Recently, my friend posted on Instagram about how she had spent five painstaking hours removing all traces of cat hair from her paintings while preparing for a solo exhibition.

Art, I thought, can be like cooking, where much effort goes into removing all traces of the maker from the final product. This is not the case in Heide’s spectacularly strange exhibition, Hair Pieces, which explores both the functionality and aesthetics of hair. Numerous works in the collection list “human hair” as a material, either in the final product or in the creation of the work.

Spanning five decades and featuring both Australian and international artists, Hair Pieces is evocative and moving, squeamish and weird – a unique collection of works that explore hair as conduit and connection, as transcendent beyond the physical realm yet loaded with racial, political and gendered implications. The fragility of hair, the severing of hair, hair as care work and disembodied hair are all compelling themes.

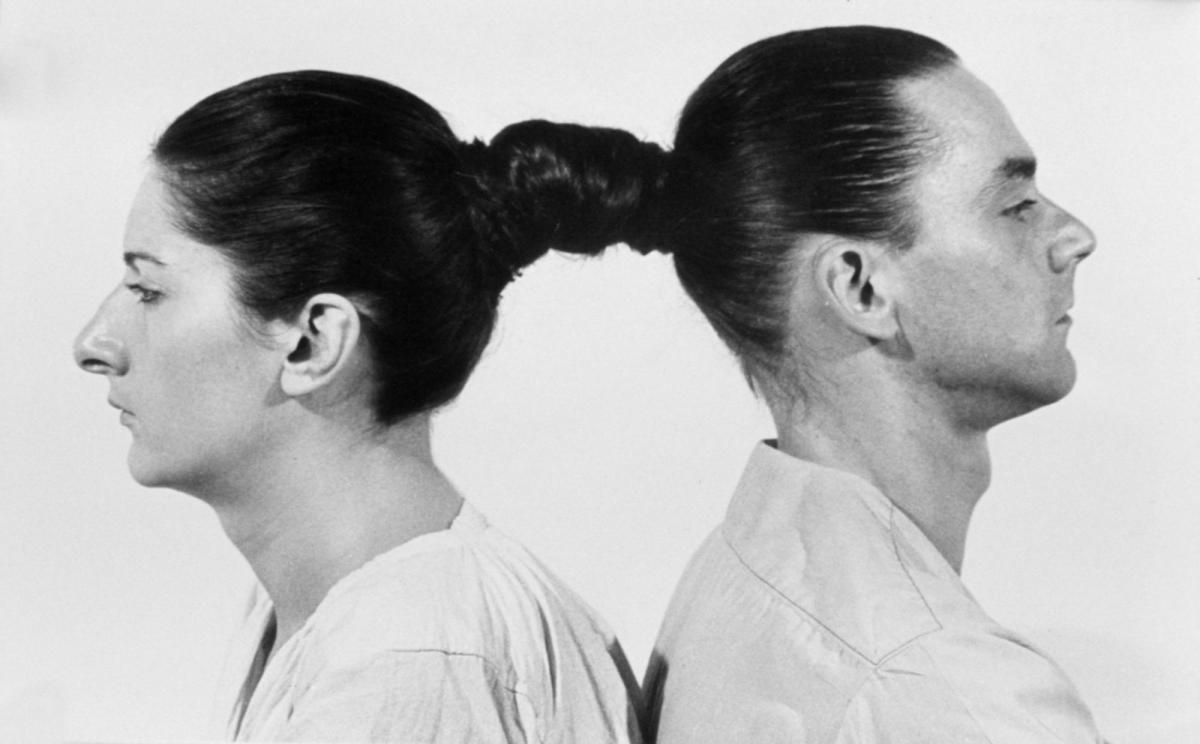

Some works, like Marina Abramović and Ulay’s video piece, Relation in Time (1977), depict hair as a binding substance, with the two artists fused together by their hair, seated back-to-back. The video, shot over 17 hours, shows the artists’, ‘growing discomfort, and the unravelling of the physical attachment between them’. The work reminds me of the contradictions of both hair and of physical relationships – strong yet delicate, beautiful and disgusting.

Zhang Hong Chun’s nine-metre-long, charcoal and graphite drawing of a braid, Life Strands (2004) is a detailed marvel. Representing, ‘a woman’s life cycle from the untangled radiance of youth, through … to the frail grey hair coming with age’. In this work and others throughout the exhibition, hair is a metaphor for the impermanence of the material body and a symbol of own mortality – the first thing to be carelessly snapped or chopped off, one of the last visually identifying substances clinging to a skeleton.

In Magna Mater (2020), Koorie/Wiradjuri artist S J Norman, ‘centres the body as a site of historical negotiation’. The video works feature 12 First Nations men having their hair brushed – 100 strokes a day over the same moon cycle. The used brushes lie below each film as poignant artefacts of this ritual, and act as, ‘contradistinctions with hair samples taken during anthropological expeditions’, that were used in, ‘dehumanising scientific procedures’ without consent. This stunning work is an example of how artists throughout the exhibition have used hair in their work to resist and subvert violent colonial histories.

Bidjara artist Christian Thompson claims that his grandmother used to send him on walks into the bush to see desert flowers in bloom, and gusts of desert wind would catch his hair, lifting it off his head – ‘I always thought about that kind of synergy that exists between the physical DNA of my body and the natural world, and how they are designed to be connected to each other’. His three-channel video work Heat (2010), captures this notion of entanglement, as each of his three subjects appears as though they may be swept away by the strands of their hair.

This is a provocative way to think of hair – as tendrils or receptors, as the linkage between our bodies and the atmosphere. Hair Pieces is full of these provocations, where artists and their subjects lend their bodies to the artwork, making it impossible to separate art from artist.

Read: Theatre review: The Importance of Being Earnest, fortyfivedownstairs

Hair Pieces invites us to consider the untapped potential of hair as a recycled resource, as a tool and as the root of both personal and cultural identity. It’s an ephemeral and powerful exhibition that transcends the boundaries of traditional art forms and spirits the viewer away to another world where hair is reimagined as a centrepiece, rather than mere decoration or DNA evidence. Hair Pieces is a suggestive collection of artworks that left me spellbound and introspective.

Hair Pieces curated by Melissa Keys, will be exhibited until 6 October at Heide Museum of Art.