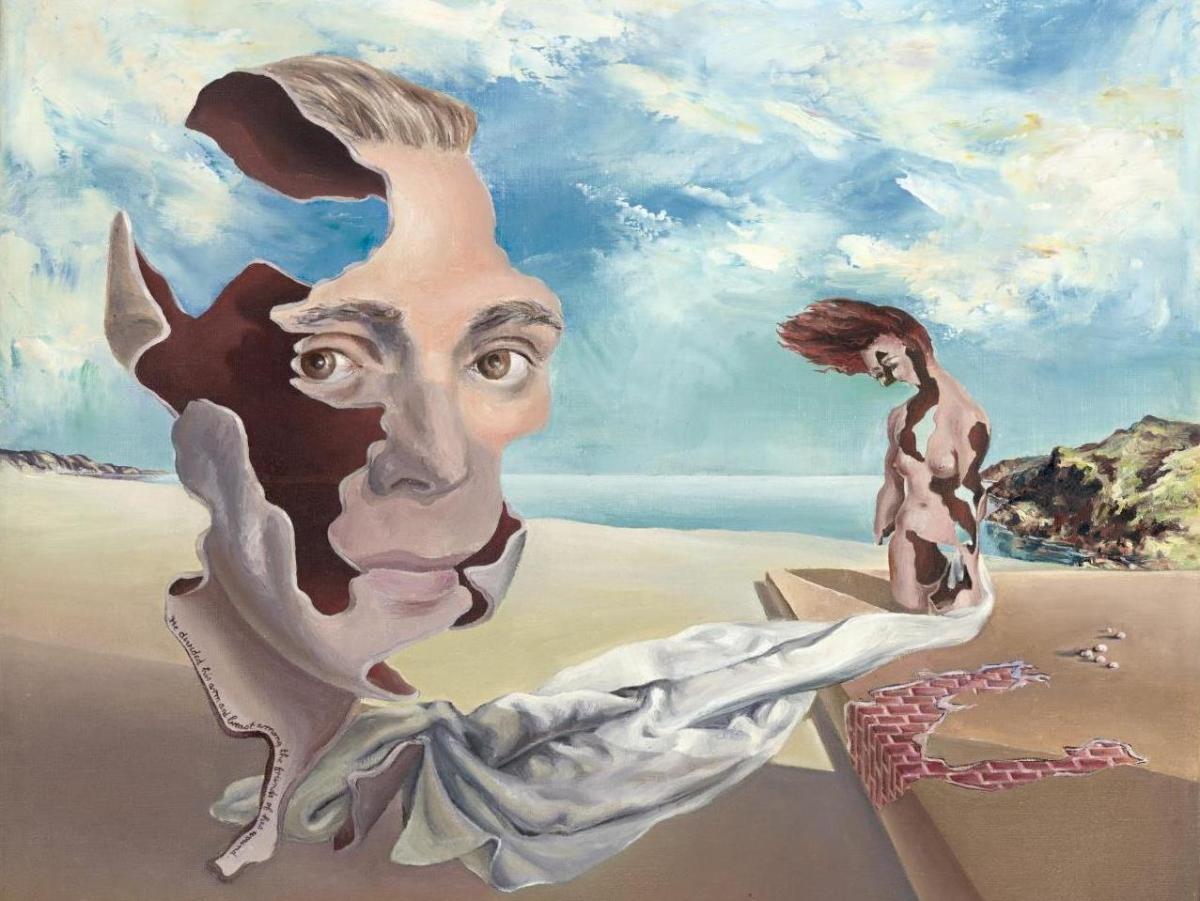

James Gleeson, We inhabit the corrosive littoral of habit (detail) 1940. © Courtesy of the artist

As you enter the sliding doors to Lurid Beauty: Australian Surrealism and its Echoes, currently showing at the Ian Potter Centre, NGV Australia, it is clear that you have entered an alternate universe, confronted simultaneously by Alex Vivian’s unsettling sculptures in which soiled domestic objects emerge from the walls, Barry Humphries’ absurd and whimsical Dadaist accessories, Stuart Ringholt’s upended armchair, and the stomach-turning video of a ring being extracted from beneath hair and a skin-like membrane in Lou Hubbard’s Bore Me.

Lurid Beauty, which takes its name from a 1940 poem by Max Harris, presents more than 250 surrealist and surrealist influenced works by more than 80 artists from major collections across Australia in a variety of mediums. It is the first major examination of Australian Surrealism and its profound impact on Australian art from the 1930s to the present day.

The viewer is asked to leave the rational world, suspend disbelief and journey through the realms of the unconscious and the uncanny. The journey begins, as in Freudian psychoanalysis, with the infancy of Surrealism, with works from the 1930s and 1940s by the movement’s earliest Australian proponents, including Sam Atyeo, James Gleeson, Eric Thake, Max Dupain, JW Power, LeRoy de Maistre, James Cant, Geoffrey Graham and Peter Purves Smith.

Growing out of the Dada of the war years and informed by Freudian and Marxist theory, Surrealism appeared to some as ephemeral, but by the 1930s the movement had spread across the globe. It reached Australian shores through expats working in Paris and New York, and through the lavish, avidly-read art publication Minotaure (1933-1939), founded in Paris and featuring works commissioned by artists including Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, Man Ray and Salvador Dalí.

The movement not only survived but thrived, and impacted radically on the nature of art in the 20th century. Collage, photomontage, assemblage, sculpture and digital technology found a place in everyday Australian public life through their manifestation in graphic design, advertising, fashion photography and commercial illustration.

June 1939 saw the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society (CAS) in Melbourne which included surrealist works by Gleeson, Thake, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester and surrealist influenced works by artists such as Russell Drysdale.

In September of the same year, the Herald Exhibition of French and English Contemporary Art, featuring several European surrealist works, toured Australia’s capital cities. By the 1940s, with Australia involved in a second World War and the aftermath of the Depression years, young artists sought new means to express a growing sense of chaos, alienation and dispossession, and to bring to the surface the horror and absurdity lurking just beneath the civilised social facade.

The NGV exhibition places the pioneering photographic work of Max Dupain and the early experimental collages of Sidney Nolan and Carl Plate alongside photographic images by contemporary artists, such as the hybrid images of Zoë Croggon, the cluttered collages of David Noonan and the dream-like fluid images of Christopher Day.

It also features a number of strong, haunting and disturbing video installations. If…So…Then… (2006), is a mesmerising work by Queensland-born identical twins Gabriella and Silvana Mangano, tracing each other’s outlines with repetitive staccato movements like cloned automatons.

Czech immigrant Dušan Marek’s Cobweb on a parachute (1967), a one-hour “live action” film which was never resolved as intended due to a dispute with his employer, Fontana Films, presents a murky world of shadow and uncertainty, as the protagonist is relentlessly pursued by a creature with unidentifiable features which he eventually comes to accept as the unconscious aspect of his own psyche.

Melbourne video artist James Lynch’s series of short animations explore dream consciousness through a dramatisation of dreams of friends and family about the artist. Viewers are seated on grubby mismatched chairs amid the debris of personal life – a bathroom sink, suitcases, mattress and string of lights and there is a feeling that one has strayed into a private world that may be better left unexplored.

Surrealism speaks loudest in times of uncertainty and chaos, and one of the strengths of the Lurid Beauty exhibition lies in its demonstration of the breadth of the influence of the movement across all genres of contemporary art.

Although women artists were not present in large numbers at the inception of the Surrealist movement, and surrealist works by male artists have often been characterised by violence to and distortion or dismemberment of the female form, female artists today have embraced surrealist forms to express a feminine and feminist perspective, and are well represented in Lurid Beauty.

Particularly powerful is the video by Jill Orr from a 1980 performance, She had long golden hair.

Entering the room to a repetitive male chant of “witch, bitch, mole, dyke”, Orr attached her hair to a series of suspended chains, then invited members of the audience to cut off each section as she recited narratives of women having their hair forcibly cut.

This is reminiscent of the public shaming of women for adultery or who were accused of sleeping with the enemy during wartime.

Julie Rrap, whose extensive body of work spanning more than three decades focuses on the image of the female body in society and the media, responds to the notion of woman as castrated male by casting the negative space between her legs as a solid presence, for the Vital Statistics installation (1997), the photographs depicting a distorted and objectified torso in which Rrap appears almost like a pinned biological specimen.

In Shhh men at work I (2013) Melbourne-based sculptor Claire Lambe uses a splayed foam cushion, a sockette and dainty bronze human feet to suggest female genitalia, sliced through with a sharp polymer resin sheet to depict the fetishisation of the female form.

Lambe draws on her memories of the experimental Manchester (England) music scene in the 1970s to create works in which notions of sexual liberation, exhibitionism, naughty humour and undercurrents of violence collide.

Hobart-based photo media artist Pat Brassington’s ambiguous and uncertain soft biological forms hover unnervingly at the edges of recognition in the photographs from her Gentle series of 2001. The terrible beauty of Louise Hearman’s luminous, yet dark, painted landscapes of pearlescent teeth is the stuff of nightmares and the psychiatrist’s couch.

The exhibition also displays strong work by some of the most notable names in Australian art from the 1930s to the present day, including Clifford Bayliss, Robert Klippel, Tim Schultz, Peter Ellis, Erwin Fabian, and Arthur Boyd.

The exhibition unfolds like a journey through the corridors of the mind, with works clustered by associative themes entering into dialogue with each other – one room a darkened landscape of twisted sculptural forms, another an alarmingly garish orange with green tinged works leaping from the walls.

Although many of the artists featured in the exhibition would not identify as surrealist in their practice, the exhibition successfully highlights the pervasive relevance of surrealist principles of juxtaposition, the dream and the collective unconscious throughout contemporary Australian art.

The journey through the exhibition finishes with a farewell from the taxidermied Maneki-neko, an unlucky black cat wishing you luck as you leave the stage through a black curtain.

A quick trip through the gallery of pioneering works brings the viewer back out to the entry, the final glimpse being of oneself surrounded by the absurd, the uncanny, the disturbing and the uncertain, reflected in the opening doors.

Lurid Beauty: Australian Surrealism and its Echoes is on display at The Ian Potter Centre, NGV Australia until January 31 2016. Details here.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.