It would be fair to say that this exhibition both exhilarates and challenges local audiences.

From its pairing of a life-sized sculpture of a dead horse with a pastural, colonial-esq landscape outing pedophiles, to Hollywood’s blatant racist portrayals of those who are ‘different’, lurching canines, and finally a darkened gallery with a flotilla of white vinyl beanbags begging for longer engagement – there is no room for the passive or casual viewer when visiting Land Abounds.

The exhibition pairs the artworks of outspoken brothers, Abdul Abdullah and Abdul-Raham Abdullah, with the equally outspoken, Tracey Moffatt – who the brothers claim to have been an important influence on their work.

The pairing on first consideration is a little odd – more one dwelling in fandom and a kind of ‘CV stacking’ – but viewing the exhibition, it doesn’t take long to settle into the idea that ‘hey this makes sense’.

Ngununggula is situated in the old dairy of Retford Park, and just a short distance from its stables – the former home of Sydney’s Hordern family of department-store fame (built 1887) and then owned by James Fairfax of the newspaper dynasty (1964 – 2017). If ever there was a case for landed gentry this is it.

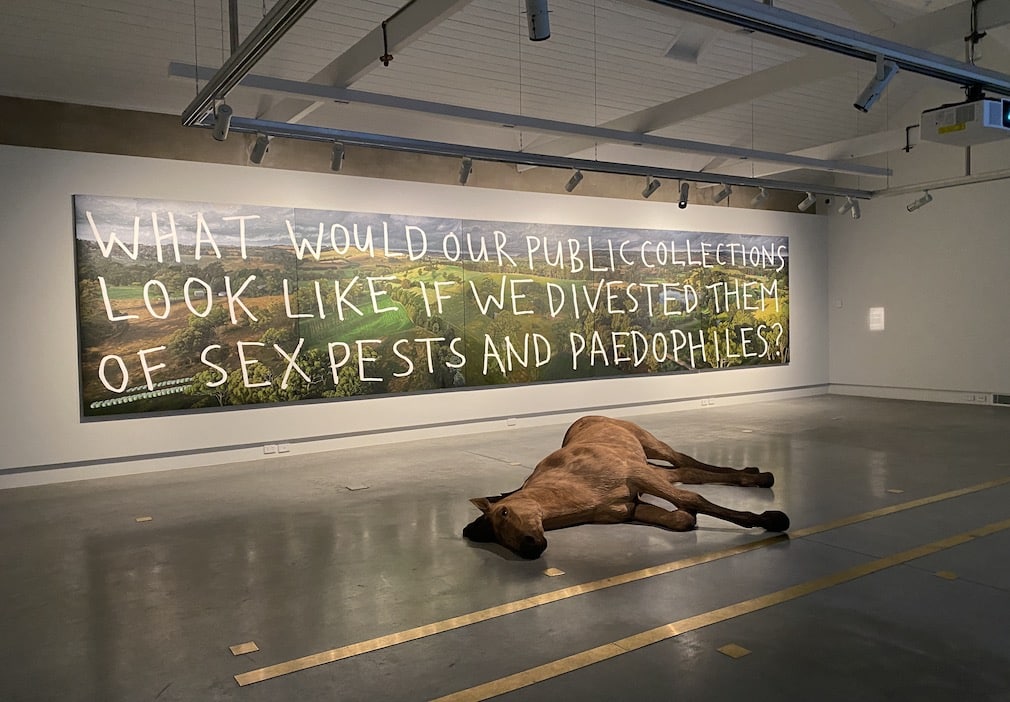

So Abdul Abdullah’s 10-metre painting of the neighbouring town of Berrima, titled Legacy assets, is a bird’s eye view of equine country, and riffs off Australia’s 19- and 20-century landscape painters, like Arthur Streeton and Joseph Lycett. We are nurtured into thinking this is what our landscape looks like.

Emblazoned upon the painting’s surface, aka placard style, is the statement: ‘WHAT WOULD OUR PUBLIC COLLECTIONS LOOK LIKE IF WE DIVESTED THEM OF SEX PESTS AND PAEDOPHILES?’ It picks up on a trend across museums globally to question gender equity, and loaded voyeuristic, power-based renditions of women within their collections, in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

There is no subtlty here. Abdul Abdullah prides himself on being an agitator – to call out, and to question. He points the finger without naming names.

Taking a slightly softer tone, but one that is equally an iron fist in a velvet glove, is Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s recent series of animals – including this new work, Dead Horse, carefully sculptured from ‘chestnut’ coloured timber.

Horse culture is huge in the Southern Highlands – as a play thing, but also with steep gentrified traditions. That Abdul-Rahman, a seventh-generation Australian Muslim, chooses a breed with roots from North America and West Asia is not lost, and offers up a more complex cultural symbol.

On another wall of the gallery sits Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg’s video montage Other (2007).

There is a nice segue to the next gallery, where Abdul-Rahman’s installation The Dogs is presented; three carved wooden dogs are grouped under hanging chandeliers. Traditionally dogs are considered unclean in Muslim culture, and further black dogs are thought to embody evil. He also references the use of dogs to patrol and protect.

He says: ‘This work juxtaposese the idea of territorial exclusion within a glittering, aspirational space described by the chandeliers. It promises an ideal that can’t be accessed, a gaudy beauty that belies the underlying violence of borders.’

That sense of compression and engagement works beautifully in this small gallery, where the viewer is forced into consideration of what this piece might mean, and how it makes them feel.

The tone shifts slightly for the last gallery space, darkened and disorientating with effect. Walking into the gallery, embroidered banners by Abdul Abdullah float in the space (titled Breach, Reach, Together 1 and Together 2), and seemingly part way to view Moffatt and Hillberg’s video Revolution, which unpicks power structures in Western history, constructed and nurtured into popular acceptance through film.

The hanging tapestries silhouette hand gestures of hope, of fear, of reaching in desperation for help, of solidarity and union. A flotilla of white vinyl beanbags seem to offer some navigation and beg one to drop and stop.

Overall, the exhibition does well in questioning how we construct narratives and perceptions of culture and tradition.

As Abdul-Rahman says of Moffat’s work: ‘She holds a mirror up to a social landscape that we all understand, exposing the dynamics of power that we consume and enact. The ways in which our works engage and respond to each other creates a multi-layered dialogue that always seems to come back to ideas of perception and power. What dictates our perceptions of the world, how are we perceived and how do we participate in that equation with autonomy.’

Land Abounds is presented from 28 May – 24 July 2022; free.

Ngungunggula, Southern Highlands Regional Gallery