Now in its 23rd year, this year’s exhibition and symposium were more interesting for the newest developments in Aboriginal art centre projects, such as films and multimedia, than it was for the fine paintings for which many of these art centres have become known.

Over the years one has come to expect a riot of colour, movement, shimmer and spiritual power when entering the galleries at Araluen. Unfortunately, that was not the experience this year. Desert Mob seems to have gone back to its previous self; a mixed bag of works by major, middle level and emerging artists.

There is some confusion amongst collectors and the art public as to the curatorial intent of Desert Mob. Over the years, it became increasingly a showcase of some of the best works by some of the most interesting artists, artists from local Alice Springs and as far as Balgo, over the border in Western Australia.

Many of these artists’ works have a demand greater than their output can supply, and collectors have to move fast to get their works in exhibition. Desert Mob thus became a kind of democratic collecting exhibition, where anyone could buy a good quality work by a great artist, often at a very good price.

While art centres entered work of their choosing, the staff at Araluen increased the demand for quality and particularly in the years 2008-2012, there were many truly excellent paintings in particular, as well as unusual three-dimensional works.

But this was never actually the aim of Desert Mob: it is an annual exhibition by Araluen in conjunction with Desart, the governing body of the central art centres. This is not, as has been misreported in the media, an exhibition where ‘mostly’ these artists are from art centres: they all are, it is their exhibition. It is not aimed at being a reflection, a survey show, of the annual best Aboriginal art, although that is a great curatorial idea, which should also be created.

And yet it does showcase, usually, as do commercial gallery and some award exhibitions, that there is a lot of good work being produced in art centres, despite again the misreporting on this fact in the media – an example of the lack of knowledge too often displayed about this major art movement of Australia.

A combination of factors: gallery pressure for the best works, the tragedy of the many deaths that have occurred over the past year in the APY Lands, and the time taken for mourning, and other commitments have definitely contributed to the lack of strong works this year. There are many unseen pressures on Aboriginal artists that we have little idea about.

The stand-out paintings were a sublime, mostly white canvas from Nora Wompi from Warlayirti Artists in Balgo; three small paintings from the gifted Sandy Brumby from Ninuku Arts; a large Bob Gibson from Tjarlirli; a stunning Ray Ken, Tjala Arts’ entry into the Art Gallery of Western Australia Indigenous Art Awards (with a price tag to match); and an equally large Barbara Moore, the other new stand out artist from Tjala, perhaps without the superb power of her usual medium-sized exhibiting works, but a solid work nonetheless. A vivid Kukula McDonald in her latest palette of lush green. The senior elder Pantjiti Lionel from Ernabella was impressive as was a Tjitjuna Andy and Ngunytjima Carroll ceramic work, whose fineness was exemplary.

Spinifex Artists have developed well in the past year, with notable works by female artists such as Anmanari Brown, formerly of Irrunytju and Papulankutja, and Estelle Hogan and Yarangka Thomas.

It was great to see a Roma Butler of the Minyma Kutjara Project, up and running from the troubled community of Irrunytju, a centerpiece community of much of the great art from the APY Lands that found itself embroiled in private dealer/art centre politics and has been without an art centre for some time.

Yet overall there were less works, and less quality works, than in previous years. It was significant to have a wall of men’s paintings from Tjungu Palya, but only the Bernard Tjalkuri stood out. The works from Papunya Tula Artists and Warlukurlangu were indeed quite wild, but few had the finesse of works seen in commercial galleries.

Unusually, it was not so much in the medium of painting, but in the subtler one of printmaking that was of major interest in this year’s Desert Mob. The late Tjilpi (respectful term for old man) Kunmanara (a name for someone who has passed away, meaning that which must not be spoken) Kankapankatja’s, of Kaltjiti Arts, final suite of prints, exhibited previously in a solo exhibition in Darwin, were extremely significant and intriguing. Created by Kankapankatja compulsively after he had a near-death experience, they were recollections from his pre-contact youth. A significant ethno-botanist, with extensive knowledge and integral passion for his country and culture, they are a unique set of works creating an important lasting document. Their black and grey palette gives them an austerity and subtlety that recalls cave paintings, as noted by Kieran Finnane in her excellent article on the exhibition and symposium for the Alice Springs News. They were a complete change from the artist’s previous work, which focused heavily on his botanical knowledge, and were often in a palette of brighter colours.

Papulankutja and Mimili Arts also exhibited notable prints.

Desert Mob is significantly a place for experimentation, where art centres can enter their emerging artists, or their established artists who may be trying something new. Of these, the light boxes from Warakurna Artists were the most successful. They fused the strong Indigenous skills of painting, craft and storytelling with a focus on recent and past history. As explorations of space, they work outside Western borders, just as paintings often do; some of the sides of the light boxes continued the story in the artists’ language (usually Ngaanyatjarra) and with imagery. They depict such significant events as the Circus Waters event, a horrific tale from Australia’s often bloody past, wherein Aboriginal people were shot and prospectors speared, and more recent events such as the arrival in the community of a mobile phone tower and ICTV. While they were naïve in painting style and didn’t contain the sophistication that Warakurna painters usually display, and they weren’t aimed towards the fine art collector who collects beautiful, spiritually resonant works, they are nonetheless an important body of works documenting a more recent history.

The Tjanpi Desert Weavers have been increasingly busy over the last year, with major exhibitions including the incredible installation they created, one of four, for the MCA’s String Theory exhibition. Such a work should have been included here; instead there were some beautiful baskets, but nothing as significant as that work.

More unusual was the entry from the Greenbush Art Group, representing prison artists, who are becoming even more imaginative with each year in their use of found objects. Skilled sculptures of dreamtime totemic echidnas, rainbow serpents and goannas were created out of bike parts, car parts, and even frying pans, combined with feathers.

Equally impressive in the three-dimensional works were Rhonda Sharpe and Marlene Rubuntja of Yarrenyty Arltere, and their new artist Louise Robertson. Sharpe’s new work is an astounding series of aliens; tall, thin, eerie creatures, from the art centre located in an Alice Springs town camp that lies at the foot of the White Dog or Devil Dreaming at the beginning of the Western MacDonnell Ranges, which produces a kind of desert gothic art with flashes of almost psychedelic colour. The YA artists have become increasingly conceptual in their use of three-dimensional story telling: Sharpe’s Aliens series are entitled ‘looking, searching’; for what, the viewer wonders? These works are an example of the result the making of short films by many of the art centres are having, as highlighted in the Desert Mob symposium. They are providing a new vehicle for fusing traditional storytelling, art making, creation, education, philosophy and ecology into powerful conduits for both us, the viewer, and they, the creator. The films from Mimili, in particular, which will be put on their website, showed how powerful the combination of Aboriginal culture and great cinematography and editing can be.

While the films are being made in collaboration with non-Indigenous filmmakers, there is no doubt they are having an impact on the painters, weavers, and creators of three-dimensional works. This is an example of a way forward, to sustain freshness and to invigorate, for all generations of artists.

Desert MobAraluen Arts Centre, Alice Springs

Until 20 October 2013

View an online gallery of the works: www.desart.com.au/galleries

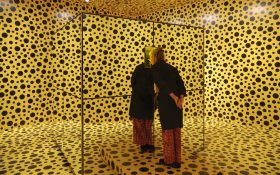

Desert Mob installation view. Image: Lisa Hatzimihail

Courtesy: Araluen Arts Centre