Eija-Liisa Ahtila Potentiality for Love (2018), Installation view AGNSW 21st Biennale of Sydney; commissioned by Serlachius Museums with support form the Biennale of Sydney, Frame Contemporary Art Finland, Alfred Kordelin Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery; photo ArtsHub.

Curated by Tokyo-based Mami Kataoka – one might observe that, on appearance, this year’s Biennale of Sydney has a softer, more sensitive touch.

It is not surprising when you look at Kataoka’s theme, which largely rests on the concept of Wuxing. According to Chinese philosophy, everything in this world is made up of Wuxing – the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal and water – each evolving to the formation of the next.

This is more obvious in some works than others. For example, Kate Newby’s “wind chime” hanging in the vortex between floors at the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) or Roy Wiggan’s constructions that call on the metaphysical and oceanic phenomena.

Turning to earth can be observed in Geng Xue single-channel video, The Poetry of Michelangelo (2015) at Artspace, where the artist brings life to a figure in clay, while at Cockatoo Island Anya Gallaccio giant 3D printer explores the process of transformation and decay using clay. And you can’t dismiss the narrative of earth in George Tjungurrayi’s reflections on the desert and Sam Falls’ canvases that randomly use organic material, both exhibited at Carriageworks.

Geng Xu The Poetry of Michelangelo (2015), video still; 19 mins, courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Contemporary Chinese Art Collection Sydney; photo Artshub.

What Kataoka has managed to do beautifully is string these ideas across works and across venues. There is not the kind of stereotype pummel that these spectacular festival exhibitions use like a formula to muscle their way into the press, with the mantra that big, bold and provocative equals good.

Kataoka’s 21st Biennale of Sydney proves that a soft voice can speak just as loud. There is incredible strength in her subtlety.

Installation view of George Tjungurrayi’s painting at Carriageworks for 21st Biennale of Sydney; Photo artshub

Delivering equilibrium and engagement

Kataoka abridges her boarder theme of SUPERPOSITION: Equilibrium and Engagement, with the simple definition: It refers to ‘an overlapping situation’ where things exist in duality, but simultaneously. Artists today work across locations, across ideas and across histories, responding to the world around them, so the panoramic view they offer collectively delivers a natural equilibrium.

And surprisingly this exhibition – especially given its scale – is in balance. No one medium dominates, no one venue dominates, there’s no placard politics that goes unchecked, or subtlety that is coaxed into higher volume.

A surprise was the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), where Kataoka placed a number of minimal pieces, large-scale works by Tom Nicholson, Jacob Kikegaard, Liza Lou, Maria Taniguchi, and Nicole Wong.

Jacob Kirkegaard Through the wall (2013) installation view MCA for 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo Artshub

They sit in a minimalist conversation with Prabhavathi Meppayil and Lil Dujourie’s work at the AGNSW, Tanya Goel’s ultramarine pigment on the wall of Artspace, Index (2015), Koji Ryui’s glass installation and Jasmin Smith’s ceramic installation at Cockatoo Island.

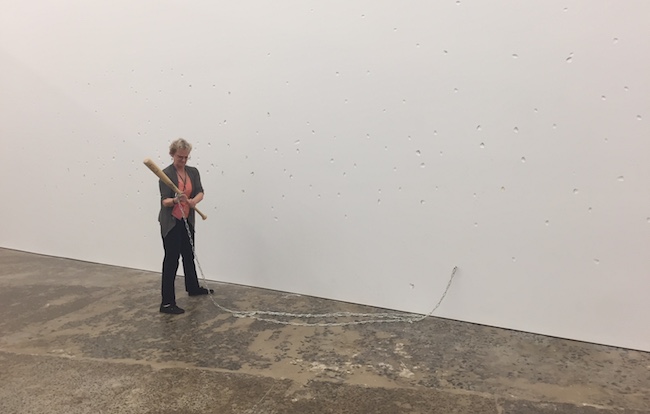

There are other’s less obvious, such as Marco Fusinato’s Constellations (2015) at Carriageworks which looks at the transference of energy. The viewer arms themselves with a baseball bat and takes a mighty wallop at a pristine white wall activating an almighty sound reaction. It is an ‘examination of human action and decision making’.

As a Sydney curator remarked to me at the opening, Kataoka pays a nod to the white cube through these works.

Marco Fusinato Constellations (2015) at Carriageworks, 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo ArtsHub

Of course, there are the big punch, big signature moments in Kataoka’s exhibition. The noise surrounding Ai Weiwei’s inclusion has been amped up to maximum – a condition that seems to follow his movements around the globe. But does the work deliver?

Kataoka has placed Law of the Journey, Ai’s 60-metre rubber inflatable raft filled with more than 250 figures, at Cockatoo Island, a venue with a history of shipbuilding and immigration.

Whether intentional or not, there was also a strong reminder of the 2014 Biennial of Sydney boycott, when exhibiting artists protested over principal sponsor Transfield Holding’s links to offshore detention centres for refugee processing.

Ai Weiwei Law of the Journey (2017) installation view at Cockatoo Island for 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo ArtsHub

Conceptually the work fits – and Cocktaoo Island’s Turbine Hall certainly needs an artwork of scale to pull this venue off – but, for me, this work was deeply problematic. The form felt clumsy and unrefined; it felt like a one-liner that was just dealing on sensationalism and media buzz.

The cost of bringing this work and its maker to Australia might have been better spent on a publishing a catalogue for this biennale, especially given the embedded focus on the archive and legacy in Kataoka’s exhibition.

One wonders whether the tight purse is still a hang over repercussion of the forced withdrawal of Transfield as a primary sponsor, or whether it is more reflective of the overall state of funding cuts in Australia, and the increased volume of activities.

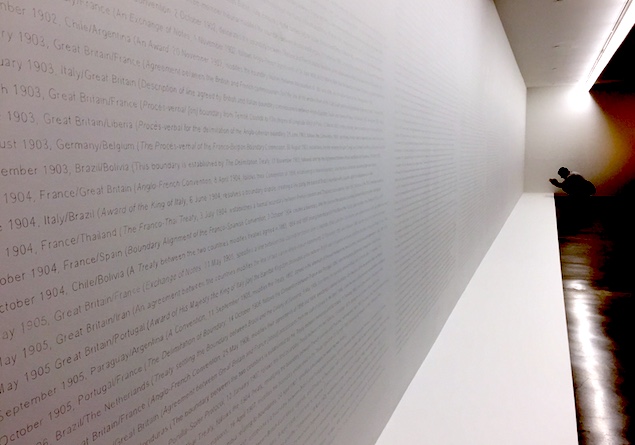

Installation view of the Biennale of Sydney archive at AGNSW; photo ArtsHub

Despite the lack of a catalogue, Kataoka has done a phenomenal job at presenting the 45-year history of the Biennale of Sydney at the AGNSW in a beautifully textured presentation of the exhibition’s archive, that does not come across as too weighty or wordy.

You start to make sense of works such as Tim Nicholson, which documents the instances of creating national boundaries globally as a wall drawing, and pairings across the exhibition such as the historic work by Roy de Maistre with Noguchi Rika, and Sydney Ball’s works from the 1960s with Semiconductor, both at AGNSW.

Tom Nicholson’s Untitled wall drawing (2009-2012) installation view MCA for 21st Biennale of Sydney; Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia; photo Artshub

For me, curating a survey exhibition like a biennale is not about surveying “the now”. That is easy with a little research. But rather lacing, and tracing, context and nuances that extend a conversation through the pairing of works is the greater skill – and it is surprising how few curators do it well.

Mami Kataoka proves to us she is a master at it.

Walking through the individual venues

If you are thinking this exhibition feels smaller in scale than past editions, then you are right. With just 70 artists it is witness to a decreasing trend at play – compared to 83 artists (2016); 92 artists (2014); 101 artists (2012); 167 artists (2010), and 175 artists (2008).

It is most felt at Cockatoo Island. The upper level of the island felt very thin and scattered; the only work of significant impact was Khaled Sabsabi’s multi-channel video installation Bring the Silence (2018), which depicts people of many faiths offering their respects to the great Sufi saints, Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya.

People walk in, remove their shoes, walk over local straw mats, engage with the screen as they float and hover in the space – the experience completed by the smell of rose petals. Su-Mei Tse and Yasmin Smith’s works are also noteworthy.

Koji Ryui Jamals Vu (2018) commissioned by Biennale of Sydney, installation view Cockatoo Island; photo Artshub.

The Turbine Hall did not disappoint with stand out works by Koji Ryui, Abraham Cruzvillegas and Tawatchai Puntusawasdi.

However, it was the two large-scale works, Ai Weiwei’s refugee boat and Yukinori Yanagi’s maze of shipping containers that were the least interesting as artworks.

The AGNSW shone in this Biennale, showing more works than past years and making a conscious effort to embed them within the gallery rather than a temporary exhibition space. The flow from forecourt, down the escalators or from Kaldor spaces, was a more natural conversation.

The only downside to this is that works such as Oliver Beer’s poignant videos Composition for Mouths (2018) within the Indigenous Galleries on the lower level and Francisco Camacho Herrara’s work in the lower Asian galleries could be easily missed.

Installation view of Riet Wijnen’s Conversation six (2018); commissioned by Biennale of Sydney; Roy de Maistre’s work in the background; Photo Artshub.

Stand out works at AGNSW included Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s new video installation Potentiality for Love (2018), Riet Wijnen’s timber construction Conversation six (2018) that weave art histories and alternative biographies, N.S. Harsha’s rethinking of consumerism and human impact in new wall work, and an incredibly moving film by the collective Cercle d’Arts des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC) with hip-hop artist Baloji and Dutch filmmaker Renzo Martens.

Oliver Beer also bring performance and film together beautifully in his video of a long-held male-male / female-female gesture where they breathe into each other in the beat of a song – or Composition for Mouths.

Installation view Oliver Beer, Composition for Mouths (Songs My Mother Taught Me 1), 2018; at AGNSW, commissioned by 21st Biennale of Sydney with assistance from Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac and British Council; photo ArtsHub.

The stand out works at the MCA were by Brook Andrew – despite a little tight in the space; Maria Taniguchi and in complete contrast, the woven sculptures by the Yarrenyty Arltere Artists. March Bauer’s installation of ceramics is also worthy of a nod.

A sure people-pleaser will be Esme Timbery’s wall of shell shoes, and witnessing Ciara Philips at work with her pop-up print studio in the gallery.

Installation view Marc Bauer’s work at MCA for 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo Artshub.

The installation at Artspace was bookended with two incredibly poignant works by Geng Xue and Michael Borremans, however the central gallery that visitors first walk into felt a little congested.

Tiffany Chung and Tanya Goel’s works were also stellar inclusions at Artspace.

Carriageworks – like Cockatoo Island – is always a tough curatorial proposition to ensure the artworks are not swallowed by the impact of the space. Kataoka managed it well, and while only placing eight works there their impact was the stuff of belly punches – that great uplifting reaction when you first walk into a space.

Installation view Chen Shaoxong’s The Views (2016) at Carriageworks, 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo Artshub

Highlights include Chen Shaoxiong’s drum video installation that witnesses the artist’s view from his hospital room as he prepared for his death; Marco Fusinato’s interactive sound work, George Tjungurrayi’s paintings and an incredibly poignant and poetic film by Nguyen Trinh Thi that should not be missed – take the time!

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art is showing just two works – Jun Yang and Akira Takayama that perhaps in concept were a little stronger than their delivery. 4A has however presented them extremely well to tease out their engagement with audiences.

Installation view of Jun Yang’s work at 4A gallery for 21st Biennale of Sydney; photo Artshub

And confusion abounded with Michael Stevenson’s work at Carriageowrks, and equally Haegue Yang’s elaborate installation at MCA which seemed to be trying to take on too much in one space. And Dimitar Solkov photographic series at Cockatoo Island just got lost – conceptually, aesthetically and curatorially.

Overall the dips and troughs were few across Kataoka’s Biennale.

Having recently reviewed the inaugural edition of the NGV Triennial and the current episode of the Adelaide Biennial of Australia Art: Divided Worlds, this 21st Biennale of Sydney proposes an interesting counterpoint. The three exhibitions take a very different tone – NGV Triennial almost shouts at you; Divide Worlds confuses you, while SUPERPOSITION manages to gracefully pull you into a conversation that is curious, respectful, current and strong in its curatorial independence.

Do it in bites, and enjoy the journey that this year’s Biennale offers – it is the best we have seen from the Sydney organisation in a number of years.

Rating 4 ½ stars out of 5

The 21st Biennale of Sydney: Superposition – equilibrium and engagement

Curator Mami Kataoka

16 March – 11 June 2018

Multiple venues. Free

Be sure to take a look at the public programs offered at each venue to get more out of your visit.

Mami Kataoka is the Chief Curator of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.