Watson was deeply influenced by the Melbourne punk scene of the 1970s, which fused with her art making and her signature style of embedding text.

In 1993, Jenny Watson represented Australia at the Venice Biennale. She was only the second female artist to be selected for Australia, and the third artist to be presented in the then-new pavilion designed by architect Philip Cox. Watson was at the top her game, and her name was on everyone’s lips. But she felt the moment was a little premature.

Writer and academic Sasha Grishin reports Watson telling him on ‘a number of occasions that it would have been better if this had occurred a bit later in her life’. Perhaps that moment is finally right.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s Curator, Anna Davis, has curated a phenomenal survey exhibition covering 45 years of Watson’s career.

The announcement of the Watson survey perked my interest (as I am sure it did others). What had Jenny Watson been up to since the hype of that Venice pedestal in 1993, and why had the spotlight diminished to a mere flicker over the past 24 years?

Had the “bad girl” of Australian art simply slipped out of fashion?

We all know this art world we choose to locate our careers in is fickle. Watson, however, seems to have been unruffled by the boom and bust roller coaster of stardom – from Venice fame and an international career in sync with the rise of feminism and punk culture in the 1970s and ‘80s, a high flying art market of the 1980s and ‘90s that was eventually deflated by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and shifting tastes back home. She just kept going back into the studio.

As MCA Curator Anna Davis said: ‘Jenny Watson has remained true to her ideas over time and continues to vigorously pursue her conceptual painting practice in an impressive career that stretches over more than four decades.’

The work remained consistently bold, individual and “top drawer” in its contemporary dialogue, and the MCA’s exhibition The fabric of fantasy is an affirmation of an artist who has been unwavering in her focus and practice. This is exactly what survey exhibitions are about.

Installation view, Jenny Watson survey at the MCA; photo ArtsHub

Fresh lens on an old favourite

Walking into the gallery space one immediately taps into a kind of energy that pulses through this exhibition, somewhat to the beat of punk music and partially caught in the eddies of saccharine nostalgia.

Watson’s works have an everyday feel – familiar scenes with horses and frocks, ribbons and pretty detail, populated by Watson’s own image and her alter egos – sliding between fiction and autobiography.Fabric and text are key; phrases snipped en route and textiles collected on journeys that are edited and added for maximum eloquence and effect. Earlier in her career, language fragments were often added into a composition, while more recently, text is presented as a separate panel alongside a larger image, creating an informal diptych.

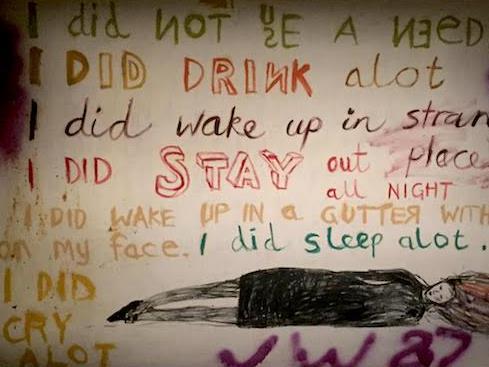

Detail from Watson’s series from the 1980s where she first began to separate out text – according to Watson these text components represent ‘the subtext of existence’ – the words in our head that we have been trained not to think about while we are looking at art.

The exhibition is peppered with Watson’s signature use of horsehair tails, buttons and sequins – it has a quirky “girly” quality to it and, yet, these works are also boldly narrative in a dark suburban way.

Davis explains: ‘Questions about what it means to paint and “what constitutes a painting” fuel [Watson’s] practice, as does an examination of how our everyday thoughts influence how we look at art.’

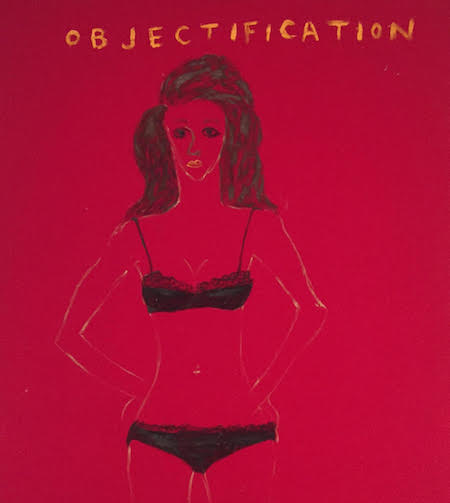

She continued: ‘Watson became motivated by her encounters with feminism and punk in the 1970’s, turning to her immediate and inner life for inspiration and beginning to develop the spontaneous style of painting she continues to work in today.

‘This was a time when much of the art world was dominated by male artists. The feminist art movement reinforced her ideas that female experiences were a legitimate artistic subject matter.’

With so much already going on in the works themselves – both graphically and conceptually – a clean “white cube” style hang would have been the most obvious choice. However, Davis has pushed the presentation of this exhibition so that – as a whole – it works as one of Watson’s works would, pulling the viewer into the narrative.

Installation view, The Jewel Box, Jenny Watson survey at the MCA; photo ArtsHub

The journey starts with the earliest works on a backdrop of baby blue and crème stripe walls, finishing up with Watson’s most recent paintings cast against pale pink walls with a white diamond cut. She has called the room The Jewel Box, describing the collected elements as ‘colourful talismans’, each one recalling specific memories, dreams, feelings.

I am always a little wary of painted walls – a kind of bonus interior décor to compliment the artworks – but in this case it extends Watson’s works beautifully, and if anything adds to the seamless consistency of this exhibition.

I also want to make mention of the wall labels – love them. Simply addressed in relation to the viewer’s physical position, “At Left … Behind … From left to right”, they free up the space so that the works sit in conversation with the walls and as a collection in the room.

Installation view, Jenny Watson survey at the MCA; photo ArtsHub

Feminism and Punk are classics

Close to the entrance to the exhibition is a side gallery that has been set up as a kind of ‘Hall of Fame’ for Watson’s pop idols from The Beatles to 1970’s Punk Rock – the tone changes.

The large text/figurative works in this room are full of energy and reverent irreverence; our viewing is backed by a soundtrack complied by Greg Ades to help us get in character.

Taking in The Mad Room (1987) one reads across paintings: ‘I Did Drink A lot / I Did Wake Up in Strange Places / I Did Wake up in The Gutter with Blood on my Face / Woman Dying Her Hair on a Wet Afternoon / I Did Not Use a Needle’ (pictured top)

Davis explains: ‘Living in St Kilda in the late 1970s, she witnessed the emergence of Melbourne’s punk scene at venues such as the Crystal Ballroom and the Tiger Lounge, and became part of the inner-city pub culture’s mix of music, art and fashion.’

Much has been made over the years of a parallel place that Watson occupies with artists such as Tracey Emin and Jenny Holzer (due to her use of text). As Grishin recently asked: ‘Is Jenny Watson Australia’s equivalent to Tracey Emin? Watson is about a decade older; she is less concerned with listing everyone that she has ever slept with and more obsessed with horses, but shares Emin’s interest in punk and street culture, feminism, the conceptual dimension of art and the use of unconventional materials.’

I think the question – and the answer – is largely irrelevant.

Casting an eye across this exhibition of more than a hundred works the resounding conversation that Watson has with the viewer is incredibly individual. There is no doubt or redirection in her focus. I have been delightfully surprised how cohesive this survey is, and how strong its impact still resonates, and yes… how fresh the work still looks.

Judy Annear’s selection of Watson for the Venice Biennale may well have been premature, but it was incredibly insightful. Watson is an artist who has made an indelible mark on Australian art history – and continues to.

Rating 5 out of 5

Jenny Watson: The fabric of fantasy

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Circular Quay, Sydney

5 July – 2 October