Born in Queensland, Richard Bell did not immediately choose to be an artist, despite his parents both growing up with painting. But when he turned to art at age 31, it was explosive.

A survey exhibition of Bell’s work, You can go now, curated by Clothilde Bullen for the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), is just that – inflammatory. This suite of paintings seemingly ‘shout’ off the walls, begging the audience to stop in their tracks, to stop being complacent and to think outside their normal spheres of thought.

Bell’s belief is that we all play a role in change and reconciliation and that it starts with acknowledging certain truths.

The exhibition is split across the gallery’s foyer, and its two lower spaces. The earliest work in the show was created in 1992, a suite of photographs rewriting hope for Australia’s future – Ministry Kids (Children’s Parliament) – photographs of First Nations youth assign various political portfolios of leadership.

Read: Q&A Richard Bell: Art and activism 30 years on

We don’t see a lot of photography across Bell’s career, although he is fond of video in a short punchy format. We start to get a feel, however, of his painterly style with the early work, Devine Inspiration (1993), introducing his use of text in a graphic genre, as well as his penchant for appropriation.

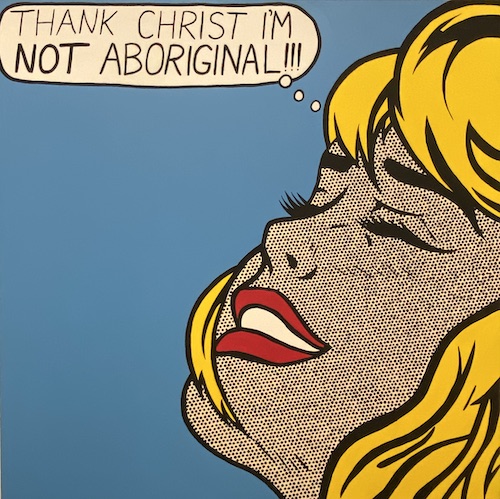

This is bought to life in a series of paintings, Made Men, that dominate the space and appropriate Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic pop portraits, replacing their ‘bubble quotes’ with Bell’s alarming take: ‘Thank Christ I’m not Aboriginal!!!’, ‘Thank Christ I’m not a Muslim…’, and ‘’Thank Christ I’m not a refugee!’. Lichtenstein’s blonde-haired Shipboard Girl, thanks to Bell, is now a blak-skinned sister.

Richard Bell, The Peckin’ Order, 2007.

Bell has often used appropriation as a mode for re-writing the past. We see it again with his painting, Vincent an’ Gough (From Little Things Good Things Grow) (2017), which takes its cue from Mervyn Bishop’s famous photograph of former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring soil into the hands of traditional land owner Vincent Lingiari in the Northern Territory in 1975, and which has become a masthead if you like, for Aboriginal land rights.

Land Rights are a persist theme across the exhibition – from the powerful painting, A property dispute is turned into a race debate (2019), where a map of Australia floats on a bloody field of colour – to Bell’s most celebrated and internationally recognised project, Embassy (2013–ongoing) (pictured top) – a pop-up Army issue style tent usurped as a forum for activist-toned discussions.

installation view Richard Bell exhibition at MCA, including the painting Vincent an’ Gough (From Little Things Good Things Grow) (2017). Photo ArtsHub.

In a nutshell, Embassy pays tribute to the inaugural embassy of 1972 on the lawns of Old Parliament House – paying it forward – as a contemporary site for dialogue, sharing and understanding. Bell has showed this project in Canada, New York and Venice, among other locations, extending awareness of the truths around First Nations histories.

It dominates the white cube space of the MCA, and around its edges catching our eye are signs of protest, placards that say ‘white invaders you are living on stolen land’ and ‘If you can’t let me live Aboriginal why! Preach democracy.’

There is no mincing of words here.

In this same space, Bell’s most recent work purchased this year by the National Gallery of Australia, From Little Things, Big Things Grow (2020) picks up on that title from his riff of Bishops’ Whitlam moment, pulling it into a contemporary context with a dense crowd brandishing placards in response to the wave of BLM (Black Lives Matter) protests last year.

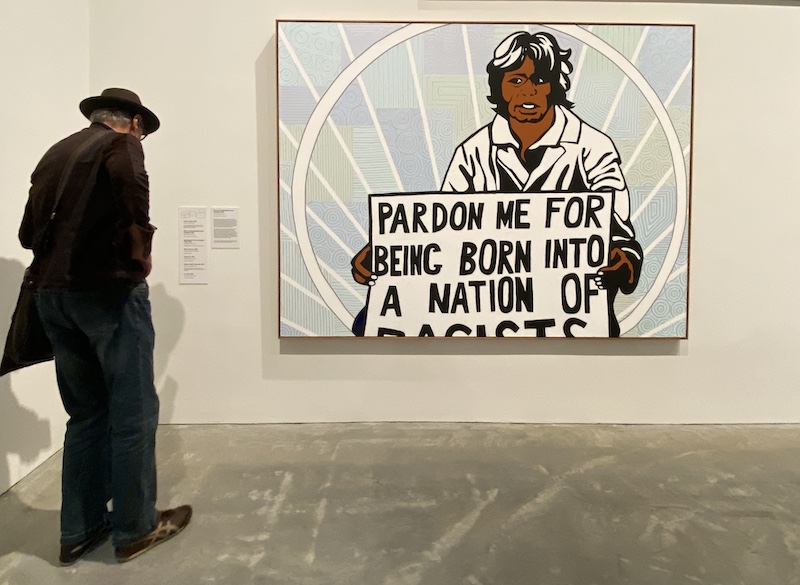

Suturing live protest and protest art is seamless for Bell. We only need to reach back to yet another painting, Foley vs The Springboks (Lone Portestor) (2012) that captures the 1971 South African Springbok rugby tour to Australia. It was an all-white team, and apartheid was still raging as an accepted policy.

In this painting, Bell appropriates a photograph taken of Aboriginal activist and friend Gary Foley, who demonstrated outside the Springboks’ hotel in Sydney; his sign reads ‘Pardon me for being born into a nation of racists.’

Installation view Foley vs The Springboks (Lone Portestor) at MCA. Photo ArtsHub.

What this painting does, Embassy does and his Bell’s 2020 BLM works do, is put Australia in a global context.

Embassy is backed by a salon hang that includes the works Colour Theory (2012), Australian Arts It’s an Aboriginal Thing (2006), Bell’s Theorem (2002), among others. It continues with the enormous painting, Peace Heals, War Kills (Big Ass Mutha Fuckin Mural) 2011, created in collaboration with Emory Douglas USA, who was Minister of Culture for Black Panthers Party (1967-1982), and who also turned to graphic posters to illustrate his doctrines.

Protest art can often be tough; it can often isolate in its hardcore politics rather than pull people into greater understanding and acceptance. Bell’s work has never suffered this fate. Its simple graphics and high chroma palette engages through humour and an almost casual style of riffing off blunders. For some detractors this bravado has been a point of criticism. But, hey, it works. Bell’s outpourings are incredibly popular.

This show is a must for any generation, and most definitely for an audience who wants to better understand the paths and blockages to reconciliation.

4.5 out of 5 stars ★★★★☆

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

4 June – 29 August 2021

Free