Melbourne’s Heide Museum of Modern Art adds further luster to its reputation with the current Kathy Temin retrospective, curated by Jason Smith and Sue Cramer, a thoughtful and revealing synthetic survey spanning 20 years of this acclaimed artist’s oeuvre.

If you are unfamiliar with Temin (or interested from a curatorial perspective to see what constitutes an exceptionally fine show) make time for a trip to Heidelberg. Since her first exhibitions in the 1990’s Kathy Temin has drawn critical attention for the hidden depths and uncannily engaging tenor of her practice. Temin works mainly as a sculptor, in forms that sometimes extend to rope wall drawings, but is as well known for her intriguing felt and fake fur pictures, films, and fused glass panels. More recently she has created large scale monumental fur-clad installations with deeply personal resonances.

At first glance the seemingly roughshod finish and home-made crafty imperfection of many of the pieces- daubed PDF cobbled to create a bird sanctuaries, pieces of loosely cut felt stuck to a board- might distract. And then, on reflection, the works unfold and connect in the mind revealing a humanizing and post-minimalist creative process sustained by her interests in art history, popular culture and explorations of personal identity.

Temin’s work is much influenced Eva Hesse (b1936, d 1970), the late German sculptor, critically lionized in her life time by art historian Lucy Lippard (who curated Hesse in several key shows: Eccentric Abstraction and Abstract Inflationism and Stuffed Expressionism ). Hesse, (like Piero Mazoni’s enabling antecedent in the 1950s) is renowned for reintroducing unorthodox materials, such as plastics and latex into her works that simultaneously re-negotiated the relationship of sculpture to space, the wall and the floor.

Hesse spoke of her works having an internal correctness- not meaning a polished or artisanal finish- but rather of working through the sculpture to find its own latent solutions. This revelation seems a metaphor for Temin’s career. Temin’s fused glass panel Iconic moment: Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse (2004) is on display in the show.

A number of Temin’s Problem Sculptures and Dis-play Sculpture are shown, most famously her duck-rabbit problem, a rendering in white and coloured fur of a diagram used by Ludwig Wittgenstein to illustrate the perceptual “impossibility” of simultaneously recognizing two aspects of an ambiguous figure, in this case a figure containing elements of both duck and rabbit. While the problem Temin worked through here was actually making the sculptures, it is revealing that when experienced first hand (but not in reproduction) the sculpture can read as neither duck or rabbit.

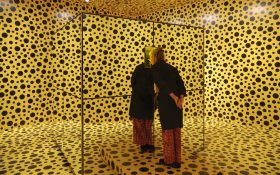

With the possible exception of her fur Bear Sleeping in a Vasarely, (1993) Temin seems not intrinsically interested in problems of perception or of visual psychology. Rather she has been much drawn to the discovery of how easily we connect at a human level- with feelings of tenderness, cuteness, pathos and interest- with her abstract and sometimes almost absurd forms.

Critically, this tendency of the works to evoke or generate our empathy has been related to the “problem” art historian and critic Michael Fried identified in pure minimalist work which is that they have an intrinsic personality, and anthropomorphic latency, that insists on its own presence in the gallery space.

Temin plays with this sometimes overtly in her garden works, such as her “Cactuses (2007)” which have almost dancing gestures and her Family Garden where the tree forms differentiated by size and colour incline towards each other like a nuclear family creating a deliberately anthropomorphized reference. In earlier works the effect can be just as poignant. Her Black and Yellow Corner Problem (1992) shows a stripped form resembling a smashed bee propped up against a corner wall and rendered in fur that is so shabby, and black string that is hung so limply, that the work evokes an irrationally strong sense of pathos. As Robyn MacKenzie noted “Temin wittingly equates the anthropomorphic impulse worrying high modernist aesthetics with the popular anthropomorphism of cartoon culture”. This device makes her work eerily communicative.

Some of Temin’s work is imbued with a wry humor. Interpersonal relationships are not a major theme in her oeuvre but they are put up for a smile: her felted couples have opposing slogans on their T-shirts “I’m a great fuck but a lair” “I’m shit in bed but good at tennis” and “How to terrify a man”. Her installation sculpture My House (2005) had some viewers laughing out loud. This sculpture presents the inner workings of a modernist styled house where we can peer into the rooms. In other habitats Temin has constructed she gave herself the problem of imagining how the space would be used by animals. We can peer through a siding and see a tiny Howard Arkley cat (and important early influence), see the work room where perhaps Temin was struggling on her PhD dissertation on popular culture and fandom around Kylie Minogue, we can see a Kylie obsessed bedroom and listen on head phones to singing auditions in a micro-space that recalls a contemporary gallery white cube. And in another room we can watch actors dressed as koalas in post-coital discussion on their acting work with Kathy for her New York project Pet Corner (Live action) (1991)

The most haunting of her works and perhaps those that are the most masterfully articulate, deal with her Jewish heritage. One of her earliest fur pictures Repenting for my Sins, which was initially displayed during Yom Kippur in 1990 , shows a representation of works by four male artists Vasarely, Malevich, Stella and Mondrian. The Stella source, an X-grid, rendered in green and yellow fur rather than his hand painted black lines (and later rendered as a low bank of crossed walls in the related sculpture Indoor Monument Hard Dis-play (1995) ) is a painting called “Arbeit macht frei” (and Felicity Coleman also cited the very closely related Stella paining “Die Fahne Hoch” in her notes to Temin’s 1995 ACCA show), both of which refer to a nazi swastika.

While Stella claimed that the subject of this series of work- the Black paintings- was just the painting, the titles and also notes he made in drawings for the series which refer to the Final Solution, identify their relationship to the Holocaust. Temin personalizes this in her Indoor monument: a monument to the home (in the Rumpus Room) where a letter she found after her father, a survivor of Sachsenhausen concentration camp, had died, is looped on a small TV screen. He writes a family narrative and seeks other surviving Temin relatives across the world. Temim’s father was also a tailor forcing reappraisal of her use of sewn materials.

Temin uses the Stella grid as the floor plan element for her My monument. White forest (2008) which is a response to her visit to memorial gardens in Europe and Japan. Superficially inviting the vast tree forms, anthropomorphized and crowded, have a ghost like quality . The soft white weightlessness, and the Wedgwood blue sky, seems to evoke bleak and barren snowed in stands of trees in the depth of winter. There are no scenic allees or vistas. The forest is constraining and sad. Unoccupied benches evoke absence. Temin created this work for “Australian Optimism” and has said she finds it hopeful. Not so its counterpoint pendant currently on show at Anna Schwartz Gallery My Monument; Black Cube (2009) here the plush black trees are crowded, squashed together oppressively almost cowering in the cavernous gallery hall. Temin, in the catalogue interview with Andrew Renton, has discussed Black Cube in the context of her interest in mourning jewelry.

I found it hard to full appreciate or approach these works, because I do not share Temin’s heritage. I thought of the enduring anguish I have experience through friends and their families who include survivors and descendants of the murdered. It also helped to think back to the long and anguishing discussion that followed Louise Adler’s floor talk on Berlin during the recent Tacita Dean show at ACCA. There members of Melbourne’s Jewish community at one point shared, without consensus, views on memorials that were meaningful to themselves and their own families.

Temin seems not to be trying to create grand or universal statements, but by creating monuments that are entirely personal she provides an accessible point of contact for a broader audience not personally touched by these horrors. The evocative potential of her humanized and humanizing sculpture creates wordless memorials of enduring and deeply moving eloquence.

Kathy Temin

1 August – 8 November 2009

Venue: Heide III: Central Galleries

Curator: Jason Smith & Sue Cramer