Conversations around cultural appropriation are often fraught with difficulties, but Tony Albert’s latest exhibition, Remark, tackles this topic with nuance and candour.

Presented by Sullivan+Strumpf at its recently established Melbourne gallery, this new body of work expands on Albert’s ongoing inquiry into the appropriation of Indigenous Australian iconography in domestic design and decor.

Remark is a continuation of last year’s Conversations with Margaret Preston exhibition, which saw Albert critically engage with the oeuvre of the acclaimed modernist painter and printmaker Margaret Preston.

Preston, who died in 1963, was one of the first non-Indigenous Australian artists to incorporate Indigenous Australian designs and motifs in her practice as part of her push to create a national visual identity.

Although her intentions may have been positive, Preston’s use of Indigenous imagery in her work opened the floodgates to a period of unrestrained cultural appropriation in design practices, reaching its peak in the 1950s and 1960s. During this period, objects containing crude and reductive representations of Aboriginal Australian people and their culture flooded the consumer goods market, ornamenting the sides of tea towels, matchboxes, ashtrays, coasters and a multitude of other mass produced items.

These kitsch objects, termed by Albert as ‘Aboriginalia’, popularised a reductive view of Aboriginality in white Australia, one that continues to breathe life into racist tropes today. In Remark, Albert draws upon his vast personal collection of Aboriginalia to create a new body of work that explores this tense relationship between ownership and appropriation.

Read: Q&A: Indigenous Artist Tony Albert on appropriation, identity and Margaret Preston

One of the first works to engage the viewer upon entrance into the gallery is Rebirth After the Fire (2022), a piece that sees Albert reference Preston’s woodcut compositions with unmistakable familiarity. What initially appears to be a seemingly innocuous painting of proteas becomes much more sinister when the viewer realises that the flower spikes have not been painted on at all, but have been fashioned out of hundreds of pieces of discarded ephemera.

Albert’s process of using appropriated Indigenous imagery, bodies and faces to create these ostensibly demure still lifes is a considered move. As we can see in the Remark Still Life (2022) and Remark (Modern Designer Vase) (2022) series, the juxtaposition of these now-offensive objects against ordinary suburban backgrounds is a way for Albert to break the illusion of domestic respectability that had once shielded these objects from criticism.

For Albert, this is an act of reclamation. By removing these pieces of Aboriginalia from their original contexts (that is, white suburban homes) and repositioning them in contemporaneity, Albert effectively repatriates these objects and liberates them from their painful origins.

Albert’s critique of the aestheticisation of Indigenous Australian culture continues throughout the exhibition. In Decorate (2022), Confetti Culture (2022) and Design (2022), the artist parodies the self-serving and exploitative nature of the commodification of his culture. With his characteristic wit, Albert spells out (quite literally) how Indigenous culture has been routinely pulled apart and scattered for superficial purposes.

The consequence of this, Albert suggests, is the proliferation of a popular culture in which First Nations people are seen, but not heard. What does it say about our society at large, he asks, when we choose to interact with Indigenous culture and people only to the extent that they complement and adorn our own lives?

One of the defining features of Albert’s practice is his sense of playfulness. While there is certainly a playful overtone to the exhibition, Albert is careful not to understate the damaging and painful legacies of misrepresentation and racist mimicry.

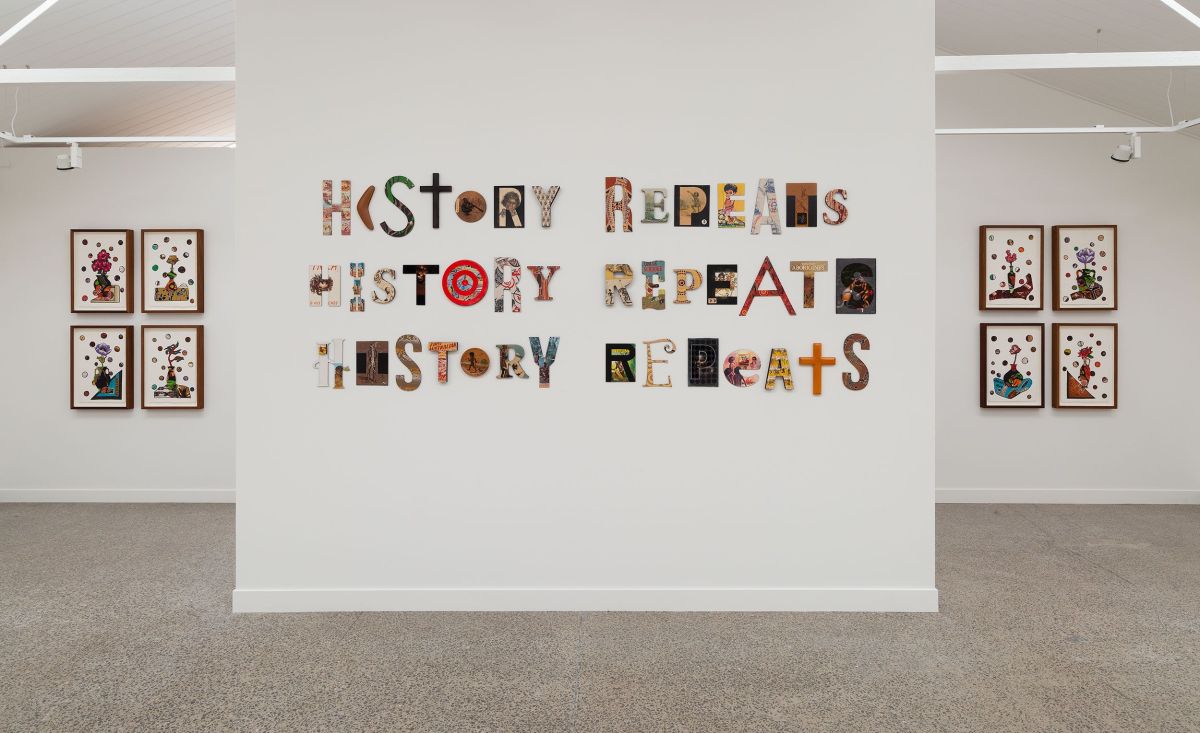

Throughout the exhibition, Albert uses images of weaponry and hunting to allude to the oppressive nature of appropriation. In Hunter (2022), he utilises vintage fabric to illustrate a scene of two Aboriginal men hunting kangaroos and, in History Repeats (2022), the artist superimposes a bullseye onto a piece of vintage paraphernalia to spell out the letter ‘o’. By recontextualising these words and objects, Albert subverts the vulgar stereotypes that precipitate depictions of Aboriginal Australian men as thuggish hunters and asks us to reconsider who, and what, is ultimately being preyed upon in these scenarios.

These moments of critical reflection are central to the exhibition, and Albert makes it clear to us that while these moments may be uncomfortable to experience, they are essential if we really want to be serious about reconciliation. As Albert spells out in History Repeats (2022), the only way we can guard ourselves against the future repetition of historic injustices is by confronting them together, as a community, head-on. This, ultimately, is Albert’s challenge to us all, and he warmly invites us to join him in the journey towards reconciliation.

Remark by Tony Albert will be on display at Sullivan+Strumpf Melbourne until 10 December 2022.