Most of us seasoned gallery-goers feel like we’ve seen a thousand Impressionism exhibitions, in part because such images are part of our popular collective culture – used on placemats, in school books, posters and advertising, such as 1980’s Kit-Kat commercial of Frederick McCubbin’s On the Wallaby Track (1896).

It echoes another iconic McCubbin painting, The Pioneer (1904), which wraps up the exhibition She-Oak and Sunlight: Australian Impressionism – along with Tom Roberts’ A break away! (1891), Sheering the Rams (1890) and Bailed Up (1895), Arthur Streeton’s Fire’s On (1891) and McCubbin’s A bush burial (1890) and Down on His Luck (1889) – a kind of blockbuster-within-a-blockbuster moment.

They wrap up one thread of this exhibition in a way that’s expected: these paintings have constructed a narrative of Australian life, grand in scale, embedded in the landscape, essentially hard and physical, and romantic in sentiment.

However, it is where this exhibition, curated by Dr Anne Gray AM, starts – and how it deviates from that well-trodden path – that captured our interest more: with the inclusion of women artists who were also working in an Impressionist style alongside the celebrated coterie of male artists, and often sidelined by history.

Artists such as Iso Rae, May Vale, Jane Price, Jane Sutherland, Ina Gregory May Moore, Ethel Carrick, Elizabeth Mahony, Violet Teague, Grace Joel, and Alice Mills are given solid footing in this narrative.

This premise is established from the outset in the exhibition, with the first wall of paintings that viewers encounter presenting a grid of portraits of the Australian Impressionists – male and female indiscriminately.

Of particular note is the central section of the exhibition that looks at the almost mythical artists’ camps at Darebin and Gardiners Creek, Box Hill and Mentone, followed by paintings made at Eaglemont and its surrounds – all outside Melbourne. These are the works that people love, luscious landscapes bathed in light.

The women (thanks to conservative conventions of the day) could not camp overnight with their male colleagues and partners, but would take day trips to the camps to paint – Sutherland and Price in particular embraced this ritual.

Of note is Sutherland’s painting Obstruction, Box Hill, which shows a girl barred by a cow, uncertain whether to advance or retreat. It has been suggested that the subject of this painting could be a metaphor for the barriers encountered by women artists at the time.

Sutherland was a leading artist in Melbourne during the late 19th century, studying at the National Gallery School alongside McCubbin and Roberts, and sharing a studio with Clara Southern at Grosvenor Chambers (the first custom-built complex of artists’ studios in Australia) where the pair painted and taught art.

The exhibition has also been curated to placed Australian Impressionism within the context of European Impressionism, often resting upon pairings of works. One such pairing is Edouard Manet’s The ship’s deck (1860) with Tom Roberts Coming South (1886); another is James McNeill Whistler’s The mustard seller (La Marchande de moutarde) (1858) with Tom Roberts’ The Chinese cook shop c. 1887.

Whistler’s work was influential on the development of Impressionism in Australia, here depicting a working-class woman framed by multiple doorways against a dark interior – a device that Roberts picks up on in The Chinese cook shop.

The juxtapositions have been drawn from the NGV Collection – works by Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, James Abbott McNeill Whistler and others – and is a savvy bit of programming ahead of the NGV’s major blockbuster, French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which opens 4 June and overlaps with this exhibition.

A sure highlight of She-Oak and Sunlight – a real treasure for any fan of this Australian genre – is a small room of ‘9 by 5’s’ which mirrors the hang of The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition that opened on 17 August 1889 at Buxton’s Art Gallery, Swanston Street, Melbourne. The title referred to the dimensions of the wooden panels on which several of the works were painted – nine by five inches (23 x 12.5 cm) – or the size of a cigar box lid.

Installation view, 9 by 5’s presentation in She-Oak and Sunlight, NGV Australia. Photo ArtsHub.

It is a luscious salon hang on deep red walls, setting off these little jewels of light. Music compliments the works, which I understand was a favoured piece that Tom Roberts was constantly trying to master.

Tom Roberts, Charles Conder and Arthur Streeton were behind that original exhibition, explaining in the catalogue: ‘An effect is only momentary; so an impressionist tries to find his place. Two half hours are never alike … So in these works, it has been the object of the artist to render faithfully, and thus obtain first records of effects widely differing, and often of very fleeting character’.

Overall, the unifying aspect to this exhibition of more than 250 artworks drawn from major public and private collections around Australia, is the notion of place. It is interesting to consider in the context of our own times, and our increased awareness of the importance of Country.

The NGV says, ‘It is important to recognise that the visions of recently arrived artists were imposed over the culture, experiences and stories of First Nations peoples, whose deep connections to Country were disregarded.’

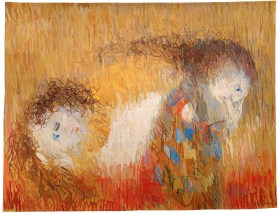

We see this demonstrated most clearly in that last ‘blockbuster room’, which places a suite of works by Wurundjeri artist William Barak, made around the same time, shoulder-to-shoulder with Roberts, Streeton, McCubbin and Condor.

Installation view of William Barak’s works in sight of Frederick McCubbin’s The Pioneer (2004). NGV Australia, 2021. Photo ArtsHub.

The gallery writes: ‘The stylistic innovation associated with Australian Impressionism has often led to the positioning of the movement as “Australia’s first school of art” … The Australian Impressionists sought to forge a connection with a place in which they had only recently arrived. At the same time, First Peoples in south-eastern Australia – where the Australian Impressionists were working – continued to make art enriched by their innate connection to and knowledge of Country. Viewed side by side, their work is testament to the complex, challenging, and often tragic relationship between art and identity in Australia.’

Barak’s drawings are stunning.

While the design of the exhibition feels tight, lacking a certain finesse in places, I was deeply surprised by how much I gained from this exhibition in terms of rethinking known narratives and expanding upon a much-loved Australian genre. It is definitely worth a look before you head into the splashy ‘off-shore’ version of Impressionism, soon to open.

4 stars: ★★★★

She-Oak and Sunlight: Australian Impressionism

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Fed Square

2 April – 22 August

Ticketed: $26 Adult / $24 Concession / $8 Child