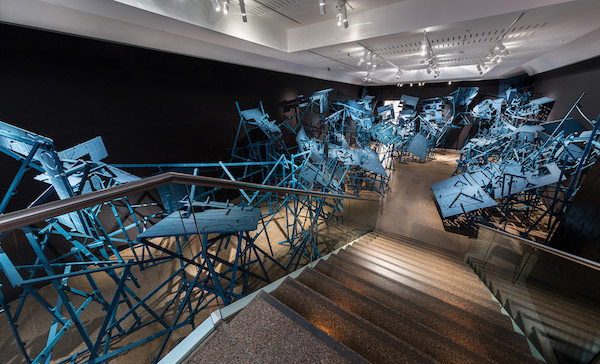

Lindy Lee, The Life of Stars (2015), installation view Art Gallery of South Australia, 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art; fabricated by UAP; Photo Saul Steed; courtesy the artist and Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney.

The title for the 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Divided Worlds, immediately conjures a tension; it presupposes a split, polar thinking and values – a kind of bubbling darkness that is rupturing from within.

But at first glance I wouldn’t describe this exhibition as dark, or particularly political or socially uncomfortable. Disparate, yes, but the trigger points in Divided Worlds are more subtle than sledge hammer.

The exhibition’s curator, Erica Green (Director, Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art) turned to another word to shed a little more light on her theme, describing it is a ‘prism’.

Green explained: ‘Each of its surfaces absorbing human values, cultural meanings and all manner of disparate things, which are then gathered and concentrated within the prism’s three-dimensional centre, a synthesized conglomerate, through which light shines.’

Put simply, opposing things in unison can shine like a gem.

But does this analogy fit the delivery of Green’s Divided Worlds? If we were to look at Lindy Lee’s signature sculpture, The Life of Stars (2015, pictured top), placed outside the Art Gallery of South Australia and along Adelaide’s Northern Terrace, the answer would have to be yes.

Lee’s work becomes illuminated at night, touching everything in its reach with a dappled magic, transferring a sense of awe to the everyday. It is a sure highlight of this exhibition, and acts as a kind of beacon of what we might expect inside.

It’s alchemy-like shift between being viewed in the day and at night, resonates in a very literal sense with walking into the galleries; the upper levels are bathed in light while the lower galleries, with their black walls, almost incite an oppressive contemplation.

This dramatic shift becomes a central theme in this year’s Biennial. Green was quick to comment in her opening speech that ‘we’re living in troubled times.’ For the purposes of this exhibition, she added, ‘difference is the natural order – it has always been around and is part of who we are and what we do. If civilisation is to move forward, then we must recognise those differences.’

Co-director of the Adelaide Festival, Neal Armfield added to her thesis: ‘The power of great art is to tell a truth, and surrounded as we are in a world where truth is so manipulated, so distorted and so denied – in the most astonishing ways that threaten our existence – the power of art is to force that reality through.’

So how real does this Biennial look, feel?

Installation view Tamara Dean’s work at the Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide Botanic Gardens; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed.

How cohesion nullifies a theme’s expectations

On first view of this exhibition I felt uneasy about many of the couplings of works, for example Tim Horn’s steroid-sized jewels with their blown glass pearls and silver filigree foliage adjacent to the seriously non-bling, highly researched, stripped back video installation by Julie Gogh.

Installation view Nike Savvas and Ken Sisters, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed.

Or Nike Savvas’ shimmering kinetic silver installation with the highly colourful triptych by Wynne Prize winners, the Ken Sisters; or Patricia Piccinini’s post-human considerations transitioning to a body-is-everything, body-as-archive video by the collective Barbara Cleveland, to Roy Ananda’s Dungeons and Dragon’s inspired site of construction and fantasy transitioning to Lindy Lee luminous golden Zen form that is anything but play.

Alarms sound. Overlaying a theme that begs us to find connections.

But Green makes us work for these, offering a more erratic thread across the exhibition that can only be observed by stepping back and considering its entirety, rather than an intuitive flow as we move through it.

The real successes are found in the reach across venues. A good example is Christian Thompson’s sound work in the Palm Garden at Adelaide Botanic Gardens and how it connects with his suite of photographic works at the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, where the artist’s eyes reflect the Palm House.

At the hands of Green, this theme of difference then might, in fact, gazump itself. It kind of nullifies expectations of cohesion, and in that is appropriate grounds for a survey exhibition that looks at the zeitgeist of making now, which could only ever be ‘divided’. It strikes me as a flaw that works brilliantly.

Divided thoughts – divided highlights

Divided Worlds brings together 30 Australian artists and collectives to present new work and amplify the role Australian art is playing in asking what we are, who we are, and where we are heading, summarised Nick Mitzevich, Director AGSA.

Divided Worlds attracted $1.2 million in donations from private and corporate benefactors nationally, to assist the production of that new work for this exhibition, 37% up on the 2016 event.

Heartening across those commissions is the stretch of media without a sense of hierarchy, something AGSA has always done well, but also the reach of artists across generations and stages in their careers. This is a credit to Green’s scope.

Installation view Claire Healy and Sean Cordero’s We hunt Mammoth (2015) at Art Gallery of South Australia; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed.

A number of works in the exhibition come from existing series that have been extended, reworked or expanded, such as the work of Emily Floyd and Khalid Sabsabi at Samstag, Maria Fernanda Cardoso’s work at JamFactory, Tim Horn and Claire Healy and Sean Cordero’s work at the AGSA. There is a familiarity to this show.

Among the highlights across the exhibition are Tamara Dean’s arresting commissioned photo series In Our Nature at the Museum of Economic Botany, and at AGSA her Stream of Consciousness. Kirsten Coelho’s ceramic installation, Transfigured Night (2017) at JamFactory, and Tim Edwards’ glass vessels that mess with our perception.

Claire Healy and Sean Cordero’s epic deconstruction of a Toyota car at AGSA and Roy Ananda’s Thin walls between dimension (2018) also at AGSA both offer that spectacular punch of a large-scale work we expect of these festival exhibitions, and deliver.

Installation view of Roy Ananda’s Dungeon and Dragon’s inspired work at Art Gallery of South Australila; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed

Picking up the threads and themes across this exhibition, we can unpack Divided Worlds as a site of conflict where the human-nature relationship has broken down.

Dean celebrates our relationship with nature as her sensual nudes seemingly meld into the flora and season in the Botanic Gardens, as does Amos Gebhardt’s monumental four-screen video work at AGSA, Evanescence (2018) – the horizon lines of four landscapes meeting and a connected mass of choreographed bodies speaks to the timelessness of body and land.

Amos Gebhardt’s four channel video work at Art Gallery of South Australia; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed

Dean’s second piece however is her pièce de résistance. Working with David Kirkpatrick on a soundscape and scent designer Ainslie Walker to create a pungent earthy dimension, visitors enter a darkened space where the image of a young male is caught mid-flight as he leaps into the unknown – he’s reflected in a pool of water that the viewer can only see at a given angle.

This sense of another dimension plays across the exhibition, at times subtle – as with Dean’s work that that moves across the 2-D image to other dimensions of sound and smell – to the more literal play with perception and deception in Tim Edward’s work, which punches the drawn vessel into a dimensional object.

With his vessels, Edwards carves away the black outer layer to reveal the clear or coloured glass underneath, reverse of the drawn black line on a white page.

Suite of Tim Edward’s glass vessels at Art Gallery of South Austraia; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed

Ananda and Pip & Pop (AKA Tanya Schultz) also play with a kind of division in their grasp on the real and imagined in a dimensional way – one using construction material and the other sugar to construct worlds of fantasy and seduction.

With a different tone, Kirsten Coelho could also join the list of artists who throw our perceptions into another dimension.

Her sublime installation of ceramics seemingly levitate in a blackened gallery at the JamFactory, an illuminated zip that runs across the space. Sitting in clusters on an over-height pedestal, the viewer looks into these vessels with a bodily engagement, rather than the traditional gaze down onto a vessel. It shifts the functional into the ethereal.

Installation view of Kirsten Coelho’s ceramic pieces at JamFactory; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Saul Steed.

While Coelho overlays a story of the Drover’s Wife on this suite of works, for me the nostalgia lies instead with Giorgio Morandi, or the clustered vernacular of British sculptor Tony Cragg, moving this work beyond its craft associations. Perhaps these traditionally divided worlds become a little closer in this Biennial.

Painting is also given a serious nod in this survey – more traditionally with the Ken Sisters whose paintings depict their Anangu Pitjantjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands with a timeless energy, while John R Walker has immersed himself in the wilderness of the Flinders Rangers and Burra where time also slides between this ancient land and the detritus of human impact.

Installation view of John R Walker’s paintings at Art Gallery of South Australia; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo Artshub, courtesy the artist and Utopia Gallery, Sydney.

Khaled Sabsabi offers an alternative take on the body and landscape through his 99 Names, hand-painted photographs that fuse Beirut’s war-ravaged landscape with an internalised spiritualism, referencing the Ninety-Nine Most Beautiful Names of Allah – leaving the viewer to bridge the gaps and apply the lessons.

Sabsabi’s series has been created over a decade from 2007-2017, and he says it is an ongoing act of healing. The installation at Samstag feels modest beside Vernon Ah Khee’s bold political sloganeering, visual a bold contrast, but conceptually an interesting comment on the amplification of topics current. It offers a journey along a wall, that abruptly ends at a corner – a transition point. Like Coelho’s work at JamFactory, the sensitive installation of Sabsabi’s work extends its conversation to another world.

Installation view of Khalad Sabsabi (left) and Vernon Ah Khee’s work at Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; Photo ArtsHub

Like Ananda, self-taught painter Lisa Adams is also a gem in this show, introducing a fresh voice to this Australian conversation. Her work is interesting in relation to Archibald winning Louise Hearman, both artists amplifying the psychological.

Adams’ hyper real paintings grapple with fear via dreamlike theatrics, while Hearman’s severed heads hover towards the viewer – not unlike a transition to scene in Batman. She has an incredible capacity to connect through her paintings; to have an impact on us through something that is compelling and non verbal, but resonant and familiar.

Louise Hearman Untitled #1502, presented at Art Gallery of South Australia; 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds; courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery and Milani Gallery.

The archive is also another thread that Green calls on to define the Divided Worlds. Julie Gogh, Patrick Pound, Angelica Mesiti and Barbara Cleveland all use the archive as a central device – whether documenting the body as a living archive or a museological record of history.

In a more oblique way, Healy and Cordero fit here too, with their reboot of the process of archiving with a contemporary inflection to speak about obsolescence in their installation We hunt Mammoth.

As one dives deeper into thinking about this exhibition – and what it delivers – one starts to understand that the word ‘division’ can be successfully applied to anything.

Perhaps this is an incredibly smart choice on behalf of Green, to leave the exhibition wide enough for collective association but charged enough to beckon us to consider the state of the world now.

Rating 3.5 out of 5

2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds

2 March – 3 June 2018

Venues: Art Gallery of South Australia, Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, JamFactory, Museum of Economic Botany and Botanic Gardens

North Terrace, Adelaide

ArtsHub was a guest of the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art