It was soon apparent that the music would not be the low level minimalism that has filled many a page and many an hour since the 1970s. From the opening ascending string passages it was apparent that the music had much more depth and texture and that conductor, Fabian Russell. and orchestra had risen to the challenge. The chorus then entered with a precision of ensemble and chording rarely heard in Melbourne and reminiscent of the masked chanting of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex as if to say ‘Here is a tale of recent history and possible myth making in our lifetime’. The sets and costumes were more than fit for purpose and the shadow play in the window of the two dimensional airliner showed that the producer understood how to balance realism with abstract symbolism. This was music that could easily be marred by the lack of precision of occasional intrusive vibrato that is readily forgiven in museum opera. The stage was set – could the principals match the standards already set and could the audience be engaged by two and half hours of music written by a living composer?

The answer was a resounding yes! Victorian Opera’s production is one of the most important stagings of musical theatre in Melbourne in recent years.

Barry Ryan’s Nixon had a suitably steely certainty in his public scenes which could be matched when necessary by Bradley Taylor’s aging Mao. Eva Jinhee Kong‘s Madame Mao displayed a rock steady coloratura with a top D capable of pinning any counter revolutionary to the wall in terror. Mao’s three secretaries, all fine soloists in their own right, subjugated their individuality to the greater good of a communalist ensemble with a chording on a par with that of the excellent chorus. Tiffany Speight’s fine lyrical moments of Pat Nixon were perhaps those least flattered by the sound reinforcement which had served well in the earlier declamatory scenes. Andrew Collis’ Kissinger provided a firm bass to the ensembles and he worked hard to portray the cardboard cut-out of an unsympathetic buffoon which the librettist has provided him to work with.

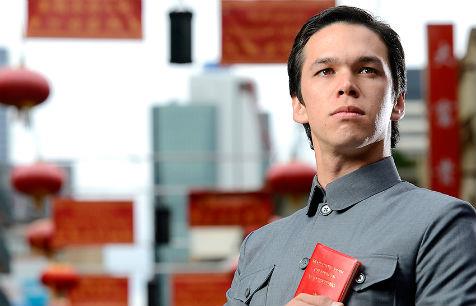

Perhaps the least successful scene was the revolutionary ballet which seemed a little confused as to whether it is abstract and symbolic or good old social realist and equally confused about how to treat the Kissinger-like Chinese character. The social realist segments by the way are impressively lit by Matt Scott who also manages to make the attractive Eva Jinhee Kong look demonic. Still, the segment contains fine dancing. and in such a richly textured work as this, if you have temporary misgivings about one aspect there are plenty more on which to concentrate. Adam’s pastiche ballet score is meant to sound ‘as though it was written by a committee’ but in the end Adams is incapable of writing bad music. Even if you don’t like the music you can admire the sheer professionalism of the conducting and orchestral playing where chording in the high flutes is not to be taken for granted and nor is the tuning of the nominally untuned percussion.

The production offers strong, well-balanced, professional contributions from the time the curtain rises, but this is one opera where the centrepiece comes at the end. Many theatre works send us into the night to quietly ponder and digest what we have witnessed only to be confronted with the obligatory foyer chatter and niceties. The last act of Nixon in China allows us to contemplate what has gone before in a long elegiac scene where the principle characters muse on how they as everyday mortals found themselves behind the public masks in episodes that would blend from news icons to the myth making of our time. Sitting in Her Majesty’s Theatre in Chinatown the audience is given a chance to consider some of the implications for an Australian audience in 2013.

During this act, Adams becomes more rhapsodic and stylistic references to the likes of Ives, Holst and others start to emerge. Perhaps most surprising is the family resemblance to parts of Sondheim –- a composer featured by Victorian Opera later in the season. It is during this act that the quiet dignity and urbanity of Chou En Lai, played by Christopher Tonkin, binds various strands together. This is a delicately nuanced performance and surely it will not be too long before we see this fine performer singing this role on international stages.

With this production, Victorian Opera has set some important benchmarks and thrown down a challenge to their more heavily funded national counterpart to match them in fine ensemble, telling production, and in relevance.

Rating: Four and a half stars

Nixon in China

John Adams

Victorian Opera

Her Majesty’s Theatre

16 May