Even while they were still tuning up, it gave a greater sense of importance to the event that would draw the ACO into more Romantic waters than it usually explores.

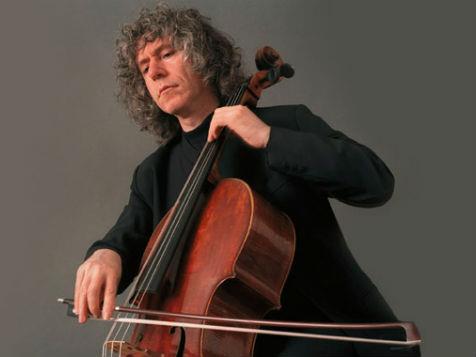

The interest in the first half of the concert was primarily in the soloist. British cellist Stephen Isserlis is always a welcome visitor to Australia, and is instantly recognisable for his (now greying) mop of curls and appearance of contained energy. Both on and off the concert stage Isserlis has revealed himself as a thoughtful and feeling musician, attributes that are evident in his playing.

The ACO introduced the Dvorak Cello Concerto with quite mournful horns, echoed by other instruments until the sound swelled to a climax. There was more to come as the solo horn carried the theme, and the strings provided the harmony. A dance-like motif made the performance seem rather like an overture.

Director and violinist Richard Tognetti kept a measured pace, which allowed for a smooth entry by the solo cello. (It is one of Tognetti’s great attributes that, as a soloist himself, he understands how to prepare the way for a solo instrument).

Isserlis appeared absorbed in the music, playing with great beauty and attention to the resonance of each note. His skilful bowing was worthy of attention even when the winds appeared to have the melody (although that section of the orchestra deserves praise for its development of the theme). The end of Isserlis’s solo part at this point was unutterably beautiful.

Fine work from the brass brought the movement to a close. And then the unthinkable happened. Despite at least four warnings before the concert began, a mobile phone went off. It was very near the front, almost literally at the soloist’s feet. Isserlis looked shocked, of course, and then quite distressed. It was some time before Tognetti moved to begin the second movement.

The winds opened this movement, and continued as a foil for the cello, in a piece of unrestrained emotion. The program notes referred to the well-known story that the work was overshadowed by news of the illness, and later, death of Dvorak’s beloved sister-in-law Josefina Kaunitzova. The second movement even incorporates one of her favourite songs.

In the middle section, it is left to the horns and lower strings to sustain the mod – although an emotive solo by Isserlis had the rest of the hall completely hushed. Lighter arpeggios to end showed the beauty of the instrument, even when played softly. By contrast, the final movement was a dramatic, at times march-like, piece, the first hint of the folk rhythms never far from Dvorak’s music.

Isserlis continued to be engrossed in the music and Tognetti controlled the dynamics so that the solo instrument was always important, no matter what else was happening. Changes from minor to major keys were notable, and at times the sound was almost Wagnerian, at other times subdued. But the applause was consistently loud, and Isserlis was not allowed to leave without playing an encore.

After interval the ACO had its time in the spotlight with its performance of Brahms’s Symphony No.4. It was the ideal vehicle for the orchestra to demonstrate its credentials in music of a later period than its usual Baroque and Classical offerings. From the outset, Tognetti and the ACO owned the work.

The lyrical, melodic beginning soon became a sweeping sound in which the entire orchestra was caught up. It suited the ACO’s strengths – including the full string sound, and Tognetti’s solo role – but also noteworthy were the winds accompanied by pizzicato strings. A series of emphatic notes heralded an impressive ending to the first movement.

Horns and winds introduced a sombre sound to the second movement, Andante moderato. This developed into a rich, warm sound, especially with Tognetti’s solos, the horns and other brass lending depth. In contrast the Allegro giocoso was as joyful as it promised (a triangle lending a sparkling effect), with an evident bow to the scherzo. The final movement brought an Allegro of a different kind, featuring the brass and reiterations of a dance-like theme.

These variations and a great swell of sound made for both an impressive ending to the symphony, and a triumphant rounding-off of a very enjoyable concert, thanks to Tognetti, Isserlis and the ACO.

Rating: 4 1/2 stars out of 5

Mon 21 Oct at 8pm

Arts Centre Melbourne

NB: On tour until 29 October

Program

Dvorak Cello Concerto

Brahms Symphony No.4

Artists

Australian Chamber Orchestra

Steven Isserlis Cello

Richard Tognetti Director and Violin

Image: Melbourne Festival Website