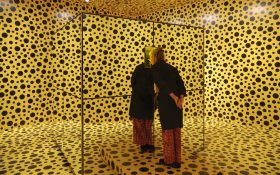

Installation view Reverse Cinema (2015), an installation by New Zealand artist Judy Millar. Photo Mark Pokorny. Courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf.

Judy Millar represented New Zealand in the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). The timing of her Sydney exhibition with Sullivan + Strumpf in this current Venice season, then, points to a punctuation in a career and the kind of conversations that we construct, and then attempt to work against, when that aesthetic signature becomes so defining it can be constraining, airless. How one moves forward or backwards, sideways or left-field can be challenging.

Millar pulls it off superbly in some respects in this exhibition, the smaller gestures within the show more captivating against the bold stokes and movements; tensions created and illusions cast. She is a magician of material play that never strays too far from her conceptual foundations.

However, this exhibition is not a new idea for Millar, despite it being the first installation-based site-responsive exhibition that Sullivan+Strumpf has presented.

Its precursor was a much larger scaled installation at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (IMA) in 2013, Be Do Be Do Be Do, where Millar had the luxury of space to push the gesture within the same black and white register, allowing it to leap and flow. The exhibition had a great sense of flight, whereas those movements felt congested at Sullivan+Strumpf, causing the show to get slightly bogged in eddies of folly.

Judy Millar is an artist who likes to take painting off the wall. To be exact, she described the show as, ‘a painting that had exploded in space’. This exhibition fleshes out that thesis perfectly. We are witness to her deconstruction of painting and then its reconstruction, pushing and pulling between semantic understanding of the medium and a more visceral gut engagement. This is where the show sings.

Starting with a black and white painting that Millar converts into a half-tone dot process – the traditional building blocks of print media – she takes that pixelation and blows it up to steroid-sized proportions. It then flits between actual paint on canvas, to digital prints of the painted surface presented standing like placards on foamcore frames, projected gestures and sculptural archi-forms that extend painting to the 3-dimemnsional realm. She embraces a mantra of no hierarchy across mediums.

It is a self-referential system that she assigns; its repetition a reflection on contemporary painting and a more analogue experience of materiality. It has become signature for Millar.

She blurs the lines between painting and printing processes, then dives into that crossover zone with sculpture, where the physical mark on the canvas is extracted and reconsidered as a gesture within an architectural conversation. No one can argue that this exhibition isn’t physically and mentally playful, but does it go to far?

An example was a work that takes its cue from a pop-up book Millar produced, articulated as a folded sculpture on a pulley system that required the viewer to activate it. It is an obvious thing for Millar, to want to push that narrative into a 3-dimensional gesture in the gallery space – into the real world – where we become more physically engaged in painting. However, the compressed gallery setting creates a physical and mental obstacle course. It is slightly too active; too congested.

This exhibition is most successful when it turns to an architectural conversation rather than a gimmick. Paintings that are seemingly plucked up and hang suspended, anchored by ropes; a painting that sits on a ply armature that is rolled and ribbon-like, echoing the very gesture of the brushmark, again held aloft this time by a pair of ladders. A small group of canvases, more formally hung at the rear of the exhibition, sit portrait-like as a kind of dictionary reference to Millar’s personal vocabulary. They are a great anchor.

Shadows meld with projection marks; the viewer becomes an active agent in this cast landscape. Where are the edges of illusion and physicality? We are seemingly caught in this mark. Reverse Cinema is a constructed world in every sense.

Overall the exhibition has an Alice in Wonderland Lewis Carroll quality (I am sure a feeling expressed by others before now) for its mere fanciful flight and journey that it leads audiences on. Millar said that it is the role of the artist to push imagination; to delve into the absurd, the ridiculous.

While the first-line response encountering the show is one of play, there is a much more challenging layer that brews and punches below that surface the longer you consider the work. In her exhibition text Rosemary Hawker described Millar’s work like a racing car slamming into a safety barrier, motion arrested. There is indeed a frontier quality about Reverse Cinema; a brave rethinking of painting that is particularly attractive to a honed eye, throwing you off course. It’s a good feeling and the slam is a welcomed jolt.

Conceptually and viscerally this is a great show. My only criticism is that it is too confined in this particular space. Sure, Millar is playing with that viewer experience and teasing them through a kind of navigation, but is the game lost to the lack of play room?

Regardless, it is worth catching this exhibition before it closes. It opens a window and lets a fresh breeze rush in. Take that white cube!

Rating 3.5 out of 5

Judy Millar: Reverse Cinema

23 May – 13 June 15

Sullivan + Stumpf

Elizabeth Street, Zetland (Sydney)

www.sullivanstrumpf.com