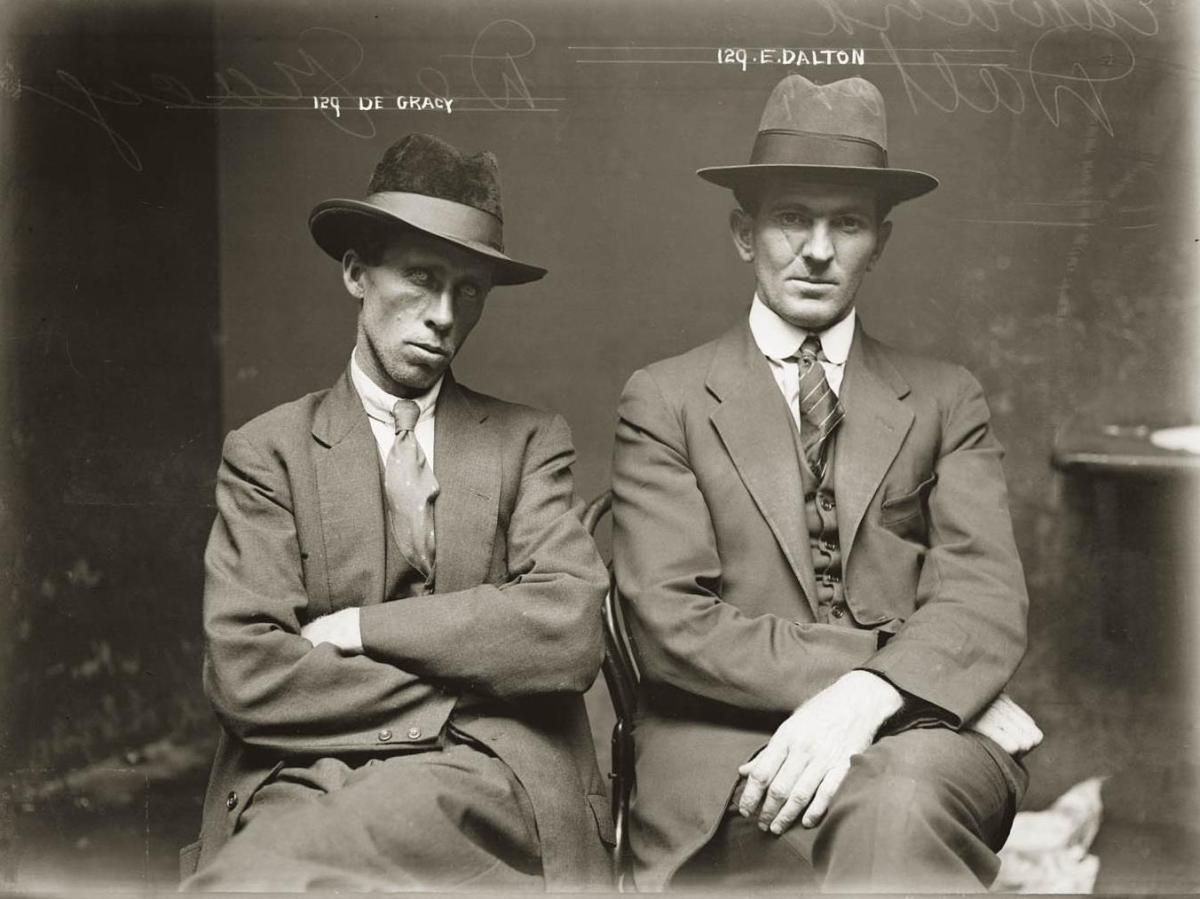

Mug shot of De Gracy (sic) and Edward Dalton. Details unknown. Central Police Station, Sydney, around 1920.

Between 2002 and 2005 Peter Doyle spent hundreds of hours poring through the forensic photographs in the loft of Sydney’s Justice & Police Museum. Taken between 1910 and 1960, the photographs are a combination of mug shots, streetscapes and crime scenes. Exhaustively curated by Doyle, the subsequent exhibition is small yet arresting.

Oft walked streets are shown bare; not a body, living or dead, to be seen. Square-chinned detectives wear coats long enough to skim the cuff of their pants; they mill around the home and shop fronts of Broadway, Chippendale, Waterloo. One stares up at us from the bottom of Argyle Steps–be it Huston of Hammett, you couldn’t ask for a better Sam Spade. Bodies, crystallised in black and white, lay crumpled on the floor. Detail-filled interiors–some dusty, some well-kept, some left in a violent shambles–bring us through the terrace threshold at the point of tragedy. Cross-dressing confidence men smile to the camera in their peculiarly casual mug shots. What’s going on here? You’re invited to pick away at the particulars–play detective.

This isn’t the first time City of Shadows has been exhibited; it ran back in 2006. Calls trickled in and the utterances of memories began to paint a more complete picture. Prior to the community getting involved many of the images gave away no more than what was left on the glass plate negatives. The re-opened exhibition explores how some cases have been cracked.

A new short film, screening in the second room, examines how this coterie of local informants helped solve the mystery of some of the exhibition’s most startling scenes. The blog is another new addition, satisfying the urge of the visitor-come-investigator biting at the bit to dig deeper. I turn into the third room: Unidentified corpse, partly obscured, lying in a loading dock. The curled hands, the crumple in the pant leg, the wooden pipe in the gutter – all point to a bloke snuffed out on his smoko. When I get home I turn to the blog. I want a closer look at the evidence.

And yet, this isn’t solely an exhibition about crime. City of Shadows is a glimpse into the milieu of Sydneysiders past. Second room, right wall––nothing but mug shots. A motley mob of thieves, bigamists, larcenists, madams, illywhackers, cocaine lovers, wife killers, vagrants and owners of houses ‘frequented by reputed thieves’ occupy the space. Some stare out at you, some hang their heads, some smile. Dubbed the ‘Special Photographs’ these aren’t the front-and-profile processing shots we’re used to. Taken between 1910 and 1930, Doyle suggests ‘the subjects of the Special Photographs seem to have been allowed – perhaps invited – to position and compose themselves for the camera as they liked. Their photographic identity thus seems constructed out of a potent alchemy of inborn disposition, personal history, learned habits and idiosyncrasies’ compared to the subjects of prison mug shots. Looking at a photo of one Adolf Gustave Beutler, whose picture is inscribed with the words ‘wilful and obscene exposure’, I can’t help but think of my grandmother’s beloved idiom for a well-dressed man with a sinister streak: Beutler is, as many of the fellows are, as flash as a rat with a gold tooth.

And here I am, looking at a female corpse splayed out on a single bed, blood congealed on a pillow laying at her side (notes in the archives suggest that detectives moved the pillow from her face and pulled up the blinds to let the light in to capture the shot) thinking of my nan. It was around 1942 when this unidentified woman with the American flag above her bed and the copy of True Confessions, a bit of American crime pulp, thrown on her leather armchair was killed; shot as she lay. Nan’s age matched the year. What was Sydney like back then? Back when women were shot through the heart in their beds with their stockings on. When boys dressed as girls trying to coax US servicemen out of a few dollars. When criminal dandies embraced like mates posing at a party for their mug shot.

Sometimes it feels as if Sydney is a city too young to have an interest in its history. Sometimes it feels the official history we’re given doesn’t quite fit the vibe of the place. There’s something rough about this town. You can’t shake it. We don’t want to. The Razor Gang, Kings Cross, Tilly Devine, Abe Saffron – this stuff, sordid as it is, feels real.

There’s an old Australian saying ‘He’s got the moz on him,’ meaning someone’s been struck by an evil influence. It’s an abbreviated form of mozzle, a borrowing from the Hebrew mazzle, meaning star or luck. Sydney between 1912 and 1948 was a city of battlers, criminals, and the poor folks who lay somewhere in-between: those who simply had the moz on them. They came from all over to this big old port to start lives afresh. Sometimes that meant running away. Occasionally it meant turning to petty crime if you wanted the money and the personal security to get along. Often it meant isolation in a community that wasn’t quite your own.

Perhaps City of Shadows shows we’re a city defined by our criminality; and not necessarily the convict kind. At the very least it intrigues us. How else to account for the exhibition’s response? Second run. Third year. No hint of an end date. City of Shadows puts the blood back into our streets. Streets, we could argue, now rendered impotent by government wowsers––lock outs, one-punch laws, the Saturday-night police presence. But we’re also a city defined by the down-and-out – the homeless, the poor, the battered wives – by the opportunities we collectively fail to afford them, and by the secret struggles going on behind closed doors. City of Shadows holds up a mirror to who we were back then. It tells us how much things have changed and reminds us of what hasn’t.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

City of Shadows: Inner City Crime & Mayhem 1912-1948

Justice and Police Museum

Sydney Living Museums