Speaking with Director Griffith University Art Museum, Angela Goddard, she said that when faced with the option of postponing the first Australian solo exhibition of acclaimed Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore with COVID uncertainty, there was no hesitation to go ahead.

She insists that you can still be ambitious with a major international show in our current times. We are the lucky beneficiaries of that decision.

Goddard has co-curated Turbulent Water with Wanda Nanibush, Curator of Indigenous Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (Canada) – a suite of documented performed works and video artworks by the First Nations artist.

Walking into the gallery the visitor passes by a suite of four videos that document Belmore’s performed works – perhaps overlooked in the first glance. But returning to them is important.

Here there is: X (2010), a performance that responds to the Kanehsatake Resistance of 1990 – a 78-day stand-off between protestors, Quebec police and the Canadian Army over a proposed golf course on Mohawk lands. Next there is Victorious (2008), which looks at the Canadian Prime Minister’s Statement of Apology on 11 June 2008, and acknowledgement of Indigenous survivors of the Indian Residential School system.

There is also Facing the Monumental (2012), a 150-year old indigenous red oak tree in Queen’s Park Toronto is ‘a living witness to colonisation’, and one of Belmore’s earliest performance works, Creation or Death: We Will Win (1991), performed in a colonial fort in the Havana Harbour, Cuba, and speaks to reclaiming territories.

As with most of Belmore’s work there is a political undercurrent – one which has a strong parallel with Australian First Nations narratives.

‘The artist’s body is a constant presence, enabling her to explore boundaries between public and private, power relations in contemporary society and the effects of colonisation on Indigenous people, especially women.’

– Curators, Turbulent Waters.

In the gallery, it is a very atmospheric experience. There are organic sound-bleeds and the rushing of water – which has an almost healing quality in Brisbane’s heat – and yet the first work encountered has no sound.

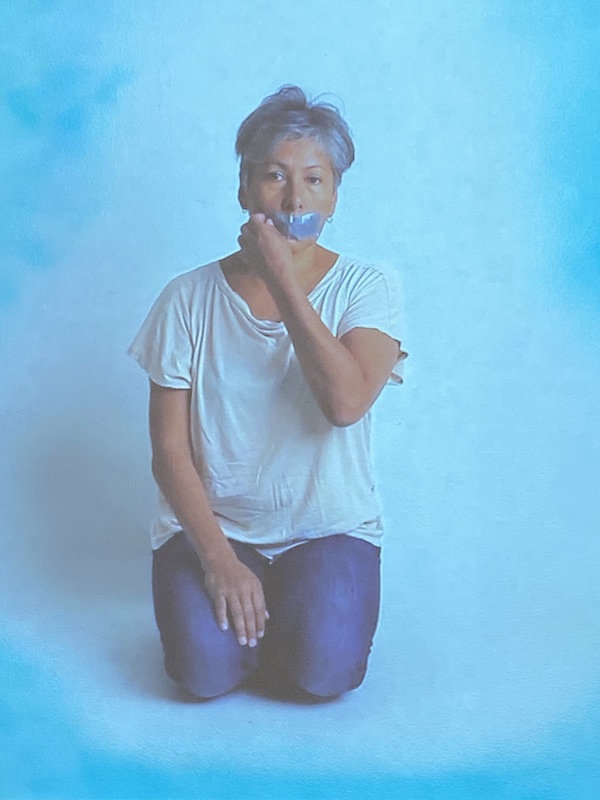

Apparition (2013) is screened onto an airbrushed blue wall. The artist sits central directly engaging the viewer. She covers her mouth with duct tape, and then removes it. The work is about the loss of Indigenous languages. Belmore says: ‘I do not speak Anishinaabemowin even though I grew up within it and around it … Apparition is an image of myself, a silent portrait of this loss.’

This work bears witness to the fact that Indian Residential Schools in Canadian Government sponsored religious schools that stole First Nations children from their communities for over 150 years. In her simple gesture, Belmore communicates across countries and cultures in a shared narrative.

Detail, Apparition (2013). Single-channel and latex paint. Collection: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Image courtesy the artist.

This is a tight show; just four works inside the gallery space. The second, Perimeter (2013), speaks of land and ownership.

Adopting an avatar role of the surveyor, Belmore physically traces the conceptual ‘boundary’ lines across Indigenous lands of Ontario – a landscape that moves between private nickel mining, colonial power structures, and the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek (Whitefish Lake) First Nation.

Belmore explains: ‘These spaces are linked by water through lakes, rivers and streams yet are subject to widely differing cultural and legal relationships.’

This connectivity through water is further played out with the work Fountain (pictured top), which was first unveiled when Belmore was Canada’s official representative at the Venice Biennale in 2005. For its showing in Brisbane, a scrim of rushing water (and reservoir below) has been constructed in the gallery, onto which the video is projected.

At one point in the film, the water seemingly turns to blood. It was filmed in the bleak industrial outskirts of a city, and again Belmore herself is the protagonist in a kind of elementary struggle against the forces.

It is an incredibly poignant viewing experience – a full sensorial engagement. Belmore uses video here in a very sculptural way, emphasised also by her incredible capacity to frame her images to hone our engagement.

Installation view: (L-R) Rebecca Belmore The Named and the Unnamed 2002 Video projection and light bulbs, Perimeter 2012 Video projection. Cinematography and editing: Darlene Naponse, Music: Julian Cote, produced by Pine Needle Productions. Photo ArtsHub.

Central to the exhibition is the video documentation, The Named and the Unnamed (2007), which aims to make visible a number of women who became ‘invisible’ from a corner in Vancouver (many of them Indigenous) and presumed murdered.

Belmore performed the work Vigil (2002) to honour them. For the installation, the performance is projected onto a field of lightbulbs – each one representing a women who went missing. There is this kind of push and pull between the physical space of the gallery and the virtual space of the film – metaphorically permeating time to a point in history and then pulling it into current conversations.

Read: Exhibition Review: Nicole Ellis, ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Overall, this exhibition has an elegance to it as a viewing experience. It is rigorous and respectful and yet it has a pace that allows contemplation. It seemingly washes over you as a viewer, entering every pore and setting deep in our conscious, and opening up thought.

Goddard’s choice in the show is particularly apt. The parallels are so very strong to an Australian Indigenous narrative, and it gives affirmation that these injustices are not in isolation.

Co-curator, Nanibush said Belmore’s work ‘…positions the viewer as a witness and encourages us all to face what is monumental.’ And it does. This is an important exhibition to catch if you are in Brisbane, especially in its capacity to break down isolationist tendency around a central conversation in contemporary society.

Belmore is a member of the Lac Seul First Nation (Anishinaabe), born in 1960 in Upsala, Canada. She currently lives and works in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Rating: 4 ½ stars out of 5 ★★★★☆

Rebecca Belmore: Turbulent Water

Co-curated by Angela Goddard and Wanda Nanibush

Griffith University Art Museum

25 March-19 June 2021

FREE