Dianne Jones is an artist with an impressive back catalogue of distinctive photomedia works, many of which present direct challenges to mainstream ideals of Australian nationhood and its collective identity.

Since the early 2000s the artist has worked closely with archival images created by some of Australia’s most iconic photographic artists – notably names like Max Dupain and Harold Cazneaux – whose youthful, egalitarian evocations of ‘typical post-war Australian life’ are immediately recognisable to many Australian people.

In Jones’ latest solo exhibition – Dianne Jones | The Beach – curated by Abigail Moncrieff, we see those celebrated ‘images of Australia’ reworked to expose just how narrowly defined and downright false some of the narratives presented in those mid-century documentary-style images are.

Of course, artists like Dupain and Cazneaux were only capturing life as they saw it and experienced it at the time (in the 1940s to 1960s). But in inserting herself – as a Ballardong woman from Noongar Country – into their frames, the artist is able to imbue them with both subtle elements of humour and a biting sense of political critique.

Her entire Australian Photographs series – created in 2003, and seen in this solo show for the first time in its entirety – is installed along both sides of the gallery’s corridor space where they sit in apt dialogue with each other.

As we trace each image for evidence of the artist’s identity, when we locate her – perhaps she is reclined on the beach or posing on the street among other fashionable ‘Christian Dior’ ladies – we are reassured by the warmth of her smiles and her poise that she is totally comfortable being part of these ‘everyday Australian’ scenes.

Yet we know that Jones never actually stood in those places and, if she did, as an Aboriginal woman, she would have not have felt at home nor at ease in them at all. This is where the works begin to reveal their deeper meanings.

One particularly layered piece is a reworked version of Max Dupain’s famous photograph Meat Queue (1946). It shows Jones standing in for a rather affronted looking lady (from Dupain’s original work) as she waits in a long queue at a local butcher’s shop. Rather than assuming the obvious ‘tsk tsk’ expression of the lady in Dupain’s original, Jones’ Meat Queue character has an entirely different air. She stands with one hand on her hip, clutching her handbag across her chest with the other, and looking slightly irritated at having to endure a long wait ahead. But her expression is also saying, ‘You can imagine what it feels like to be stuck here in this immovable queue – right? But I for one am not going to let it get the better of me.’

It’s an image that makes you smile to yourself before you start to reflect on some of the serious injustices of Australia’s past.

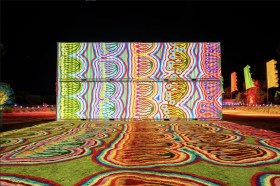

In a similar vein, Jones’ latest work – a floor-to-ceiling scale photomedia piece commissioned especially for this show – reveals even more ways in which the artist continues to respond (in a style both cheeky and defiant) to iconic artworks of the past.

This epic photomontage is titled Jones’ Beach Party (2024) and takes its cues from mid-century Australian artist Charles Meere’s work Australian Beach Pattern (1940) – a painting that continues to spur debate around how closely or not its aesthetic aligns with the Aryan ideals made popular in 1930s Nazi Germany.

In Jones’ version, instead of the young, white bodies shown in a series of strong athletic poses, it’s the artist and her extended family who are in the spotlight, enjoying a day out at the beach. The scene is deliberately set on Manjaree (Bathers Beach) in Walyalup/Fremantle, which is a site of great cultural significance and kinship for Noongar people, while also being the point of first contact with First Nations peoples made by British Naval Officer Captain Charles Fremantle on his mission to claim the west coast of Australia for the Crown in 1829.

Read: Exhibition review: Thinking together: Exchanges with the natural world, Bundanon

It’s a work brimming with political meaning, but it’s also infused with great happiness and joy – marking it as a fitting continuation of Jones’ investigations into how her identity as an Indigenous Australian woman intersects with societal ideas of nationhood, power hierarchies and structural inequalities.

Dianne Jones | The Beach exhibition runs until 20 April 2025 at Walyalup | Fremantle Arts Centre, 1 Finnerty Street, Fremantle, WA; free entry.