An essential problem for settler nature writers of so-called Australia is English. How do you suitably wield a language to describe a place when that language evolved to describe a different place entirely?

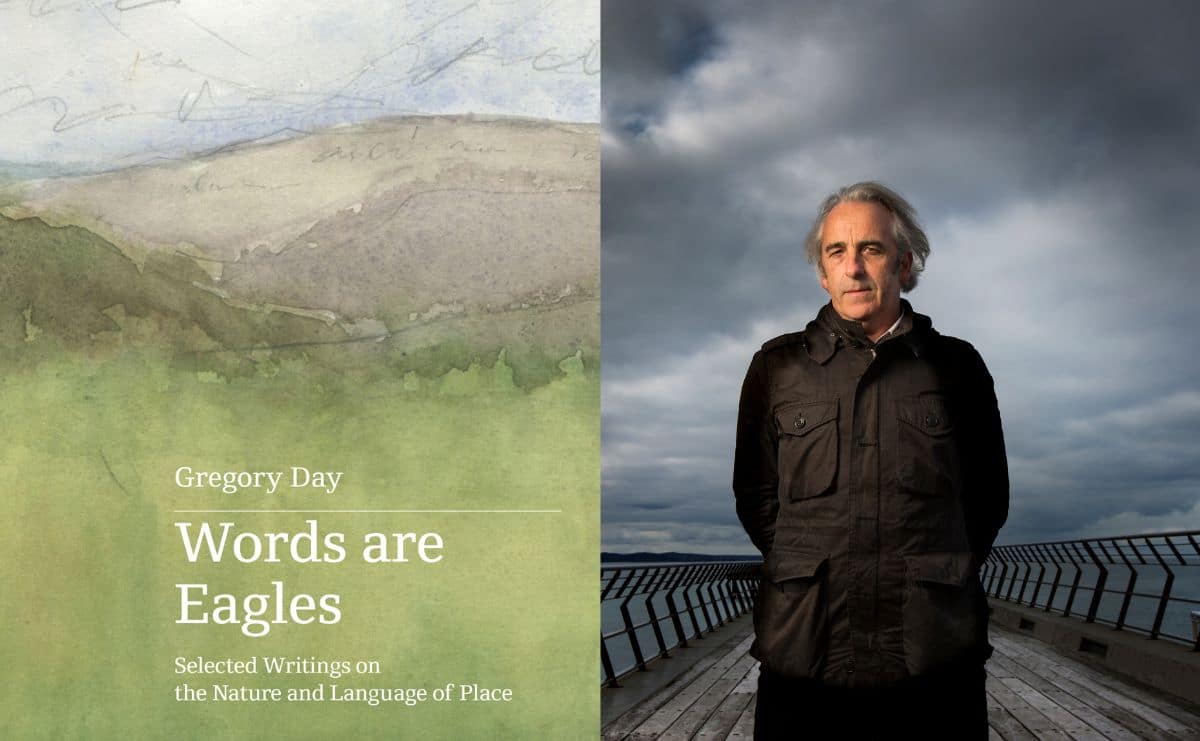

Gregory Day’s essay collection, Words are Eagles, poetically and reflectively articulates this problem, and provides creative and interrogative responses to it. The reflections are clearly situated in Day’s own experience, predominantly on the coastal areas of Wadawurrung Country, as someone with Irish and Italian heritage, and informed by his own family history surrounding the sea as a healing place for grief.

Nature writing has an ethical purpose. The reality of climate change, environmental degradation, and the dangers humans have placed on animal life in our ‘careless dominion’ makes connecting to nature a vital practice. The consequence of disconnection is memorably captured by Day’s experience of seeing a platypus garrotted by a newspaper rubber band along the Yarra River. This scene appears in the collection’s striking afterword, ‘What Jesus Wrote on the Earth’, whereby animal suffering takes on a spiritual urgency.

Day also highlights the ethics of nature writing in terms of decolonisation, given the inextricable connection between landscape and language. In the essay, ‘One True Note?’, Day describes a scene in Alan Garner’s novel, Sandloper, where settler understandings of written language as benign and useful are challenged by Nullamboin, a fictional Aboriginal elder. To Nullamboin, the written word is a ‘superficial way of transmitting culture’, allowing people to gain knowledge without the requisite support or experience to use the knowledge well.

As Day explains [emphasis original], ‘if knowledge was something to be attained through certain careful techniques, like nectar from a comb, if it was to be ritually developed like the shapeliness of maturing skin or the muscle of a growing arm, then time and experience, events in the landscape, were the true etymology of the language-creature that served as the carrier of this knowledge.’

In this way, language and landscape are not separate, ‘the descriptor and the object of description in any given phrase, lyric or sentence, enact a two-way exchange, as in the umbilical bond between mother and child, or the sensory communion between landscape and the dweller within it.’ Settler attempts to describe nature, especially as they come to know it better, can lead to ‘disorientation’ – the English words aren’t quite right because they don’t come from the landscape itself.

Read: Theatre review: Peer Gynt

This is a thought-provoking collection that will be arresting to nature-lovers who find themselves struggling to describe the awe of the world around them. Day offers a blueprint of what a settler reckoning to their own naïve position in relation to landscape and language might look like.

Part three of the collection, primarily featuring literary critical writing, may interest general nature lovers less. Though, through the concept of ‘wreading’ (the way one’s reading and writing may merge as part of an iterative process) Day argues for the importance of literature as a cultural inheritance, helping each of us to approximate the nuances of the world with increasing accuracy and care.

Words are Eagles: Selected Writing on the Nature & Language of Place, Gregory Day

Publisher: Upswell Publishing

ISBN: 978045076387

Pages: 288pp

Publication: July 2022

RRP: $29.99