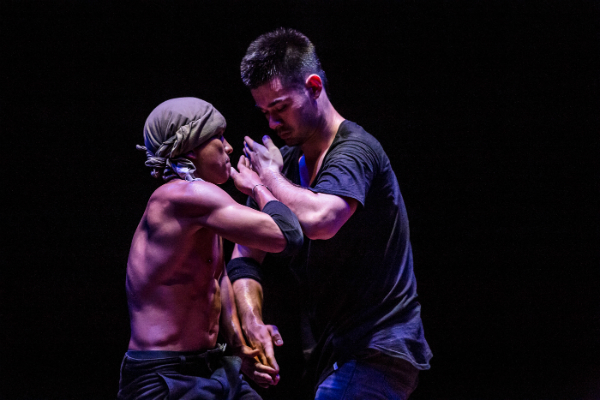

The Farm’s Cockfight. Image by Kate Holmes.

Like any arts festival, Melbourne’s contemporary dance festival Dance Massive is best explored by diving in headfirst. Seeing an array of works gives greater perspective on the program, and keener awareness of the choreographic trends and concerns on show.

Read: Dance Massive 2015: collected reviews

The main drawback of seeing as much work as possible over the festival’s 13 days (other than the inevitable festival fatigue) means there’s less time for detailed and considered critical responses to the work on show.

The solution? Snapshot reviews that give a clear sense of each work’s strengths and aesthetics, which we’ll update frequently in the coming days.

The Farm’s Cockfight

Meat Market, North Melbourne

24-26 March

3 ½ stars

Intergenerational tensions and masculine insecurities are explored with dramatic physicality in Cockfight, a dance theatre piece created by Gold Coast company The Farm in association with NORPA and Performing Lines.

Set in a mundane office, the work sees Gavin Webber (co-director) and Joshua Thomson (co-director/set designer) battling for supremacy with every weapon at their disposal, from petty control and dismissal tactics, to stag-like clashes in which office chairs replace antlers.

At times broadly comedic, with a Buster Keaton-esque physicality on show, Cockfight switches effortlessly to moments of beauty and poignancy, strongly assisted by Luke Smiles’ sound design, which integrates songs by Le Tigre and Cat Stevens into his moody and evocative score. Mark Howett’s lighting design is also noteworthy; his skill is perhaps best displayed in a scene reminiscent of Blade Runner, where a narrow beam of light shines through the rotating blades of a fan, highlighting Thomson’s tortured hands and Webber’s prone body. Elsewhere his lights gleam from filing cabinets and ventilation ducts, bringing life and mystery to the banality of the realistically designed set.

Choreographically Cockfight is structured around lifts and grapples, circus-like table slides, dramatic leaps and a subtle sense of constrained intimacy which speaks directly to the masculine rituals on show. The movement vocabulary occasionally feels restricted, but this is balanced out by the work’s enthusiasm, which sees the stage showered with paper planes and scattered files throughout. Other images, including haunting blank masks and the beating wings of a Sooty Shearwater created through a standard piece of office equipment, are striking and inventive.

The two performers give it their all – by the time the 70-minute work reaches its tightly knotted finale the pair are sweat-soaked and breathless. Entertainment and artistry are well balanced; this is not a challenging work but it is rigorously crafted.

Lucy Guerin Inc’s Split

Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall

16-26 March

4 stars

Lilian Steiner and Melanie Lane in Split; photo by Gregory Lorenzutti.

Even before the lights dim the performance begins; an insistent beat courtesy of UK composer Scanner. As Lucy Guerin’s latest work unfolds the score ebbs and flows, allowing the sounds of the dancers’ breathing to emerge from the mix; an audible recognition of the centrality of physical movement to this subdued, cerebral yet compelling work.

Two dancers – Lilian Steiner (who is naked throughout) and Melanie Lane (clad in a light blue shift) – enter the performance space, which is outlined by a large rectangle of white tape. Initially they keep close to their original mark as if fearful of venturing out into the unknown. As the dancers venture further into the performance space there’s an almost playful evocation of childhood, youthful joy and lolloping around the space with gusto – until they begin to seal themselves in.

Over time, despite claiming more of the stage, they recreate their own constraints, restricting themselves into smaller and smaller areas; sealing themselves off, turning on one another and themselves in a dance evoking anxiety, concern, and silent, internalised violence.

The precise performances are beautifully synchronised: bodies bob, arms swing, wrists turn together. Floor work features small, precise turns of the head and considered hand gestures. Movements are sharp and focused, whether reclining, half kneeling, walking over one another or climbing one atop the other.

Each alteration of the space, each limiting of capacity, is accompanied by a precise and evocative lighting change; the final scene – the make or break moment – is matched by a plunge into darkness.

Split feels both deeply personal and deeply considered. Though open to many readings, one is that it’s a compelling examination of the pressures placed on women and how such pressures are internalised and absorbed, expressing themselves as self-doubt and insecurity, eating disorders and rage.

Confident and compelling, it’s another fascinating work from one of Melbourne’s leading choreographers.

Nicola Gunn’s Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster

The Coopers Malthouse, Southbank

15-26 March 2017

4 stars

Nicola Gunn in Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster; photo by Gregory Lorenzutti.

Melbourne performance maker Nicola Gunn’s Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster premiered in 2015, and returns for Dance Massive following successful national and international tours.

The work, a dense, dizzying, elliptical and humorous monologue, is inspired by a unique moral conundrum: if, while visiting a foreign country, you went for a run beside a river, how would you react when you encountered a man throwing stones at a nesting duck while his young children watch on?

What are the ethics of intervention in such circumstances? The man appears to be a migrant – perhaps throwing rocks at sitting ducks is acceptable behaviour in his country? And given that you’re currently having an affair with a married man, just how rock-steady is your own sense of moral superiority?

The country in question is Belgium; soon after mentioning this, Gunn’s narrative has jumped tracks to discuss the famous fictional Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, the actor who played him, open heart surgery, and the idea of marionettes replacing actors on stage. And that’s just the first five minutes.

Despite the torrent of words and ideas ricocheting out of Gunn’s mind and into ours, Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster never feels rushed, thanks to Gunn’s skill as a performer and Jo Lloyd’s accompanying choreography.

Gunn is in almost constant motion throughout the piece: crouching, reclining, extending an arm, slowly oscillating her ‘hypnotic legs’ or embracing the audience wholeheartedly. After discussing personal shame her hands adopt a prayer-like pose, folded but rolling forward as she takes short, chopping steps, a stylised version of some solemn religious procession. Touching on the noted animal ethicist Peter Singer her movements take on a hint of the tightrope walker’s fine balance; elsewhere the choreography is less literal, more playful, exaggerated and explosive.

In the work’s final moments, having presented the audience with multiple perspectives on her original conundrum, Gunn ratchets the tone up a notch with a rock-opera finale that’s as glorious as it is absurd – think Rick Dees’ 1974 novelty song ‘Disco Duck’ as reinterpreted by Peter Gabriel during his psychedelic Genesis days, replete with a multi-coloured cloak, theatrical smoke, a thumping Kelly Ryall score and ultraviolet laser lights. Is it self-indulgent? Absolutely – but it’s a deserved indulgence after such a strong performance, and a gloriously surreal ending to a rewarding production that’s as full of ideas as it is surprises.

Nick Power’s Between Tiny Cities រវាងទីក្រុងតូច

Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall

Until 18 March

4 stars

Dancers Erak Mith & Aaron Lim in Between Tiny Cities រវាងទីក្រុងតូច; photo by Bryony Jackson.

From Los Angeles to London, and Darwin to Phnom Penh, dance battles are a common component of b-boy culture. In this latest exploration of the form, choreographed by Sydney-based hip-hop dance artist Nick Power, two men use the rituals, movement styles and language of their shared hip-hop culture to explore points of commonality and difference. The result is an intelligent, expressive and engaging production which gently subverts preconceptions around hip-hop and masculinity, providing an ideal entry point to contemporary dance for those unfamiliar with the genre while also providing much for aficionados to enjoy.

Read: Not lost in translation

In the work’s early stages, the two performers – Aaron Lim (Darwin) and Erak Mith (Phnom Penh) – stand opposite each other, echoing one another’s abrupt movements, encircled by the audience (who stand throughout proceedings). Lim’s gestures are strikingly precise; Mith is more fluid, his slighter body assisting him in the piece’s more acrobatic moments.

The four main elements of b-boying are all present, including swiftly performed power moves – windmills and headspins – and dramatic freezes, but there’s no sense of Power being limited by tradition. As the work progresses the dancers’ bodies, once in vigorous competition, become united, their movements fluid, occasionally even tender. Arms lock together, fingers bloom like rare flowers. Jack Prest’s score is driving but never dominating, and as the lights dim as the piece ends, there’s a strong sense of wanting the work to continue. A rich exploration of the possibilities of hip-hop choreography and an early highlight of Dance Massive.

Victoria Hunt’s Tangi Wai… the cry of water

Meat Market, North Melbourne

Until 18 March

3 ½ stars out of 5

Photo by Bryony Jackson

A powerful sensory experience, Victoria Hunt’s Tangi Wai…the cry of water originally premiered as part of Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art in October 2015. Inspired by the Australian-born Hunt’s Maori heritage, the piece transports its audience into a world of elemental and supernatural forces. The result is hypnotic, imaginative and richly realised, with light, water, sound and movement impressively combined, though as the work builds, there’s also a slight, nagging sense of absence – a lack of physical presence, with the dancers only half-glimpsed for prolonged periods, their movements sometimes frustratingly invisible. Clearly it’s a deliberate choice: Hunt demonstrates total control throughout the piece, so perhaps one should read this absence of ‘dance’ as a deliberate challenge to Western preconceptions of art and entertainment – perhaps even an evocation of the absence of Indigenous cultures in a predominantly white Australia?

Design elements are the real stars of the show – wafts of mist, crackling lines of light, cacophonous and chthonic sounds. Fragmented bodies emerge slowly from the darkness: sometimes angular and almost inhuman in the shadows, at other moments filleted by light so that all we see are hips and legs, like ancient fertility images. A hip thrusts, toes stretch and scrabble at the slippery floor.

These glimpses of movement are isolated; Hunt’s focus is clearly larger than the dance alone. The final image is remarkable: what appears to be a mask or a shield is revealed as a human back – an act of transmogrification that typifies the imagination of this remarkable and challenging work.

Dance Massive

dancemassive.com.au

14–26 March 2017