visibly limped offstage after an awkward landing, and for several minutes afterwards there was a wobbliness to his compatriot’s routines; a lack of focus that resulted in several acts not quite landing, and later a clear attempt to quickly restructure aspects of the show. Acrobats are only human, but the flaws in this production go deeper than just a bad night.

Possibly something central to the work has been lost in translation, but it feels more like a case of artistic opacity; a production created out of necessity rather than artistic inspiration. Tabarnak is inventive, with some genuinely impressive routines, yet the production lacks heart; it’s a show one watches rather than feels. Nor is it helped by being staged in too small a venue, resulting in a key piece of apparatus being partially obscured in the wings during what should be a thrilling climax.

According to the company’s website, ‘TABARNAK … was once a rebellious cry against authority and is now a rather banal expression of pain, anger or astonishment’. While not quite banal, Tabarnak fails to reach the heights of truly great circus; it entertains, but it’s far from memorable.

3 ½ stars

SUNDAY 18 FEBRUARY

The final day of the opening weekend was overcast and threatening rain. Were it not for the crowds seeing shows before midday I’d almost feel like I was already home in Melbourne. But there’s no time to ponder the weather: more art adventures await.

The Secret Life of Suitcases

Image supplied

Programmed as part of Grounded, a new children’s precinct at the Fringe this year, The Secret Life of Suitcases is a winsome and enchanting production that will delight children and their adults in equal measure.

Lanky Larry is busy. Very busy. Too busy for things like coffee with his workmates or a lunchtime walk in the park. Definitely too busy to have fun, or for cosmic understanding. So when a remarkable flying suitcase with his name on it turns up in his office one day, he’s more than a bit perturbed.

Two puppeteers (Ailie Cohen and Samuel Jameson) present Larry’s adventures, their brown suits initially echoing his. As his adventures transport him first to a park outdoors, then to the beach, and eventually to outer space, their costumes change to initially echo, then become part of Larry’s world – with a cardboard shark fin moved across an ocean-blue t-shirt one of the many delightful design touches that make this production as inventive as it is enchanting.

I cried while watching The Secret Life of Suitcases – tears of delight, at the artistry on display, and tears of sadness, provoked by the production’s quiet warnings about a world permanently at war. Where’s a magical suitcase when you need one?

4 stars

Casus Circus – Driftwood

Photo: Angus Stewart

Watching a performance, regardless of its genre, one sometimes gets a sense of artists going through the motions, as if they’re committed to but not passionate about the performance. That was my impression while watching Casus Circus’ Driftwood at Gluttony this year. It’s not that it’s a bad show, or even that the performers weren’t actually committed, just that there was an indefinable something missing.

Writing this review the following day, I remembered something a friend in the industry once told me about circus being an art that’s ‘written on the body’, and it occurred to me to compare the list of performers I saw with the list of artists who originated the work. They’re completely different.

What I saw was effectively a circus covers band; a sub-par translation of the original physical idiom; a photocopy. It’s far from a bad production, but the magic is missing, a fact which all the fixed smiles and skillfully executed routines can’t quite conceal.

Nonetheless, there are moments of beauty here: the group work and interlocking of bodies delights; the recurring use of what the small child beside me referred in whispers as ‘the cheeky light’ intrigues; traditional gender roles are challenged, especially by strongwoman Spenser Inwood; and it’s always a pleasure to see different body types and heights represented in circus. Conversely, the choice of some distinctly MOR music numbers on the soundtrack, and a few extended movement sequences that feel more like padding rather than integral, further detract from the production.

The general public may be entertained by this particular iteration of Driftwood, but if you’re a circus devotee, I recommend Time in Space’s The Displaced instead.

3 stars

Adelaide Fringe

adelaidefringe.com.au

16 February – 18 March 2018

Richard Watts visited Adelaide as a guest of the Adelaide Fringe.