This exhibition has been brought together by two female curators who are also academics, Lisa Radford and Yhonnie Scarce. Lisa Radford is a Lecturer in Art, Painting, at VCA in Melbourne, and an artist and writer. Yhonnie Scarce belongs to the Kokatha and Nukunu peoples. Scarce is an interdisciplinary practitioner whose work often references the on-going effects of colonisation; in particular removal and relocation of Aboriginal people from their homelands and the forcible removal of Aboriginal children from family.

‘Both women travelled to various sites around the world investigating the commemoration, or deliberate sequestration, of acts of genocide, colonisation and nuclear trauma in the curation of this remarkable, contemplative exhibition.’

From the catalogue, in the words of Dr David Sequeira, Director for the Margaret Lawrence Gallery (where the exhibition will travel to next) ‘The exhibition is the result of complex field trips, interviews and web/text-based research. Discussions, including rich conversations with the curators’ extensive network of family, friends, artists, writers and academics… a suite of observations which have been developed and now flourish in this exhibition.’

Both women travelled to various sites around the world investigating the commemoration, or deliberate sequestration, of acts of genocide, colonisation and nuclear trauma in the curation of this remarkable, contemplative exhibition. It is a cerebral offering, densely surrounded by academic texts compiled by contributors, and essayists, referencing the work. At the heart of the experience, though, is the art.

Read: Exhibition Review: Mervyn Bishop, National Sound and Film Archive (ACT)

The art sits, in its delegated positions within the sombre walls of ACE Open, a modest gallery tucked inside The Lion Arts Precinct; a collection of dated, red brick buildings adjacent to the University of South Australia’s City West Campus, on the edge of Adelaide’s CBD.

At first look, it is an unassuming collection, notably there are no artist statements on display next to each work and in the larger of the two gallery spaces, there is nowhere to sit, even though some, if not all, of the works are beautifully presented, so as to invite reflection and contemplative minutes. It is an uncomfortable space and perhaps deliberately so.

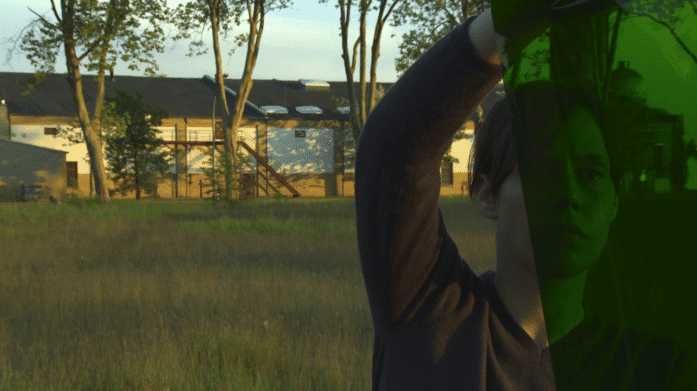

Mareike Bernien and Kerstin Schroedinger, Rainbow’s Gravity (2014), HD video, 33 minutes. Courtesy the artists.

As an example, Unbound Collective’s Sovereign Acts │ In the Wake draws you in with its warm, glowing, organic materials, and as you peer closer at suspended, dome-shaped, internally lit, banana-paper structures, it only then becomes clear that these are carefully chosen, printed collages of jaw-droppingly horrific archival documents, referencing an abhorrent white dialogue around Australian ‘natives’ dating back to the 1940s.

This exhibition is a rare treat for Adelaide audiences, a complex, contemplative exhibition with much to say and much to engage with, a small portion of which is detailed here.

In 1950, the then Australian prime minister Robert Menzies agreed to nuclear tests across three sites in Australia, Monte Bello Islands off the coast of WA, Emu Fields and Maralinga in South Australia. The damage to Aboriginal people includes forced displacement, injury and death and to this day, the extent remains unquantified. Sculptural, photographic, and painted artworks in response to the blasts feature prominently in Concrete Archives.

Sanja Pahoki, A Postcard from Jasenovac (2021), duratran, lightbox, 43 x 29cm. Courtesy the artist.

Pam Diment’s poignant glazed, clay mushrooming Maralinga and Warren Paul’s earthenware works Marcoo, devoid of artist statements (and title) in location, invite the viewer into the unsettling realm of ‘this is disarmingly beautiful, oh-my-goodness-what-am-I-admiring?’ moments, the sort of realisation that contextualise much of the offerings in Concrete Archives.

It is good, it feels right and just; to experience the slow blossoming, internal weight of awfulness, revulsion and sadness derived from admiring the works. A testament to the quiet power of Concrete Archives.

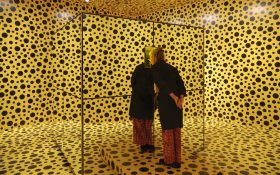

Part of Korpys/Loffler’s 22-minute work (shot handy-cam style on super 8 film), Reflecting on Absence asks the viewer to consider tourists who have been captured encountering the 9/11 memorial’s. These reflecting pools take up nearly an acre each on the site of the Twin Towers in New York City, fearsome water sculptures, referencing a void, and they are the largest man-made waterfalls in North America. During it, The Image is Not Nothing (Concrete Archives) really leaps to life. Scraping, dripping, muffled, watery movements and intermittent vocal consonants amplify and intensify the deeply sombre mood in the gallery as layered audio fills up the rooms. Perhaps, it is for this reason, the curators have chosen staggered screen times for the five digital works, the longest of which is 33 minutes and the shortest is just under 6 minutes.

This feature means a truly immersive experience is a minimum time commitment of one and a half hours, or alternatively, multiple return trips at specific, predetermined times to catch all the digital works. This is a big ask given the heavy subject matter, but it stands to reason that each of the large-scale digital works does not compete with one another.

Rosemary Laing, one dozen considerations, Totem 1, Emu (2013), C Type photograph, 26 x 54.3cm (image size). Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne.

Within Concrete Archives is an atmosphere of reverence. The viewer is being asked to stand witness, observe and engage with a wide variety of responses from a magnitude of horrors; and there lives a tangible, horrible beauty here.

Megan Cope’s Morning for Menindee (dry clay, emu eggs with decal, feathers and fish scales) lies unprotected on the gallery floor. This approximately 1.1 metre wide, assembled sculptural work reads like a ‘look what we’ve lost’ moment; delicate and delicious, a nod to vitality no longer present. We are made acutely aware of loss, the artist having captured an essential vulnerability in her arrangement of cushioned, emu eggs. It comes with a painful lack of context. Attendees can appreciate the beauty and the time dedicated to the composition, although it feels a bit like standing on the outside grasping at straws.

‘Viewers become the recipients of hard truths, given the unenviable opportunity to hold a mirror to the complexities of our nation’s past, present and possible futures.’

The dense catalogue serves to provide an overarching framework and, in relation to Cope’s Morning for Menindee a quick Google search after leaving the gallery uncovers the title Menindee is drawn from a NSW town. It is the place where Burke and Wills stopped on their journey to the Gulf, and more recently the site of mass fish deaths during the unusually dry summer months of 2018/19. Water resources overallocation in the region and drought resulted in 1 million fish deaths.

The Image is Not Nothing (Concrete Archives) feels like a tightly packed suitcase of tragedies and remembrances, revealed (or concealed) in such a way that one may unravel infinite stories and experiences, stopping to marvel at one’s own ignorance. Viewers become the recipients of hard truths, given the unenviable opportunity to hold a mirror to the complexities of our nation’s past, present and possible futures.

It tears at the soul and raises valuable questions. If you are in Adelaide go and see this is unmissable content at ACE Open. Spend some time opening your mind.

Rating: 4 ½ stars out of 5 ★★★★☆

The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives)

Premieres at ACE Open as part of the 2021 Adelaide Program before touring to Margaret Lawrence Gallery, The University of Melbourne

Curated by Lisa Radford and Yhonnie Scarce

26 February-24 April 2021

FREE