At each of the multiple venues presenting the 24th Biennale of Sydney, visitors are greeted by a brightly coloured painting of an ATM: the works of Manyjilyjarra woman Doreen Chapman (Jigalong, WA), a non-verbal, deaf artist known for her uninhibited painting style.

These ubiquitous machines represent a point of transaction – a transfer of currency – and, when placed within an artistic vernacular, one can’t help feel that Artistic Directors Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero are asking the question, “at what cost does culture come to us?” and reminding us of the value of creative exchange.

It is a wry and sensitive entry point, given that it is easy to feel jaded by these big, spectacular exhibitions, which take on so much and yet often fall back on familiar names doing the global “biennale circuit” – a kind of “art world currency”, to pick up on Chapman’s ATMs.

In contrast, this 24th edition of the Biennale feels exuberant and fresh. And, for many Australians, it offers an introduction to art from regions less featured and presents parallel histories for consideration. We come away feeling we have been welcomed into a new creative circle and buoyant with new learning.

The duo’s theme, Ten Thousand Suns, is rooted in the idea that something as all-knowing as our understanding of the sun also has a plethora of layered meanings, offering countless perspectives on our world. Costinaș and Guerrero say their exhibition proposes ‘radiant forms of resistance that affirm collective possibilities around a future that is not only possible, but necessary’.

In a nutshell, we are witness to familiar and shared histories, colonialisms, joys and apocalyptic futures, but expressed in a “thousand” different ways by these 96 Biennale artists.

A quick example playing out at the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) is a room of works that explore World War II. A traditionally styled tais cloth by Timorese artist Magdalena Meak shows Japanese planes heading towards Australia, while Tiwi artist Pauletta Kerinauia paints those same planes from their own perspective – both touching on how oral histories continue culture.

Connecting venues/connecting nations

Doreen Chapman is not alone in forming cross-venue connections in Costinaș and Guerrero’s Biennale. A number of artists are thoughtfully placed to offer a through-line – anchors if you like – that stitch together ideas and give a sense of flow and familiarity for viewers. It is not a new concept, but Costinaș and Guerrero pull it off superbly.

Obvious examples are Eric-Paul Riege’s (Diné/Navajo, US) sculptural installations, which are made from wool and which stack and define space at both White Bay Power Station and Artspace while speaking to traditional weaving practices and trade.

Another is tattoo artist Mangala Bai Maravi (India) who replicates traditional body markings in large scale on canvas to ensure their survival, at both White Bay and Chau Chak Wing Museum (CCWM) at the University of Sydney – two venues making their Biennale debut this year. The long-standing practice has ties to Hindu mythology and has come under threat in recent years due to the displacement of the Baiga people.

Another great example is the work of William Yang (Australia), whose ideas anchor various narratives from indentured labour to queer activism, across the UNSW Galleries and CCWM. Where this weaving gets interesting is in an enormous portrait of dancer and activist Malcolm Cole, which towers over the entrance vortex at White Bay and takes its trigger from a photograph taken by Yang of Cole dressed as Captain Cook at the 1988 Mardi Gras.

It has been ambitiously painted by Yuwi, Torres Strait and South Sea Islander man Dylan Mooney, who is legally blind and uses technology to produce high-impact works, here blending rainbow queer culture with the Rainbow Serpent.

While connections are key across this Biennale, each of the six venues can stand solidly on its own, allowing staggered viewing over the exhibition’s duration.

When ArtsHub spoke with Costinaș and Guerrero back in July last year, they explained: ‘The venues will be quite different – I think acknowledging the radically different types of institutions and the function that the different venues have, the histories that they have, the different architecture and spatial experiences that they offer – that should be mirrored in the curatorial set-up,’ Costinaș said.

They have delivered on that vision, and it is easily felt by visitors.

Also defining this exhibition is its brightly coloured walls, which play out those nuances and add a sense of fiesta, pushing audiences out of the “white-box experience”.

Speaking generally, the exhibition also has a rich materiality – happy to insert traditional crafted objects by “unrecorded makers” alongside contemporary artworks, celebrating traditional crafts anew and with a rigour that is on point for today’s conversations.

Engaging, thought-provoking examples are the neon wall-based sculpture of Bard man Darrell Sibosado (Marapikurrinya/Port Hedland, WA), which uses the traditional patterns of riji riffing off the luminescence of the pearl shell at White Bay, and in a neighbouring space Peruvian textile artist Cristina Flores Pescorán, who weaves gauzes inspired by Incan healing practices to speak of her own body, health and feminism.

This continues with the incredible beaded works of Nádia Taquary (Brazil), which are among the first works seen at AGNSW, and the beaded “paintings” of Big Chief Demond Melancon (US), which draw connections between Zulu warriors and First Nations traditions, blending spirituality, craftsmanship and queer pride.

Another characteristic that defines this Biennale is a strong Pacific narrative across materiality and cosmologies. Costinaș and Guerrero have made a point to foreground First Nations narratives, but it is down with a spirit of celebration rather than the pummel of activism.

This is no better illustrated than through a new commission by Yankunytjatjara artist Kaylene Whiskey, with her White Bay installation Kaylene TV, where audiences can step into a giant TV with human-size cut-outs of icons such as singers Cher and Dolly Parton.

‘At a time when all screens seem to be overflowing with stories of crisis, corruption and chaos, Whiskey makes space for a playfulness and spirit that disavows narratives of inevitable demise,’ explains the Biennale.

Whiskey is among nine of the 19 commissioned works at White Bay that have been delivered through a partnership with Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, which has also supported projected works by Nikau Hindin and Gail Mabo on the sails of the Sydney Opera House – a late addition venue, but a fitting one circling back to the inaugural Biennale of 1972.

Some highlight artworks not to be missed

For its debut, White Bay has pulled it off – not only in delivering this exhibition, but also in teasing out its future. In addition, it will be a hub for performance across the exhibition dates. Costinaș and Guerrero have a really good spatial read as curators, drawing our eye up and through the venue, punching across levels, but also using smaller side rooms for more intimate works and videos, and then the grand statement of the Turbine Hall.

Among the highlights here are three carnivalesque kites by the all-female group Orquídeas Barrileteras (Guatemala) each spanning five metres wide, brightly coloured and made from natural materials. They stare down upon you with an escapism and a narrative of resilience that is life affirming. These works have been painted by deaf artists.

In complete contrast, Costinaș and Guerrero take on the challenge of the low ceilings of UNSW Galleries and yet still create an exhibition with a feeling of scale and bold impact.

Walking into the lower galleries visitors will find three incredible organic sculptures and a video by Yangamini (Tiwi, Gulumirrgin, Warlpiri, Kunwinjku, Yolŋu, Wardaman, Karajarri, Gurindji, Burarra, Australia) – a group of artists formed around the energy and spirit of the Tiwi non-binary community. The works play off the devastation of gas refineries and gas as a bodily function.

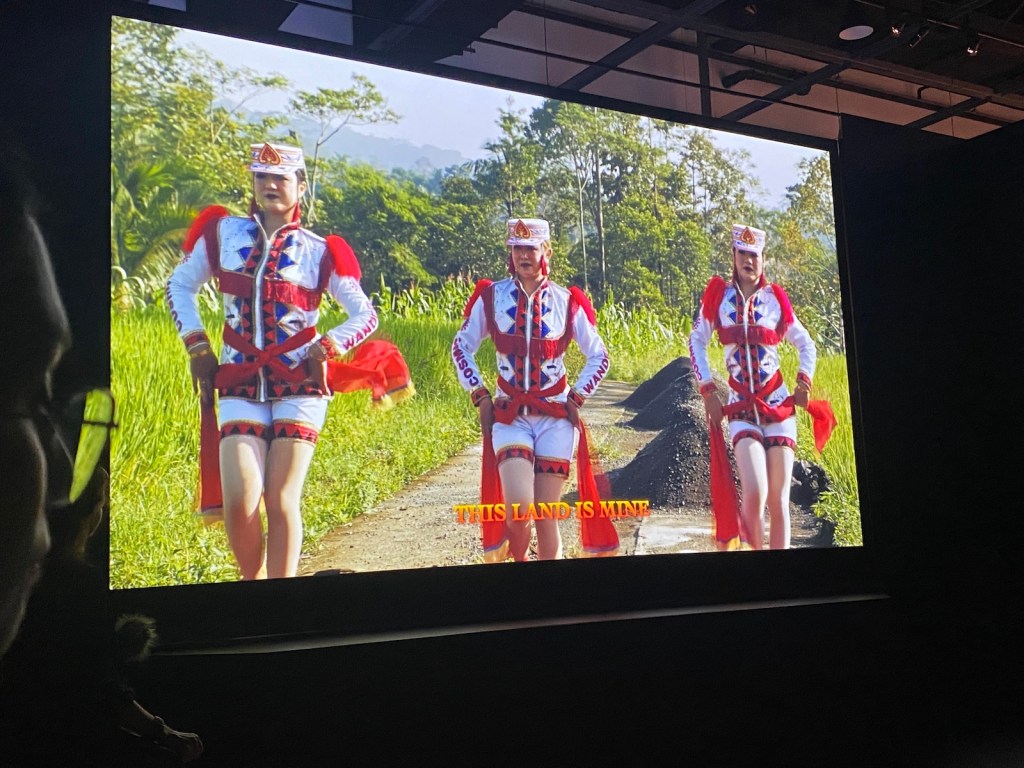

Visitors then move into, and through, a four-channel video by Agnieszka Polska (Poland/Germany), with an immersive wall-painted mural by Udeido Collective (West Papua) off to a side room, transporting the visitor into a world of protest.

Moving deeper into UNSW’s lower galleries, walls become a lavish gold – riffing off this mineral so often mined as another form of colonialism, trade and pillage. It is a nod to museological conversations and responsibilities today. Peppering the contemporary works in this space are textiles and objects all labelled “Unrecorded maker” and a stunning new work by Quandamooka artist Megan Cope, who works in a military maps style as an act of decolonial cartography to challenge terra nullius.

Cope’s work has a nice synergy with an enormous painting by Afro-Caribbean artist Frank Bowling (UK/Guyana) at the entry to the exhibition at AGNSW, which explores the notion of drifting geographies, as echoes of Australia and Africa fade as they march across the canvas.

Other highlights at UNSW Galleries continue to explore narrative of trade with an impressive work by Bonita Ely (Australia), the incredible abstract “paintings” of Leila el Rayes (Australia), using common hardware nails to recreate patterns from her Palestinian and Egyptian heritage, and a room of works created by a group of artists – Elyas Alavi (Hazara, Afghanistan/Australia) with Hussein Shirzard (Afghanistan/Australia), Jim Hinton (Australia), John Hinton (Australia) and Alibaba Awrang (Afghanistan/US) – which explore the music and culture bought by Cameleers to Australia, with neon rubab instruments alongside redacted texts from major tabloids, that in tandem speak of untold and/or censored histories.

The tone is dramatically different here and we are encouraged to rethink and recontextualise knowledge – which is perfectly suited to this learning institution, as is the hang of artworks at the Chau Chak Wing Museum. There 20 artists are show for the venue’s debut presentation, centreed around the narrative of truth-telling.

A sure highlight at CCWM is the video work by Choy Ka Fai (Singapore/Germany) that delves into coloniality, dance and trance culture in Asia via the band IndoRock, which was huge in the Netherlands. Part doco, part performance piece, it explores the power of mixed-racial culture as a form of agency from Dutch invasion to TikTok.

Downstairs at CCWM is an entire gallery turned over to the huge paintings of Juan Davila (Chile/Australia).

At Artspace, the artist r e a (Gamilaraay/Wailwan/Biripi, Australia) offers a guiding work for this Biennale – a text piece on the exterior of the building and new lower gallery, which is visible from the street and communicates with community. It depicts the words for “sun” in the Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi languages, as well as the words SILENCE = DEATH and LAND = RIGHTS, a cycle as present as the rising and setting sun.

Highlights here continue with a series of unstretched paintings by Ukrainian artist Sana Shahmuradova Tanska, who responds to her experience of taking refuge in Cold War shelters plastered with old atomic war posters during the recent conflicts. They are incredibly powerful pieces.

Central to the gallery is a suite of pots by Adebunmi Gbadebo (US) made from soil from the rice plantation where ancestors were slaves, an act of reclaiming the earth that created so much violence.

Violence from conflict also features at AGNSW, as mentioned in WWII narrative but also a colonial atomic era, finishing with a suite of works that explore pioneers of feminist and queer histories. A stunning inclusion in this last space is a suite of paintings by Indonesian painter (and domestic worker) I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih (Murni).

The exhibition shifts tone here and is perhaps the most political among Biennale venues. There are so many highlights across this incredible hang. Among them is a suite of works by Francisco Toledo – known as El Maestro Mexico, and one of the first Mexican artists to proudly present their First Nations heritage – again the curators always pulling us back to that through-line and legacies of resistance.

The MCA continues the big topics, touching on our climate emergency and doomsday narratives. The Biennale’s title spikes a vision of a scorching world and the inclusion of William Strutt’s (UK) huge colonial painting of Victoria burning in 1851 is a reminder of the deep embedding of apocalyptic fear in the Australian psyche – not just as a contemporary narrative.

It is further played out by Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg (Australia) with their filmic montage Doom, which speaks to our schools’ understanding of lived disasters thanks to cinema. There is a kind of weird pleasure watching its catastrophes roll along, a critique on how tragedy has become familiar and eventually entertainment.

MCA has also activated their large lower gallery for the Biennale exhibition, and standout works in this space include an impressive corner painting by Kirtika Kain (India/Australia) and Malaysian artist Anne Samat’s large beaded and woven installation blending traditional crafts with humble and everyday objects.

Exhausting – yes. Stimulating – yes. Walking away from this 24th Biennale of Sydney I feel renewed in the biennale exhibition format, introduced to fresh art but placing it in the context of a shared narrative of making here, now.

Take your time over the coming weeks to see this exhibition across all its venues. There are no duds here.

Ten Thousand Suns, 24th Biennale of Sydney (2024)

Presented at Art Gallery of New South Wales, Artspace, Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, UNSW Galleries and White Bay Power Station.

Curators: Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero

9 March to 10 June

Free

This edition of the Biennale of Sydney marks its 50th anniversary year.