Among art administrators there is a cardinal rule, often left unspoken, that curators and content providers must remain distinct in their roles for an exhibition to be taken seriously. However, ask any artist who has facilitated a group show, especially from a marginalised community, and the response is fairly consistent. The latest in a series of collaborations between the collective Conscious Mic and Metro Arts, Ctrl + Alt + Delete: Reclaim, literally speaks to the desire to stake out some real estate, both with respect to the gallery and in the imaginings of South East Queensland art audiences.

Across the iterations of the annual showcase since Metro Arts made its move to Meanjin/Brisbane’s West End in 2020, there appears to be an algorithm that extends beyond the contributions by artist/curators Serge Ah-Wong and Bindimu Currie. The First Nations and Pasifika artists presented paintings and installations in successive years. Teleise Lēsa also returns, having rescaled another necklace to monumental proportions. In addition to ‘reclaiming’ geographic space, the theme has also been applied by some contributors to ‘the image of Blak bodies’ and narratives ‘people have tried to tell about us’.

While the names of the artists are far from household, audiences may find many aspects of their artworks familiar. Visitors old enough to remember IBM’s release of personal computers in the early 1980s, with the ‘hotkey’ combination from which Ctrl + Alt + Delete: Reclaim takes its title, are given plenty to reminisce. The period also gave rise to anonymous art collectives, a movement driven by the feminist Guerrilla Girls, who strove to address institutionalised sexism and racism. The promotional material for this exhibition similarly omits the names of individual contributors.

Subtly seductive, yet soothing as opposed to sinister, Currie’s woven Ngumbu Jarba (2018) calls for change through depicting a life-sized snake shedding. The multidisciplinary artist is a Gugu-Yalanji, Minyangbal and Gooreng Gooreng, woman with South Sea Islander heritage.

Teleise Lēsa, a New Zealand born artist and designer who identifies as Samoan, was a child when Jeff Koons rose to prominence with his oversized kitsch appropriations of the everyday. To many, Ula Nifo (2023) may carry greater cultural significance than the aforementioned commentary on rampant consumerism. ‘Ula’ meaning ‘necklace’ and ‘nifo’ meaning ‘tooth’, she has taken inspiration from this symbol of status. Traditionally worn by high chiefs, these pieces were carved from the teeth of sperm whales. The relatively recent migrant to Brisbane says she takes great pride in fashioning supersized homages to her homeland. This sculpture, in turn, imbues the gallery space with an almost hallowed atmosphere.

Similarly symbolic, but domestic in scale, is a playful presentation of resin and 3D printed kava bowls by Abraham Tongia, who undertook his Bachelor of Architecture at Auckland’s Unitec. A cluster of his vibrant non-utilitarian representations of the ceremonial vessels colonise a section of the gallery. Some are attached by the legs to the sides of their plinths, as though crawling from one to another. Tongia’s considerable skills in 3D modelling may be observed in the surfaces of the more intricate bowls. In others, where the forms are relatively simple, his capacity to cast with translucent, nuanced gradations of colour, is celebrated. Despite the technology attaining ubiquity in Australia over the past decade, 3D printing was patented in 1984. It first appeared in a gallery in the form of resin sculptures by Japanese technologist Masaki Fujihata in 1989.

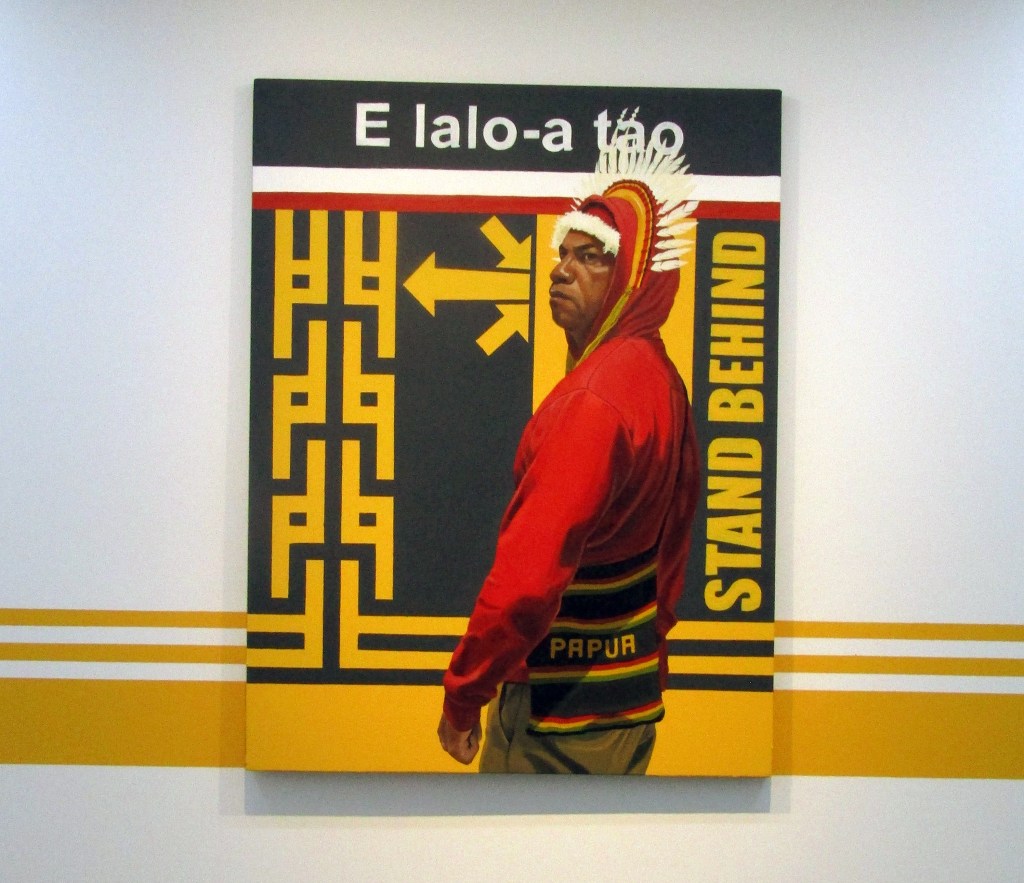

This sanctification of the space is further amplified by the seeming deification of a ‘migrant-settler‘, in Ah-Wong’s E lalo-a Tao (Remember) (2023). A graduate of Charles Darwin University, Ah-Wong and his family migrated to South East Queensland from Papua New Guinea. Through a combination of proficiency in figurative painting and integration of pattern, comparisons may be drawn to Kehinde Wiley. The, at times, controversial American artist of colour has been associated with the emergence of ‘post-racialism’. His being commissioned to paint former President Obama in 2018, by the National Portrait Gallery, maybe considered a career apex. However, Ah-Wong favours the abstract motifs of his people as opposed to the imagery of his oppressors. This distinction flavours the compositions with a powerful socialist aesthetic, which some audiences may have previously encountered in Soviet Propaganda posters.

The Ctrl + Alt + Delete series was conceived in 2018 to create visibility for this underrepresented community in the South East Queensland art sector. The skilled makers appear to present art in forms that are readily recognisable and, arguably, appealing to a middle-aged audience. During the 1980s, many of the concepts, aesthetics and technologies, may have been considered avant-garde. It was also a decade of significance for Australian politics, with the introduction of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act and the establishment of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

Read: Exhibition review: Data Relations, ACCA

While the exhibition may not break new ground, it does pose the question, ‘What has changed?’ The existence of this initiative which, according to Ah-Wong, serves to enable the ‘telling [of] our stories on our own terms’, would suggest that many issues remain salient. Above all, the project does enable the artists to occupy the cultural landscape, from which they have felt excluded. The other contributors include Jeremiah Nuenedorf, Rovel Hagos and Jori Etuale.

Ctrl Alt Delete: Reclaim

Metro Arts, Queensland

Ctrl Alt Delete: Reclaim will be on display until 4 February 2023.