We have been schooled to understand that hi-vis colours are a shorthand for an alert, to be seen or to expect danger ahead. It is not surprising then, that multidisciplinary artist Joan Ross has adopted hi-vis yellow as a signature for her probing artworks that warn of the perils of colonialism – and it’s a colour that punctuates her new survey exhibition titled Those trees came back to me in my dreams.

Commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) to recontextualise, and respond to its collection, Ross makes it effortless for the viewer to grasp the nuances of colonial history (and its repercussions) with casual ease.

Walking through this exhibition, Ross balances visual cues that are easily recognisable with a touch of humour – a device that pulls one into deeper – and often darker – conversations.

She spent months delving into the NPG’s collections, and viewers are witness to her passion for detail, archives and research. But this exhibition is far from stuffy and dusty. She has selected portraits and objects, which she has then paired with her own renditions – their very juxtaposition forcing a contemporary rethink.

Two incredible pairings in the first gallery are a great example and set the tone. Portrait of Captain James Cook RN (1782) by John Webber is paired with Ross’s rendition in crayon on lino, titled The day I discovered something in myself (2006). And, alongside it, is Webber’s portrait of William Bligh (c 1776), with Ross’s Phillip … a man with a mission (2006) – this time crayon on carpet. They sit opposite a salon hang of cameo portraits on a wall painted hi-vis yellow.

Co-curator of the exhibition Coby Edgar says that Ross asks, “do we really know these people?” and are we just upholding a legacy through these collection portraits, by perpetuating what we have been told.

This premise is carried from room to room, and across mediums from prints to videos to objects. It is a superbly curated journey across the four galleries.

In these first galleries, the visitor encounters Ross’ single-channel video, The great South Sea caterpillar (with animation and sound by Josh Raymond), and pieces such as Shopping for butterfly (2024) and The beginning of greed (2023) where two women passively fish in their canoes, while a colonial ship harvests a bulging haul in its nets. The idyllic setting is overshadowed by a sickly shade of doom and greed. It is a theme that is peppered across the exhibition, and the subtle repetition drums home a point.

The central gallery is perhaps the exhibition’s highlight. It focuses on a number of colonial women – drawn from both the NPG’s Collection and Ross’ oeuvre. In one – You were my biggest regret: diary entry 1806 (2022) – Ross makes herself the subject, acknowledging her own role as someone who lives here, and is part of this history that has razed the natural landscape in the verve of creating a new prosperous world.

It sits in tandem with Thomas Phillips’ portrait of Ellen Stirling (c 1828) and Henry Mundy’s portrait of Martha Kermode (c 1840), questioning the role of women in this history.

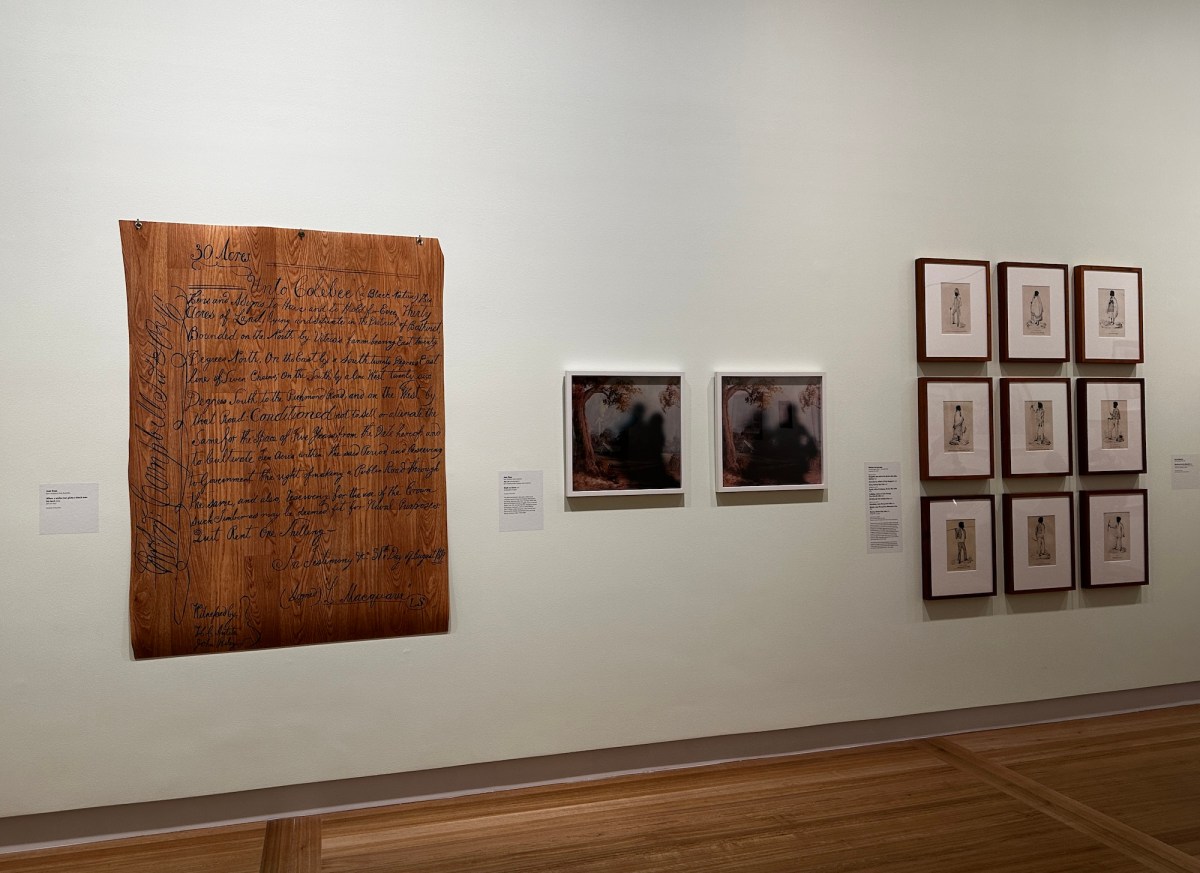

It is further played out in an interesting pairing of works, also in this space: a steroid-sized faux colonial deed (pen on vinyl) titled When a white man gives a black man his land (2006), alongside two portraits in the landscape, where the people have been almost redacted and rendered as anonymous.

Titled Shall we dance (2007), they were created with photographer Joy Lai and portray a Dharug woman, Maria Lock, who was the first Aboriginal woman to legally marry a colonist, and also receive a land grant – which is transcribed by Ross in the text.

There is also a suite of works here from Ross’ The Possession series (2023), which were made with the hero being a fictional perfume, and riffing off the vernacular of advertising. It is a message of desire, consumerism and also wealth – good meaty colonial topics that are just as current today.

They are paired with a vitrine containing Fake memories by Ross – aka plastic fob chains with lockets – and similar colonial personal keepsakes from the NPG collection.

The showstopper, however, is a wallpaper with three ceramics (made between 2010 and 2022), that seamlessly sit together as an installation. It is a fabulous presentation and shows just how cohesive Ross’ practice is across mediums.

In the final gallery is another short video, I give you a mountain (2018). It is just six-and-a-half minutes – and in sync with the kind of snapshot read that Ross offers through her work, but one that also is so digestible, that it begs an easy second, even third watch … and seduces viewers into a deeper dive.

Read: Exhibition review: Cats & Dogs, The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

The idea that hi-vis is a pathway for permission – aka don on a vest and you can get away with anything – is played out in her theatre of colonial characters, some drawn from history, some from the NPG collection, and others just players of the day, emphasising that we all enact a role in this pantomine of peril.

Overall the result is a dynamic and vibrant exhibition that coaxes audiences to think through some of society’s toughest topics with an ease and familiarity.

What I love is that the NPG has kept this exhibition free to view, especially as it is an institution that draws large school attendance and a broader gallery audience. The real nod, however, is owed to Ross. She has honed her visual language over several decades now, and the polish of presentation and deep engagement behind the work is so obvious viewing this show. She plays a very important role in the canon of Australian art history.

Joan Ross: Those trees came back to me in my dreams

Curated by Joan Ross, Coby Edgar, National Portrait Gallery, Emma Kindred

National Portrait Gallery

24 August to 2 February 2025

Free.