Wilam Biik (Home Country) is a multi-layered conversation between Country, people and ancestors that surges with the power of Aboriginal connectivity.

The first major exhibition curated by Wurundjeri and Dja Dja Wurrung woman Stacie Piper in her role as Tarawarra’s 2019 Yalingwa Curator, it is a generous offer to see Wurundjeri biik (Country) the way Wurundjeri see it — not as a ‘natural resource’ to be exploited, but a life-sustaining force interconnected with all things.

It is an important call to those who live on Wurundjeri biik to uphold Wurundjeri people’s principles of relationality: to live in reciprocity with all life, including land, animals, water, sky and people.

The exhibition embodies the Wurundjeri concept of layers of biik: country extends from below the ground to above in the sky, all interconnected through water country.

Read: How Aboriginal perspectives are transforming archaeological histories

Piper gathered artists by following the ‘waterlines’ and ‘bushlines’ which connect Wurundjeri to the 38 Aboriginal groups throughout south east Australia.

These artists offer a different way to look at Country. Not by the roads we travel, but by the relationships embedded in it.

CARE FOR COUNTRY

Piper developed her curatorial practice at Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre after working for many years with her Elders at Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation.

The vision for Wilam Biik came from Piper’s sovereign responsibility to care for Country, and her despair at the unsustainable logging of old growth forest in the Warburton ranges not far from Tarrawarra on Wurundjeri biik.

Climate trauma and relationship to country was the starting point for Stacie’s curatorial vision. Wilam biik embodies the rich knowledge of Country that holds the answers to recovering from this trauma.

The exhibition is grounded in land and ancestors. Audiences are welcomed by a wall-sized historical photograph of Wurundjeri biik and baluk (people) at Corranderrk.

‘Ancestor tools’, such as Barak’s carved parrying shield, a boomerang and basket – on loan from Melbourne Museum – are displayed in the way they would be held: close to the people.

Eel trap by Wurundjeri Elder Kim Wandin underlines the continuing connection between generations.

In conversation with the sepia image of their ancestors, their living descendants – the Djirri Djirri dancers – are projected dancing on Wurundjeri country in the upper reaches of the Birrarung.

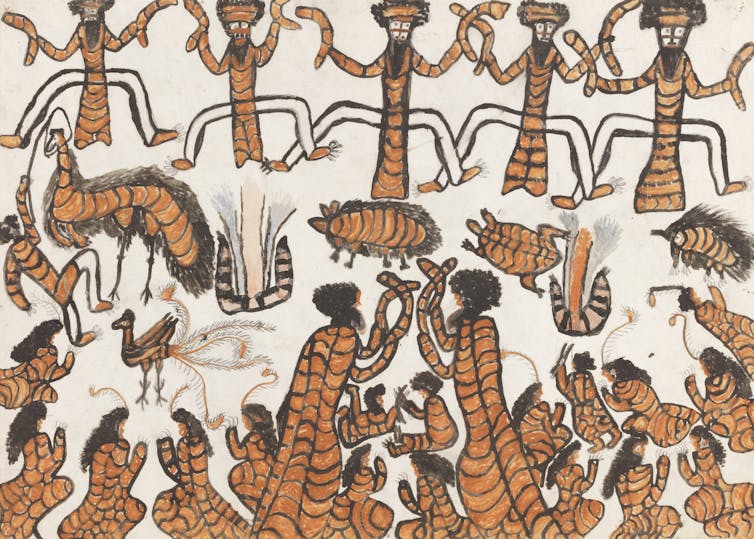

Ceremony (c1895) by Wurundjeri painter Ngurungaeta Wiliam Barak has been brought to wilam biik by Wurundjeri people for the first time since they were made. The painting details ceremonial adornment, as referenced by the Djirri Djirris today.

WATER, LAND, SKY

Following the water sources that start in Country shared with Gunnai and Taungurung Peoples, Gunnai and Gunditjmara artist Arika Waulu’s matriarchal Digging Sticks are carved wood adorned in gold, set against a wallpaper showing layers of country and the cycle of plant life. In this, Waulu speaks of women’s interconnectivity with Country.

Of the Earth, an installation by Taungurung artist Steven Rhall, places a photograph of a boulder on a sound platform, animating the image in a contemplation of the deep time written into Taungurung Country, or in what Alexis Wright has called the ancient library.

The water connection flows through Dhunghula (Murray River) to Yorta Yorta, Waddi Waddi, Wemba Wemba, and all the way to Ngarrindjeri Country as well as into Kolety (Edwards River) and the Baaka (Darling River).

Read: Australian undercurrents: Why curators are (still) fixated on water

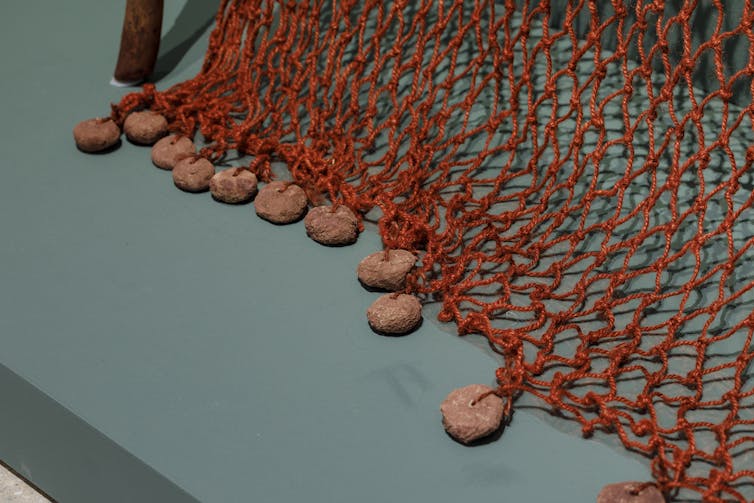

In Drag Net, a woven net incorporating river mussel shell, Waddi Waddi, Yorta Yorta and Ngarrindjeri artist Glenda Nicholls evokes this connection to the river and “water country”.

In Wemba Wemba and Gunditjmara artist Paola Balla’s intergenerational work, Murrup Weaving in Rosie Kuka Lar with Rosie Tang, Balla builds a camp house made from cloth imbued with bush dyes in the landscape of her grandmother’s painting of country. Through these bush dyes, Balla brings the smell of “on ground country” directly into the gallery.

Barkindji artist Kent Morris’ Barkindji Blue Sky – Ancestral Connections is a stunning photographic series, embodying water connections to the Baaka as well as ‘sky country’.

MANY VARIED RELATIONSHIPS

Waterlines like the Birrarung and the Werribee River, marking connections and boundaries with the Boonwurrrung, Wathaurong and Tyereelore, are mapped with kelp baskets by Nannette Shaw and paintings by Deanne Gilson.

These artists reference the transition from freshwater to saltwater and the relationships that exist amongst the Kulin, across to Tasmania and all life forms within Country.

Wilam Biik speaks of the powerful connections between artists, Peoples and Country. It is also a testament to the power of Aboriginal knowledge in Aboriginal hands, and the centring of south east artists and curators as the experts of their knowledges, practices and Country.

Importantly, it is also a call to learn how to live in good relationship with Wurundjeri biik and baluk.

![]()

Wilam Biik (Home Country) is showing at TarraWarra Museum VIC until 21 November.

Kim Kruger, Aboriginal Lecturer and Researcher, Moondani Balluk Academic Centre, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.