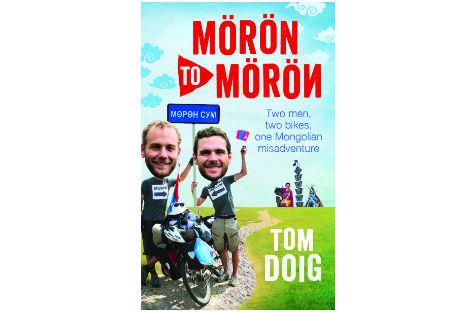

Travel book, adventure memoir, epistolary paean to a friendship, every-man’s guide to cross-country cycling; Tom Doig’s first book, Moron to Moron, could be called all of these things, although as such fails to conclusively be any of them.

The subtitle, Two men, two bikes, one Mongolian misadventure, is the plot, only slightly condensed, and tell-all is the stylistic approach, although in this instance telling ‘all’ doesn’t translate to telling a lot.

Doig’s deliberate anti-intellectualism pervades the narrative, eventually to its detriment. The tone throughout the book is a kind of Kiwi every-man, in essence and vernacular, which makes the book infinitely readable but often lacking in depth – in the rare moments of genuine reflection he grapples with big-picture philosophy and ultimately fumbles; the rules he’s set out for his prose causing it to become clumsy when dealing with anything nearing the abstract. This becomes slightly grating when it becomes clear that the book’s apparent central thrust – the trials and tribulations of two long-time friends mostly alone in a unkempt outpost of civilisation – is going to forever remain effectively untouched. The stated motivation of cycling from one town called Moron – which translates to ‘river’ – to another town called Moron ‘because (they) were there’ is used to excuse Doig from actually providing any insight into the country he’s traversing, in favour of mostly listlessly relaying details of the landscapes and banter he and Tama (the other ‘Moron’) share.

The insight into the practicalities of their undertaking are fascinating but similarly become tedious by their presentation as quotidian, rather than thetical – prompting questions of whether Doig spent enough time considering just what the point of his book was to be. As it is, the book is simply a picaresque narrative whose incredibly simple premise is rendered incomprehensible by the rejection of a recognisable trajectory. There’s no significant treatment of the psychological effects of the journey on the protagonists and the editing, or lack thereof, doesn’t lend any mystery to the pair – their jovial friendship never seems to be tested and efforts to document it as it is are mostly underwhelming for anyone who, like this reviewer, doesn’t share their sense of humour.

Doig’s awkward mixture of irreverence – toward history, high art, their careless lifestyles – and regard – for his best friend, the natural world, Mongols, their physical toil – brings undone his efforts to encourage readers to invest in the Morons’ struggle, intellectually or emotionally. The writing is serviceable but never captivating – Doig often resorts to simply expecting his reader to simply believe him when he tells them a stretch of road is spectacular or emphasise when he tells them his knees are sore. The encounters with various fellow travellers, nomadic Mongols and friendly farmers break up the tedium of the physical narrative but provide little that qualifies as usefully unique experience or contributes anything more than pragmatic development. All of these flaws don’t make the book terrible, so much as falling a long way short of justifying its being one. Though it is readable and certainly would appeal to a particular kind of reader, Moron to Moron really could have been edited significantly and made a feature article or a part of a compendium. Maybe Doig could have held onto the tale until he had enough that he didn’t have to stretch each out into a book. He could have just been brave enough to broaden his perspective on what is possible in his chosen medium – an example which comes to mind is The Bicycle Diaries, by that quintessential anti-elitist art-maker, David Byrne.

2.5/5