The construction of a post-colonial Australia is captured through Radiate, an exhibition of cookware assemblages by Donna Marcus at Gold Coast’s Home of the Arts (HOTA). The artist, a mother of two and partner to architect Fred Cehak, is emerging as a matriarch of Queensland sculpture. This second significant survey of her artwork is curated by Sam Creyton. The first, Teamwork, was staged at Gold Coast City Art Gallery in 2001. Audiences residing in the south-east of the state may be familiar with her monumental sculpture, Steam (2006), an illuminated landmark permanently located in Brisbane Square.

From first glance, visitors may be mesmerised by the mass and variety of vintage utensils on display – from colanders to electric frypan lids. Most are aluminium, a material that is now maligned, but once presented a significant manufacturing industry in Australia. It was, like the artist, born in the 1960s. This unearthing of familiar forms from her childhood is infallibly evocative. They reflect hundreds of meals prepared and served, representing an understated yet integral role women have long played.

The assemblages mark the crossing of a threshold for our nation, which replaced the British pound with the Australian dollar in 1966. A progression from monoculturalism may be found in the cast vessels. The breaking out of the British culinary mould of meat and three vegetables can be contemplated when viewing the partitioned plates of Tempo (2021). The arrival of non-British migrants and refugees may be alluded to by the inclusion of Asian steamers in GABO (2022-23).

The artist allows audiences to discover beauty in a post-war merger between industrial and domestic aesthetics. Her embrace of the readymade may be read in light of the contested reassignment of the genre’s invention to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927), rather than Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). (During WWI, Freytag-Loringhoven, a Dada artist and poet, worked under the pseudonym Richard Mutt, the same name inscribed on the infamous Urinal attributed to Duchamp.) After WWII, a pivot in manufacturing led to a proliferation of mass-produced household items. Many were designed to lighten the load of domestic duties for women, some of whom had returned to the workforce to meet labour shortages created by conscription.

Many art historical references can be drawn out in Marcus’ works. Parity may be found between Marcus’ sets of square tins in Field (2016) and the, at times monumentally-scaled, installations of hollow metal boxes by minimalist Donald Judd (1928–1994).

A seductive element of this show is the combinations of colours that Marcus has elicited through amassing similar shapes. This can be observed in a set of six sun-like assemblages formed from triangular saucepans with bakelite knobs. Chronologically, the titles begin with Parlour (1997) and end with Patio (2021). The artist could be capturing how light falls in different parts of a domestic dwelling. This sentiment may be curatorially reinforced by the inclusion of one of two artworks not produced by Marcus, such as Roland Wakelin’s Down the Hills to Berry’s Bay (1916). The Post-Impressionist was renowned for his “lively colour”. However, this celebration of the vibrant colours afforded by anodisation can also be viewed through the minimalist lens once held to paintings and collages by Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015). Marcus’ Spare Room (2006) glistens with blue, red and pewter containers, with gradations of tone within each cluster.

SS Gabo, Berry’s Bay, Sydney (1917) by Percy Lindsay is the second in a pair of landscape paintings hung at the entrance of the exhibition. It depicts the vessel that Marcus’ mother grew up on as part of a family of salvagers. The steamship itself was eventually stripped for parts.

Arte Povera (poor art), which entails the repurposing of non-traditional art materials, countered minimalism in the 1960s. Elements of this exhibition meet the criteria for both camps. While the former may be considered less of a men’s club, Marcus’ salvaging, sorting and sequencing bears closer resemblance to craft processes, which second-wave feminists engaged, such as quilting and collage.

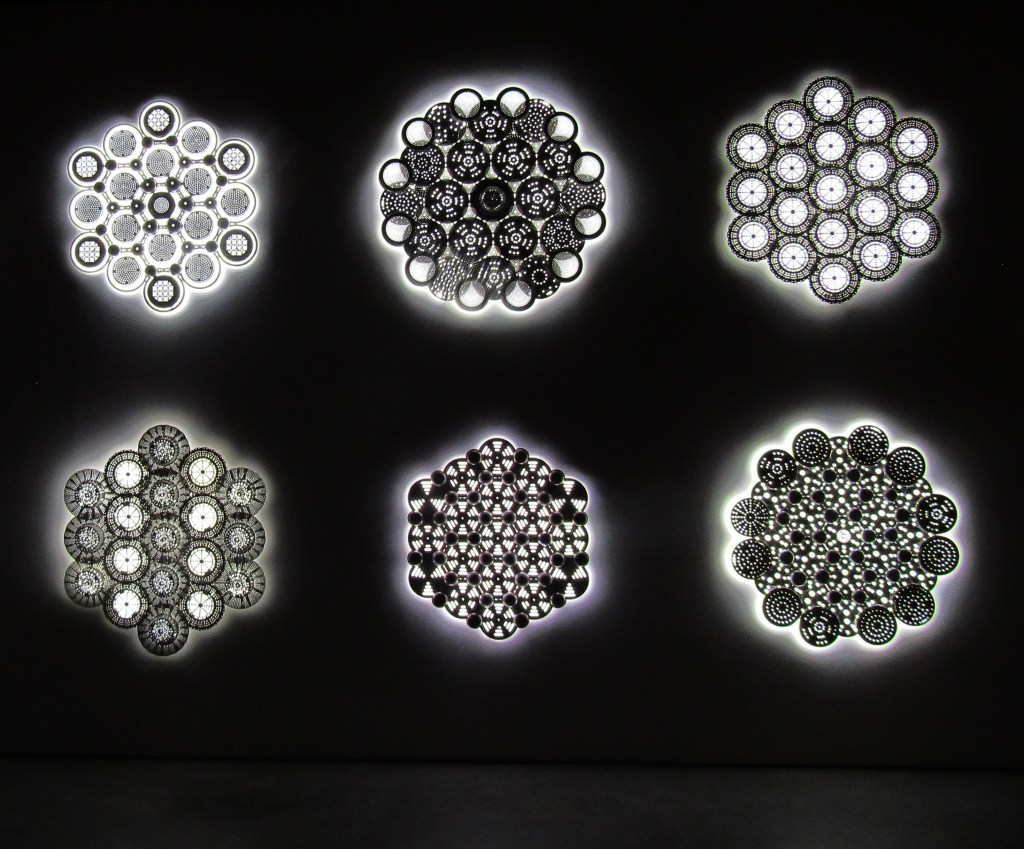

GABO (2022-23) is a series of sculptures primarily fashioned from steamers. The backlighting of these steel-reinforced structures creates a sense of fragility. During the Renaissance, lacework carried the memory of its geographic place of creation. Likewise, clues to the origin of each part may be found in its concatenation of holes.

Read: Exhibition review: Heavenly Bodies, James Makin Gallery

Radiate demonstrates Marcus’ compelling capacity to create organic compositions from machined components. This emphasises the humanity within the objects sourced from op shops, as though each were imprinted by its previous owner. An aspect of all the artworks – but especially apparent in the Tetris-esque arrangement of cupcake trays in 360 Degrees (2009) – is how the items scaffold one another. Each of the innumerable vessels played its part in feeding a generation. The exhibition pays homage to the women of the 1960s, who seeded the growth that has enabled our nation to flourish today.

Radiate is on view at HOTA until 28 April 2024; free entry.

This review is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.